On Instagram, creator Mrs. Frazzled can get more than a million viewers for her goofy videos “parenting” misbehaving adults. One recent hit showed bartenders how to talk to drunk customers like they’re in kindergarten. But lately, she’s been frazzled by something else: Whenever she posts about the election, she feels as if her audience disappears.

Mrs. Frazzled, whose real name is Arielle Fodor, let me inside her Instagram account to investigate. I found that whenever she mentioned anything related to politics over the last six months, the size of her audience declined about 40 percent compared with her nonpolitical posts.

It appears she can’t even say “vote.” When she used the word in a caption across 11 posts, her average audience was 63 percent smaller. “It is very disempowering,” Fodor says.

If you’ve suspected that you’re yelling into a void about the election on Instagram, Facebook or Threads, it might not be your imagination, either. Downplaying politics is a business and political strategy for Meta, the social media giant. And users just have to accept it.

Consider a wider study by the advocacy group Accountable Tech, which quantified the audience drop for five prominent liberal Instagram accounts, including the Human Rights Campaign and Feminist, that post almost entirely about politics. Over 10 weeks this spring, their average audiences fell 65 percent.

And it’s not just Instagram: Only one of six social media giants would tell The Washington Post whether you can use the word “vote” without having a post suppressed.

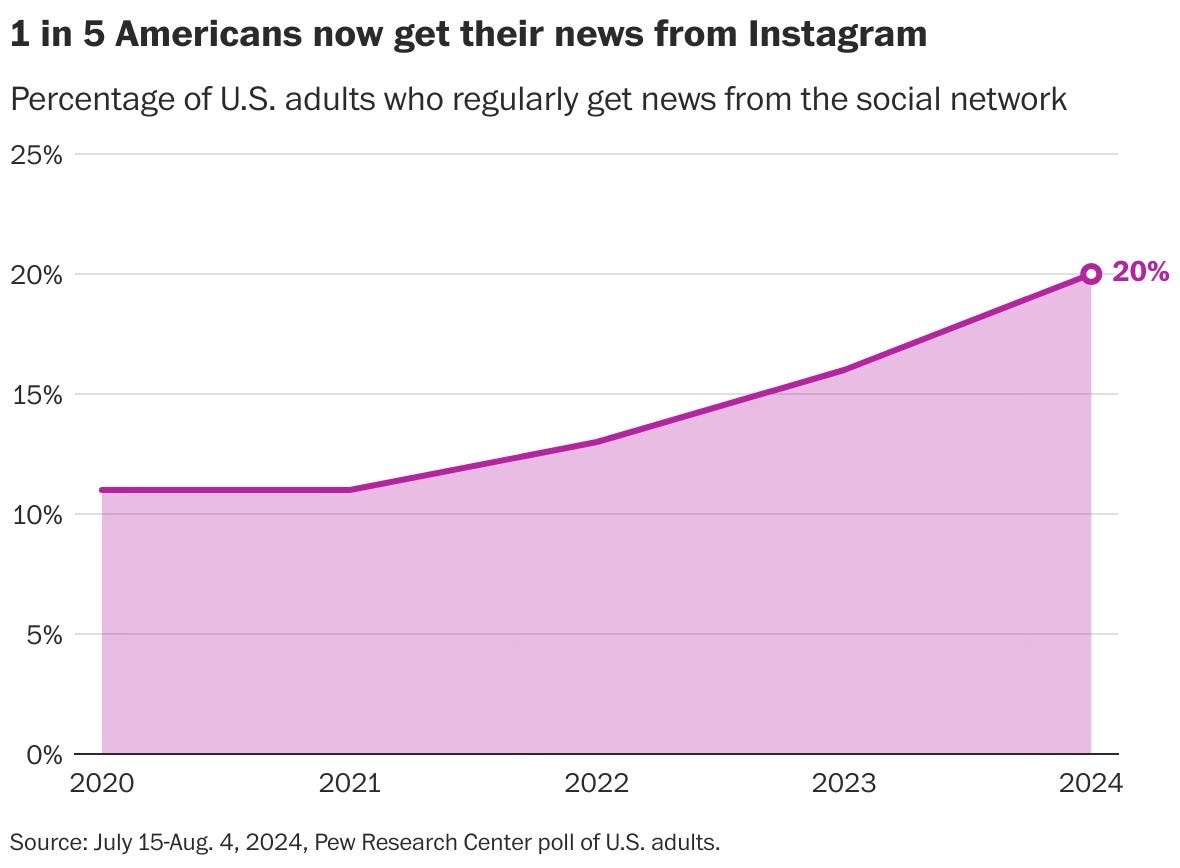

It matters because social media has a profound impact on how people see themselves, their communities and the world. One in five American adults regularly get their news from Instagram — more than TikTok, X or Reddit — according to the Pew Research Center.

It could leave swaths of Americans wondering why we aren’t hearing as much about the election. And less likely to vote, too.

Meta doesn’t deny that it’s suppressing politics and social issues. But as my deep dive into Mrs. Frazzled’s Instagram account shows, it has left users in the lurch — and won’t give straight answers about when, and how, it reduces the volume on what we have to say.

