There is one world in common for those who are awake, but when men are asleep each turns away into a world of his own.

- Heraclitus, 2500 years agoWe’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.

- Unknown official in the George W. Bush administration, 20 years ago

Do you feel that people you love and respect are going insane? That formerly serious thinkers or commentators are increasingly unhinged, willing to subscribe to wild speculations or even conspiracy theories? Do you feel that, even if there’s some blame to go around, it’s the people on the other side of the aisle who have truly lost their minds? Do you wonder how they can possibly be so blind? Do you feel bewildered by how absurd everything has gotten? Do many of your compatriots seem in some sense unintelligible to you? Do you still consider them your compatriots?

If you feel this way, you are not alone.

We have come a long way from the optimism of the 1990s and 2000s about how the Internet would usher in a new golden era, expanding the domain of the information society to the whole world, with democracy sure to follow. Now we hear that the Internet foments misinformation and erodes democracy. Yet as dire as these warnings are, they are usually followed with suggestions that with more scrutiny on tech CEOs, more aggressive content moderation, and more fact-checking, Americans might yet return to accepting the same model of reality. Last year, a New York Times article titled “How the Biden Administration Can Help Solve Our Reality Crisis” suggested creating a federal “reality czar.”

This is a fantasy. The breakup of consensus reality — a shared sense of facts, expectations, and concepts about the world — predates the rise of social media and is driven by much deeper economic and technological currents.

Postwar Americans enjoyed a world where the existence of an objective, knowable reality just seemed like common sense, where alternate facts belonged only to fringe realms of the deluded or deluding. But a shared sense of reality is not natural. It is the product of social institutions that were once so powerful they could hold together a shared picture of the world, but are now well along a path of decline. In the hope of maintaining their power, some have even begun to abandon the project of objectivity altogether.

Attempts to restore consensus reality by force — the current implicit project of the establishment — are doomed to failure. The only question now is how we will adapt our institutions to a life together where a shared picture of the world has been shattered.

This series aims to trace the forces that broke consensus reality. More than a history of the rise and fall of facts, these essays attempt to show a technological reordering of social reality unlike any before encountered, and an accompanying civilizational shift not seen in five hundred years. ♣

Read the list of statements below.

For each statement, write down whether it is true or false, and whether the issue is very important or not that important.

Pick the friend whose political beliefs are most different from yours, and to whom you are still willing to speak. Ask your friend to complete the questionnaire too. Explain to this friend why his or her answers are insane.

On the recent twentieth anniversary of 9/11, I reflected on how I would tell my children about that day when they are older. The fact of the attacks, the motivations of the hijackers, how the United States responded, what it felt like: all of these seemed explicable. What I realized I had no idea how to convey was how important television was to the whole experience.

Everyone talks about television when remembering that day. For most Americans, “where you were on 9/11” is mostly the story of how one came to find oneself watching it all unfold on TV. News anchors Dan Rather, Peter Jennings, and Tom Brokaw, broadcasting without ad breaks, held the nation in their thrall for days, probably for the last time. It is not uncommon for survivors of the attacks to mention in interviews or recollections that they did not know what was going on because they did not view it on TV.

If you ask Americans when was the last time they recall feeling truly united as a country, people over the age of thirty will almost certainly point to the aftermath of 9/11. However briefly, everyone was united in grief and anger, and a palpable sense of social solidarity pervaded our communities.

Today, just about the only thing everyone agrees on is how divided we are. On issue after issue of vital public importance, people feel that those on the other side are not merely wrong but crazy — crazy to believe what they do about voter ID, Russiagate, critical race theory, pronouns and gender affirmation, take your pick. Americans have always been divided on important issues, but this level of pulling-your-hair-out, how-can-you-possibly-believe-that division feels like something else.

It is hard to imagine how we would have experienced 9/11 in the era of Facebook and Twitter, but the pandemic provides a suggestive example. Just as in 2001, in 2020 we faced a powerful external threat and had a government willing to meet it. But instead of unity, American society has experienced tremendous fragmentation throughout the pandemic. Beginning with whether banning foreign travel or using the label “Wuhan virus” was racist, to later mask mandates, school closures, lockdowns, and vaccine requirements, we googled, shared, liked, and blocked our way apart. Nobody was tuning in to the same broadcast anymore.

Of course, we have heard no end of laments for the loss of the TV era’s unity. We hear that online life has fragmented our “information ecosystem,” that this breakup has been accelerated by social division, and vice versa. We hear that alienation drives young men to become radicalized on Gab and 4chan. We hear that people who feel that society has left them behind find consolation in QAnon or in anti-vax Facebook groups. We hear about the alone-togetherness of this all.

What we haven’t figured out how to make sense of yet is the fun that many Americans act like they’re having with the national fracture.

Take a moment to reflect on the feeling you get when you see a headline, factoid, or meme that is so perfect, that so neatly addresses some burning controversy or narrative, that you feel compelled to share it. If it seems too good to be true, maybe you’ll pull up Snopes and check it first. But you probably won’t. And even if you do, how much will it really help? Everyone else will spread it anyway. Whether you retweet it or just email it to a friend, the end effect on your network of like-minded contacts — on who believes what — will be the same.

“Confirmation bias” names the idea that people are more likely to believe things that confirm what they already believe. But it does not explain the emotional relish we feel, the sheer delight when something in line with our deepest feelings about the state of the world, something so perfect, comes before us. Those feelings have a lot in common with how we feel when our sports team scores a point or when a dice roll goes our way in a board game.

The unity we felt watching the news unfold on TV gave way to the division we feel watching events unfold online. We all know that social media has played a part in this. But we should not overestimate its impact, because the story is much bigger. It is a story about the shifting foundations of reality itself — a story in which you and I are playing along.

Hello again. I hope you and your friend are still on speaking terms after our fun collaborative activity. Now let’s try something completely different. Follow me, if you will, into dreamland.

Last week, I saw an ad for a movie in the newspaper, with an old clock in the background. But something was funny about it. The numbers were off — 2, 0, 2, 7….

Could this be a phone number? I tried dialing the first ten numbers, and got an automated message of a woman’s voice in a nebulous accent reading another series of numbers. I have been pulling at the thread ever since.

I did some digging and found out that I’ve stumbled on a kind of game: an alternate reality game. I’m guessing you may not have heard of them?

Alternate reality games are a lot like reading Agatha Christie or Sue Grafton or watching Sherlock. There is something deeply satisfying about unraveling a mystery story when we’re taken in by it. No one has really been murdered, but we still feel suspense until the puzzle is solved.

A good mystery writer will hide the clues in plain sight. She doesn’t have to do that. She could just describe how the detective solves the case. But she does it because she knows that we want to see if we can figure it out ourselves!

Now what if you could do more than just follow along with the story? What if you could actually be the detective? Say you notice a clue and you figure out what it means, and it tells you to look for a hidden message in a classified ad in tomorrow’s newspaper. The message tells you to go to a local bakery tomorrow at noon to find another clue.

That’s what happens in an alternate reality game. It’s a story that you play along with in the real world. It’s like an elaborate scavenger hunt, on the Internet and in real life, with millions of other people all over the world playing along too.

Speaking of which, I have a hunch what the numbers from the lady on the phone mean, but I can’t say anything else on an open channel. If you want to help us solve the puzzle, our Signal chat link is ⬛⬛⬛⬛⬛.

During the Trump era, as a wider swath of people began to pay attention to the online right, a group of game designers noticed disturbing parallels between QAnon, with its endlessly complex conspiracy theories, and their own game creations. Most notably, in the summer of 2020, Adrian Hon, designer of the game Perplex City, wrote a widely shared Twitter thread and blog post drawing parallels between QAnon and alternate reality games.

Theory: QAnon is popular partly because the act of “researching” it through obscure forums and videos and blog posts, though more time-consuming than watching TV, is actually more enjoyable because it’s an active process.

— Adrian Hon (@adrianhon) July 9, 2020

Game-like, even; or ARG-like, certainly.

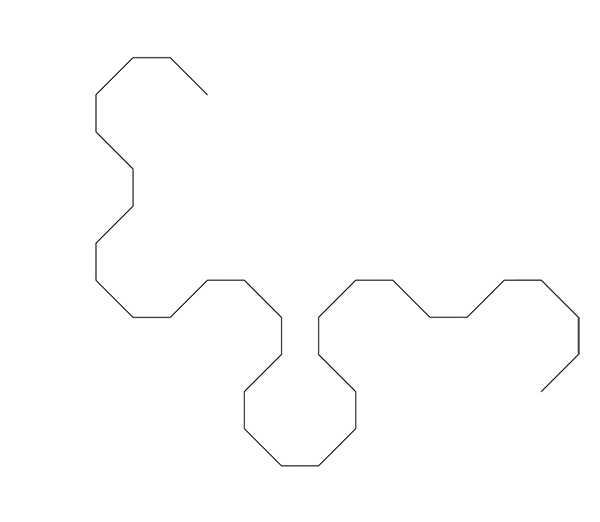

An alternate reality game begins when people notice “rabbit holes” — little details they happen across in the course of everyday life that don’t make sense, that seem like clues. Consider the game Why So Serious?, which was actually a marketing campaign for the 2008 Batman movie The Dark Knight. The game started when some fans at a comic book convention found dollar bills with the words “why so serious?,” and George Washington defaced to look like the Joker. Googling the phrase led to a website … which directed players to show up at a certain spot at a certain time … where a skywriting plane appeared and wrote out a phone number … which led to more clues. Eventually you found out that there was a war going on between the Joker’s criminal gang and the Gotham Police.