During the dark days of covid lockdowns, Fodor started posting about virtual teaching, on TikTok and, eventually, Instagram. Over time, she developed the Mrs. Frazzled persona, which often employs her high-pitched teacher voice for humor. She got the most engagement from audiences on Instagram, where she has 377,000 followers.

Today, Fodor is a 32-year-old mom in graduate school who earns money as an online creator. As the 2024 election approached, her interests increasingly turned to politics and social issues. These topics accounted for about a third of her posts for the six months that ended in September. Some were about abortion rights or critical of Donald Trump, while others were more nonpartisan and educational, such as an explanation of ranked-choice voting. (Fodor says she hasn’t taken money from either presidential campaign.)

She noticed right away that her election work wasn’t taking off. “It’s a huge barrier when we have the interconnectedness of social media at our fingertips and we cannot even share any messages about the election process,” Fodor says.

Her frustration is a product of a change of heart by Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg. In 2021, he began pulling back on political content on Facebook, after years of being accused by Republicans of favoring Democrats.

The hatchet fell on Instagram this year. In a February blog post, Meta said it would no longer “proactively recommend content about politics,” including topics “potentially related to things like laws, elections, or social topics.”

Translation: Meta tightened the reins over what to put in your feed and Explore tab, specifically from accounts you don’t already follow.

As part of the shift, Instagram also opted everyone into a new setting to have it recommend less political content from accounts you don’t follow. It did not alert users to this inside the Instagram app. (If you don’t want a sanitized feed on Instagram, Facebook or Threads, I’ve got instructions for how to change your settings below.)

This is not exactly “censorship” — anyone can still post about politics, and people who already follow you can still see it. That’s how Taylor Swift reached her 283 million followers with an endorsement of Kamala Harris.

But it is a form of what creators and politicians have long called “shadowbanning”: reducing the reach of certain kinds of content without being transparent about when it’s happening. Political campaigns, too, have been scrambling to find alternative ways to break through.

Why is Meta doing this? “As we’ve said for years, people have told us they want to see less politics overall while still being able to engage with political content on our platforms if they want to — and that’s exactly what we’ve been doing,” Meta spokesman Corey Chambliss said in a statement.

What short memories they have at Meta HQ. I was there in 2011 when Zuckerberg live-streamed an interview with President Barack Obama that explored how social media would contribute to democracy. “What Facebook allows us to do is make sure this isn’t just a one-way conversation,” Obama said during the chat.

Meta says it continues to run a program to point users to official information about registering and voting. But it thinks the majority of Americans want less politics on social media. I agree most of us don’t want political vitriol or Russian disinformation — but that’s not the same as respectful conversation. And Meta has complete control over three of the most widely used tools for self-expression.

In the spring, Fodor joined other creators in a letter to Meta, saying the company had abandoned its responsibility “to be an open and safe space for dialogue, conversation, and discussion.”

What Fodor finds particularly disempowering is that she doesn’t know when, or how, her work crosses the line.

Creators mostly have to guess, leaving them in a state of what you might call algorithmic anxiety. “It makes people more distrustful of these social media platforms,” she says.

Instagram never flagged any of her individual posts as being too political to recommend.

It is possible that Fodor’s political stuff isn’t popular because it isn’t as good. But the data suggests that isn’t likely. Looking at the details of her audience reports, I could see that her political content was, on average, seen by significantly fewer people who aren’t her followers — suggesting that Instagram was putting a thumb on the scale.

And when people did see Fodor’s political posts, they were nearly 50 times as likely to individually share them by pressing the paper airplane icon in the Instagram app.

Zuckerberg has a First Amendment right to make decisions about what to promote on his platforms. But his users deserve transparency about what topics are limited — and how Instagram determines what’s over the line. Meta declined to comment on the Mrs. Frazzled account, saying fluctuations in engagement are common and can ebb and flow for reasons that have nothing to do with its policy changes.

I sent Meta questions about how it determines what to reduce. It wouldn’t detail what it means by “political and social issues” beyond content potentially related to “things like laws, elections, or social topics.”

How do its automated systems make these calls? Would mentioning Taylor Swift count as political? What about coconuts? Can it make a distinction between voting information and partisan bickering?

I also asked Meta for a list of forbidden keywords, after I noticed that Fodor’s use of “vote” in captions correlated to a steep audience drop. Meta wouldn’t share that, either, saying thousands of factors affect how content is ranked and recommended.

Meta put a slightly finer point on “social topics” in a statement to The Post earlier in the year, defining it as “content that identifies a problem that impacts people and is caused by the action or inaction of others, which can include issues like international relations or crime.”

But that definition could rule out wide swaths of the lived human experience, including people talking about their family in the Middle East or simply being gay or trans.

“These are such integral parts of some people’s identities and livelihoods — Meta’s gone so far as to limit their capability to talk about who they are and what they care about,” says Zach Praiss, Accountable Tech’s campaigns director, who led the organization’s research.

Fodor says she’s glad to know she wasn’t imagining the problem. “To see it laid out with data is so affirming,” she says.

So what does she do now? She’ll keep on posting, she says: “I’ll do a little yelling into the void.”

Unfortunately for our democracy, she doesn’t have a lot of other choices.

Andrea Jimenez contributed to this report.