The “game masters” don’t necessarily write out the whole story in advance. They might make up some parts of it as they go, creating clues in response to what players are doing. Some games offer prizes, like coordinates to a secret party. But really, the reward is just the satisfaction of solving the mystery.

The structural similarities between all this and QAnon, the game designers thought, were remarkable. In QAnon, too, the rabbit holes can be anywhere: YouTube videos, believers carrying signs at Trump rallies with phrases only other followers would recognize, or enigmatic posts on online message boards. QAnon, of course, also has a game master: Q, the unidentified person behind the curtain. Although he or she has lately been silent, Q used to send regular messages, which pointed to leaked emails, obscure news stories, and numerological puzzles.

Like in QAnon, this blending of online and offline is typical for ARGs. Players navigate a thicket of websites, email accounts, even real phone numbers or voicemail accounts whose passwords you have to figure out. The game masters might send you an email from a character, leak a (fake) classified document on an obscure website, or send you to a real-world dead drop to find a USB drive. At one point in the Batman game, players were directed to a specific bakery, where they could give a name from the game and pick up a real cake with a real phone buried inside.

With both QAnon and alternate reality games, it can be hard to tell what is and isn’t “real.” Of course, QAnon followers think that their world is the real world, whereas ARG players know they are in a game. That’s an important difference. But the point of an alternate reality game is also to blur the boundaries of the game. In fact, many use a “this is not a game” conceit, intentionally obscuring what is real and what are made-up parts of the game in order to create a fully immersive experience.

Unlike role-playing games, in an alternate reality game you play as yourself. Part of what’s so much fun is the community that forms among players, mostly online. For devoted players, status accrues to finding clues and providing compelling interpretations, while others can casually follow along with the story as the community reveals it. It is this collaboration — a kind of social sense-making — that builds the alternate reality in the minds of players.

Likewise, once you get interested in QAnon, there is a rich community built through video channels, discussion forums, and Facebook groups. Late-night chats and brainstorming sessions create an atmosphere of camaraderie. Followers make videos and posts that provide compelling interpretations of clues, aggregate the best ideas from the message boards, and simply entertain others playing in the same sandbox. Successful content creators gain social status and make money from their work.

Most of all, QAnon followers find deep personal satisfaction, achievement, and meaning in the work they are doing to trace the strings to the world’s puppeteers. As the journalist Anne Helen Peterson wrote on Twitter: “Was interviewing a QAnon guy the other day who told me just how deeply pleasurable it is for him to analyze/write his ‘stories’ after his kids go to sleep.” That thrill is not unlike what you feel when you play an alternate reality game.

Maybe this idea that QAnon is like an alternate reality game was just a wild theory too. ARG designers and players may be prone to overestimate the importance of parallels, seeing clues where there are none. Or maybe it was prophetic, considering the role that QAnon adherents would play in the U.S. Capitol attack just a few months after this idea garnered widespread attention. Indeed, there is a case — and I am going to make it here — that the parallel can be fruitfully extended much farther.

Adrian Hon points in the right direction:

I don’t mean to say QAnon is an ARG or its creators even know what ARGs are. This is more about convergent evolution, a consequence of what the internet is and allows.

In other words, the similarities between QAnon and alternate reality games do not owe to something uniquely insane about Q followers. Rather, Hon says, both are outgrowths of the same structural features of online life.

Hon writes that in alternate reality games, “if speculation is repeated enough times, if it’s finessed enough, it can harden into accepted fact.” And Michael Andersen, a writer who has dissected ARGs since the aughts, describes the appeal of seeing the finished game this way: “All of the assumptions and logical leaps have been wrapped up and packaged for you, tied up with a nice little bow. Everything makes sense, and you can see how it all flows together.”

Does this sound familiar? If you had encountered out of context the paragraph you just read, what would you think it was about? Widely held beliefs on Russiagate, perhaps? On the origins of the coronavirus? The 2020 election results? Covid hysteria?

Okay, time for another quiz. Read the list of statements below:

Each of these statements is based on information that has been reported as true by credible mainstream outlets (MIT Media Lab, NBC News, Newsweek, The New Yorker).

Which statement feels most telling — like it speaks to a much bigger story that demands further investigation? Pick one and do the research.

In October 1796, a report appeared in Sylph magazine that sounds peculiar to us today:

Women, of every age, of every condition, contract and retain a taste for novels…. The depravity is universal…. I have actually seen mothers, in miserable garrets, crying for the imaginary distress of an heroine, while their children were crying for bread: and the mistress of a family losing hours over a novel in the parlour, while her maids, in emulation of the example, were similarly employed in the kitchen…. with a dishclout in one hand, and a novel in the other, sobbing o’er the sorrows of Julia, or a Jemima.

Though this may seem silly now, there is reason to think that the eighteenth-century British moralists who panicked over the spread of a new medium were not entirely wrong. Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Voltaire’s Candide, Rousseau’s Emile, and Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, exemplars of the new modern literary form known as the novel, were more than just great works of art — they were new ways of experiencing reality. As literary critic William Deresiewicz has written, novels helped to forge the modern consciousness. They are “exceptionally good at representing subjectivity, at making us feel what it’s like to inhabit a character’s mind.”

Perhaps even revolution was the result. Russian revolutionary activity, in particular, was inextricably tied up with novels. Lenin wrote about Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s novel What Is to Be Done? that “before I came to know the works of Marx … only Chernyshevsky wielded a dominating influence over me, and it all began with What Is to Be Done?,” and that “under its influence hundreds of people became revolutionaries.” He later borrowed the novel’s title for his own 1902 revolutionary tract.

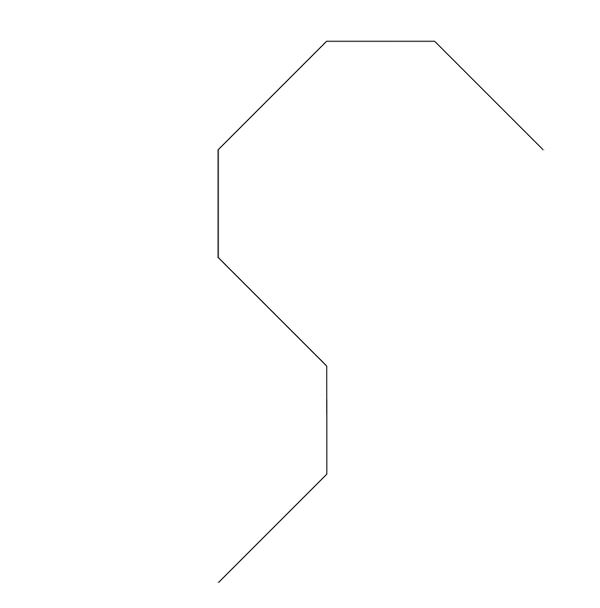

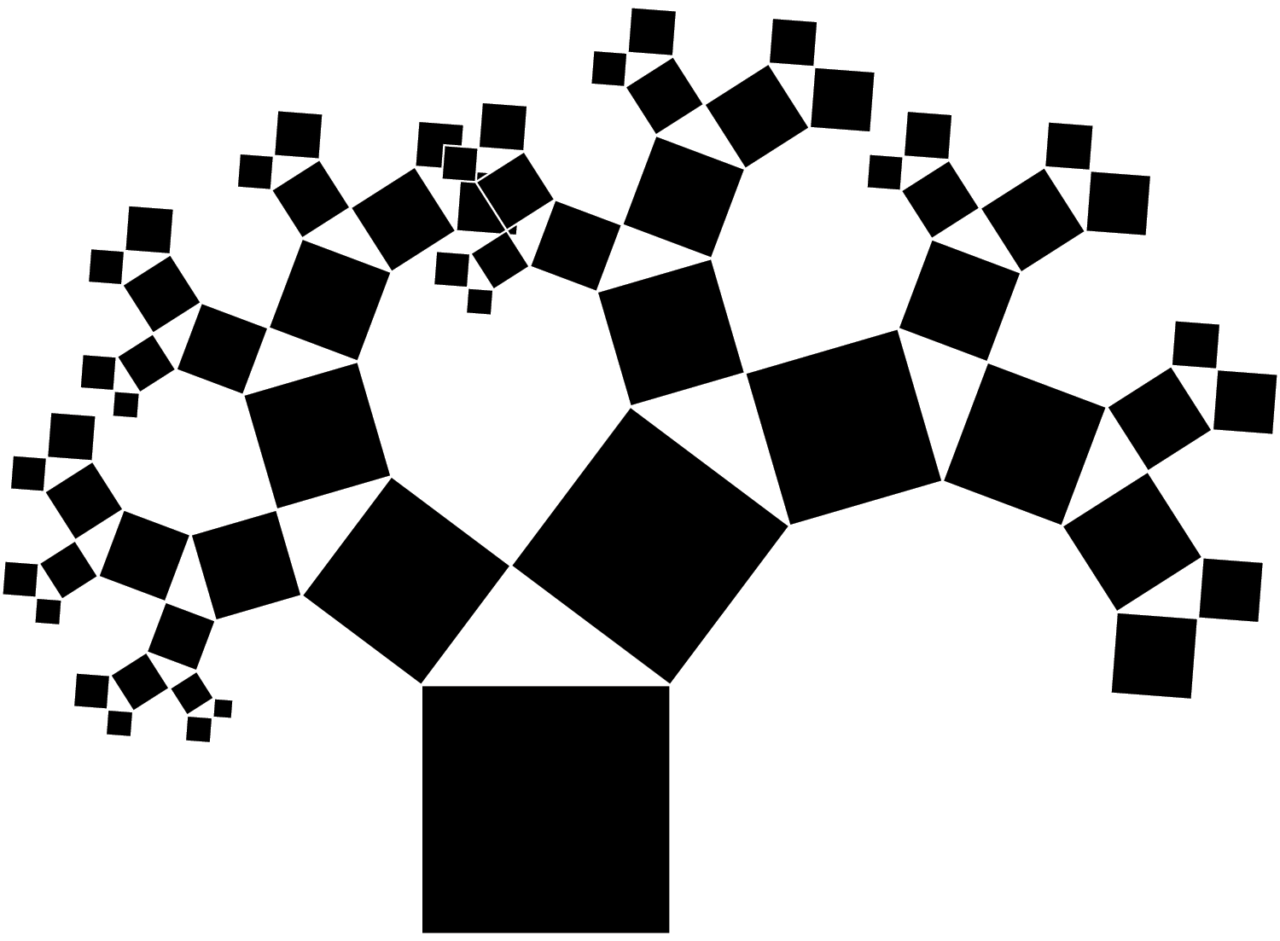

In our day, the departure from consensus reality began in innocent fashion, and with a different genre of entertainment: with wizards and dice rolls in 1970s basements. Board games, war games, and fantasy novels had all been around for a long time. What role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons pioneered was using the same gameplay mechanics not to fight tabletop wars but to tell stories, centered not on armies but on individual characters of a player’s own creation. The point of playing was not to beat your opponent but to share in the thrill of making up worlds and pretending to act in them. You might be an elven warlock rescuing a maiden, or a dwarven paladin breaking out of a city besieged by orcs. Or you might be the “dungeon master,” the chief storyteller who decides, say, whether the other players encounter a dragon or a manticore.

The role-playing game is to our century what the novel was to the eighteenth: the social art form epitomizing and evangelizing a new mode of self-creation. Role-playing games became especially popular in the 1980s, fostering a moral panic over the corruption of the youth, and their influence has continued to vastly exceed that of table-top games.

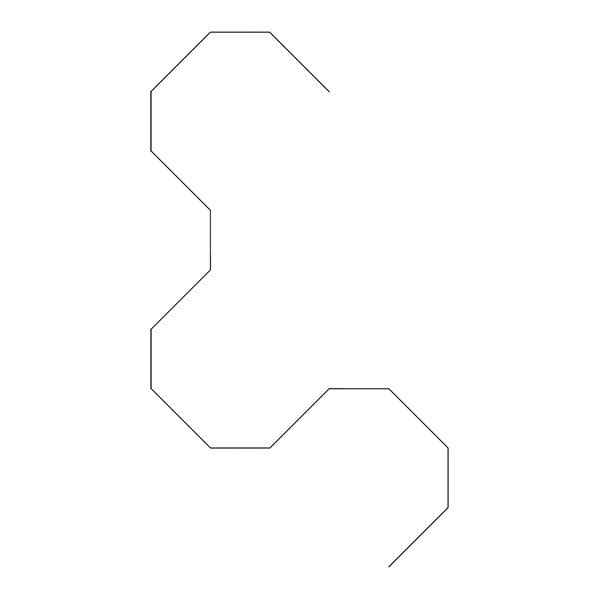

As soon as the scientists, students, and computer hobbyists who loved Dungeons & Dragons began connecting with each other through what would come to be called the Internet, they began to play games together. On top of the early text-based online world, they created chat protocols for role-playing games. It was an early form of what Sherry Turkle called “social virtual reality.”

Many of the systems we now use online have their structural origins in the world of role-playing games. Video games of all sorts borrow concepts from them. “Gamified” apps for fitness, language learning, finance, and much else award users with points, badges, and levels. Facebook feeds sort content based on “likes” awarded by users. We build online identities with the same diligence and style with which Dungeons & Dragons players build their characters, checking boxes and filling in attribute fields. A Tinder profile that reads “White nonbinary (they/her) polyamorous thirtysomething dog mom. Web-developer, cross-fit maniac, love Game of Thrones” sounds more like the description of a role-playing character than how anyone would actually describe herself in real life.

Role-playing games combined character-building, world-building, game masters telling stories, creating puzzles, and rules for scoring points and making decisions — all for having fun with friends in an imagined world for a little while. Could we have imported online all of these tools for building alternate realities without getting sucked into the game?

Several weeks have gone by since you picked your rabbit hole. You have done the research, found a newsletter dedicated to unraveling the story, subscribed to a terrific outlet or podcast, and have learned to recognize widespread falsehoods on the subject. If your uncle happens to mention the subject next Thanksgiving, there is so much you could tell him that he wasn’t aware of.

You check your feed and see that a prominent influencer has posted something that seems revealingly dishonest about your subject of choice. You have, at the tip of your fingers, the hottest and funniest take you have ever taken.

Digital discourse creates a game-like structure in our perception of reality. For everything that happens, every fact we gather, every interpretation of it we provide, we have an ongoing ledger of the “points” we could garner by posting about it online.

Sometimes, something will happen in real life that provides such an outstanding move in the game that it will instantly go viral. Conversely, we tend not to talk about things that are important but do not garner many “points.” So, for instance, there has been far less frothy discourse on Twitter and in the New York Times about the restoration of the multi-billion-dollar state and local tax deduction — conservatives give it only a few points for liberal hypocrisy, and for liberals it’s a dead-end — than about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s “Tax the Rich” dress — lots of points in many different worlds.

Alternate reality games dictate what is and is not important in the unending deluge of information — what gets points and what doesn’t. What falls outside of or challenges the story of a given game is not so much disputed as ignored, and whatever fits neatly within it is highlighted. Wanting to understand the facts in perspective cannot alone explain the level of attention paid to vaccine complications, maskless people on planes, drag queen story hours, or school book bans by neofascist state legislatures (have I made everyone mad?). ARGs are not about establishing the facts within consensus reality. They are about finding the most compelling model of reality for a given group. If your ads, social media feeds, Amazon search results, and Netflix recommendations are targeted to you, on the basis of how you fit within a social group exhibiting similar preferences, why not your model of reality?

Perhaps this helps to explain why fact-checking seems so pitiably unequal to our moment. Yes, unlike a genuine game, QAnon followers assert claims about the real world, and so they could, in theory, be verified and falsified. It isn’t all confirmation bias — surprise is still possible: The Pizzagate believer who in 2016 brought a rifle to a D.C. pizza place to rescue child sex slaves from a ring believed to involve Hillary Clinton was genuinely shocked that the building didn’t have a basement. But ARGs can keep going because there are a myriad of possible solutions to puzzles in the game world. Debunking only ever eliminates one small set of narratives, while keeping the master narrative, or the idea of it, intact. For QAnon, or contemporary witchcraft, or #TheResistance, or Infowars, or the idea that all elements of American life are structured by white supremacy, one deleted narrative barely puts a dent in what people are drawn to: the underlying world picture, the big story.

Months have gone by since you went down the rabbit hole.

You are now an expert. You have alienated a few old friends … but made some great new ones, who get you better anyway.

Now consider the following statement:

The more I learn, the more astonished I am that everybody else isn’t taking this story as seriously as I am. My eyes keep opening while other people are going blind.

To play an alternate reality game is to be drawn into a collaborative project of explaining the world. It is to lose, even fleetingly, one’s commitment to what is most true in the service of what is most compelling, what most advances a narrative one deeply believes. It allows players to neatly slot vast reams of information into intelligible characters and plots, like “Everything that has gone wrong is the product of evil actors or systems, but there are powerful heroes coming to the rescue, and they need your help.” Unlike a board game, this kind of world-building has no natural boundary. Players can become entranced and awe-struck at the sheer scale of information available to them, and seek to assimilate it into building the grandest narrative possible. They try to generate a story in which all of the facts they have piled up make sense.

So what if an alternate reality game really did keep on going, if it had no end point? It would amount to a simulation of the world. All aspects of “reality” that fit into the simulation, including some produced artificially by players for fun and profit, would be incorporated. If the game had no boundary, at some point you could think that the world it is building simply is the world. In one early ARG, after the final puzzle had been solved, some participants winkingly suggested they next “solve” 9/11.

ARG game masters have described one of the pathologies of players as apophenia, or seeing connections that aren’t “really there” — that the designers didn’t intend — and therefore pursuing red herrings. In one game, in which players had to look for clues in a basement, some scraps of wood accidentally formed the shape of an arrow pointing to a wall. Players believed it was a clue and decided they needed to tear down the wall to find the next clue. (The game master intervened just in time.) But the difference between true and false interpretations exists only if the puzzle has one right answer, or one central authority — like J. K. Rowling intervening in fan debates about which Harry Potter characters are gay. The puzzle that today’s media consumers are trying to solve is the world, and interpretations are more or less up for grabs as long as they fit the story.

In a world in which we all play alternate reality games, we each pile up superabundant facts, theories, and interpretations that support the main narratives, and our allegiances gradually solidify as we consume and produce the game material. It’s not just interpretations of data that wildly diverge between different games, but also players’ sense of what is realistic or plausible — for example, their perceptions of the rates of homicides committed by police, or by illegal immigrants. This means that, in any crisis situation, the most narrative-enhancing reports will spread widest and fastest, regardless of whether they are overturned by later reporting. As L. M. Sacasas noted about the media experience of January 6, “a consensus narrative will almost certainly not emerge.”

The cynical reader might interject that the bygone era of mass media was not a golden age of truth, but was subject to its own overarching narratives and its own biased reporting. But what matters here is that mass media, rooted in an advertising business model and in broadcast technologies, created the incentives and capability for only a small number, perhaps even just one, of these narratives to emerge at one time. Both journalists and spin doctors attempted to massage or manipulate the narrative here or there, but eventually mass media converged on whatever the narrative was. In an age of alternate realities, narratives do not converge.

As the media ecosystem produces alternate realities, it also undermines what remains of consensus reality by portraying it as just one problematic but boring option among many. The process of arriving at this contrary view of the consensus — a process sometimes called “redpilling,” after The Matrix — goes something like this: A real-world event occurs that seems important to you, so you pay attention. With primary sources at your fingertips, or reported by those you trust online, you develop a narrative about the facts and meaning of the event. But the consensus media narrative is directly opposed to the one you’ve developed. The more you investigate, the more cynical you become about the consensus narrative. Suddenly, the mendacity of the whole “mainstream” media enterprise is laid bare before your anger. You will never really trust consensus reality again.

Opportunities for such redpill moments are growing in frequency: the 2016 presidential election, the George Floyd protests, masking and lockdowns, the crime wave in American cities. There were always chinks in consensus reality — think of the newsletters of the radical right or the zines of the leftist counterculture — but finding consensus-destroying information was costly. The process was unable to produce the real-time whiplash of today’s redpill moments. The speed at which events like these are piling up suggests that the change is structural, that it is the media ecosystem itself that is fundamentally transforming.

For our final game, please consider a troubling episode of dreampolitik from very recent American history.

Driven by devastation over the outcome of the presidential election, brought together by algorithmic recommendations on social media feeds, fueled by information overload, loosely organized by networks of influencers, egged on by massive ratings and follower counts, and strengthened in the loyalty that comes with telling an audience what it wants to hear, committed media game players created an alternate reality in which the good guys were working behind the scenes to bring down the bad guys. The story of secret activity that would end the hated presidency at any moment became detached from the actual government investigations underway, from verifiable facts, from discernible reality.

Is the paragraph above a description of …

Pick one.

My argument here is not that we are all the way into Wonderland, or even close to it yet. But that qualification should be as worrying as it is reassuring.

The change I am outlining is in most parts of the media world still fairly subtle — the addition of a new valence in how we see actors interpreting information, sharing content, and choosing what to emphasize. The real world still exerts hard pressure on the narratives people are willing to accept, and the realm of pure fantasy remains that of a small fringe. Yet while game-like media habits are easiest to see and most pronounced in Q-world, we can already see some of the same activities, engrossments, and intuitions that are involved in playing an alternate reality game creeping into the broader media ecosystem too — even in sectors that pride themselves on providing the sane alternative, the lone voice of reality. The point here is not to draw a moral equivalence, or to say that all these actors have lost their grip to the same degree, but rather to suggest a troubling family resemblance. The underlying structure of the reality-gamesmanship we find in, say, Infowars has its counterpart in, say, Trump-era CNN: incentives and rewards, heroes and villains, plotlines, reveals, satisfying narrative arcs.

To be a consumer of digital media is to find yourself increasingly “trapped in an audience,” as Charlie Warzel puts it, playing one alternate reality game or another. Alternate reality games take advantage of ordinary human sociality and our inherent need to make sense of the world. All it takes for the media environment to begin functioning like everyone is playing alternate reality games is:

Internet brain worms thrive on these ingredients. As long as spending more time consuming media — whether Facebook, MSNBC, talk radio, or whatever — increases the strength of one’s exposure, the worms will find their way. Reality as we understand it is a phenomenon of social structures, language, and shared processes for engaging with the world. Digital media is remaking all of these in such a way that media consumption more and more resembles the act of playing an alternate reality game.

The recent rise of subscription newsletters on the platform Substack has provided a powerful if depressing natural experiment of this phenomenon. Freddie de Boer and Charlie Warzel, both widely read commentators, have written about tinkering with their own Substack content, finding that calibrating posts to engage with Twitter controversies of the day led to exploding levels of clicks and new subscriptions, while sober, calm content was relatively ignored. Writers who get their income directly from subscriptions have every incentive to provide red meat day after day for some particular viewpoint. Sensationalism is of course as old as the news itself, but what targeted media like newsletters provide is the incentive to be sensationalistic for niche audiences. There is a reward for spinning alternate realities.

When writing for niche audiences, more status accrues to sharing narrative-enhancing facts and interpretations than to sharing what most of us can agree is reality. Those who quixotically hold on to the TV-era norms of balance and fact-checking won’t find themselves attacked so much as bypassed. By a process of natural selection, attention and influence increasingly go to those who learn to “speed-run through the language game,” to borrow from Adam Elkus, laying out juicy narratives according to the incentives of the media ecosystem without consideration of real-world veracity.

Business analytics will continue to drive this divergence. To illustrate the pervasiveness of this process, consider the logic by which The Learning Channel shifted from boat safety shows to Toddlers & Tiaras, and the History Channel from fusty documentaries to wall-to-wall coverage of charismatic Las Vegas pawn shop owners and ancient aliens theories. Content producers have an acute sense of which material gets the most views, the longest engagement, and the highest likelihood of conversion into subscriptions. At every step, every actor has the incentive to make the media franchise more of what it is becoming.

It’s an alien life form.

- David Bowie about the Internet, 1999

It is tempting to believe that, sure, other people are headed into Wonderland, but not me. I can see what’s happening. What if, say, you are not online, or don’t even pay much attention to the news? Even if your picture of the world is determined mainly by conversations with friends and family, you will find yourself being drawn into an alternate reality game, based on the ARGs they are playing. These games have “network scale” — they are more fun and powerful the more people you know are involved. This is also why it is becoming more and more difficult, and unlikely, for people playing different games to even talk to each other. Indeed, a common conceit of some media games is that “nobody is talking about this.” We are losing a shared language. It is not that we arrive at different answers about the same questions, but that our stories about the world have different characters and plots.

It is increasingly undeniable, looking at revealed preferences, that people can come to value their digital communities, relationships, and realities more than those of “meatspace,” as the extremely online call our enfleshed world. “For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” Every year, consumers spend billions of dollars on skins, costumes, and other “materials” in video games. Digital “property” like cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens have exploded. People attend events, show up at rallies, and even take vacations in order to post about them online. Many users on Reddit last year spent thousands of dollars on shares in the seemingly failing video game retailer GameStop, some declaring that they were prepared to lose the money, to send a message and garner status and make great “loss porn.” Recently, a player annoyed at the way the U.K.’s Challenger 2 tank was modeled in a video game posted classified documents to a game forum to make his point.

More than money, some participants in alternate reality games are willing to risk their lives and freedom. Over the past few years, Americans deeply immersed in their online versions of reality, driven by the desire to either influence them or create content, have: broken into a military facility, murdered a mob boss, burned down businesses, exploded a suicide car bomb, and stormed the Capitol.

Those who have studied the past should not be surprised. The most contested subjects in human history have arguably not been land or fortunes, but symbols, ideas, beliefs, and possibilities. As much blood has been spilled over products of the mind as of the body. The growing dominance of the Internet metaverse over “the real world” is just the next step in the story of man the myth-making animal.

You do not have to surrender your commitment to facts to participate in an alternate reality. You just have to engage with one, in any way. If you are a user of digital systems, if you allow them to provide you recommendations, if you train them on your preferences, if you respond in any way to the likes, downvotes, re-shares, and comment features they provide, or even if you are only a casual user of these systems but have friends and family and people you follow who are more deeply immersed in them, you are being formatted by them.

You will be assimilated. ♠

Jon Stewart has a dream where he walks out onto the brightly lit set of a new TV show. He has worked for years to build this show. It’s the answer to everything wrong with the news media.

For decades, Americans were fed a news diet of mass-produced garbage. O. J. Simpson, Monica Lewinsky, endless coverage of the Laci Peterson disappearance … hour after hour of filler. Talking points and “spin rooms” and canned zingers. Presidential aspirants doing eighth-grade debate theater. It was empty both-sides centrism. It didn’t speak to what mattered. It staged fake confrontations with powerful people to protect them from real accountability.

On this new show, yes, figures from across the political spectrum come to argue. But now it’s only real disagreement about the issues that matter to real Americans. No more treating politics like a staged wrestling match, only authentic single-warrior combat.

And the show does real reporting too, hard-hitting exposés on the issues other shows ignore. Reports about the billionaires who lined their pockets on the opioid crisis. Reports about warmongering elites lying so they can send working-class kids to die across the world. Reports about ideological indoctrination in public schools.

Gone are the manufactured news cycles on gaffes and the horse race. This show doesn’t let politicians duck behind talking points, but makes them say where they really stand on the issues. Gone is the view from nowhere, which was just a cover for manipulative slant. The host tells you straight what he really thinks and why it matters.

The old world of journalism is finally dying and this is the new one. Corporate shills didn’t think it could make money — and they didn’t want it to. They didn’t believe Americans would watch this. They didn’t believe in Americans at all.

But people are watching, by the millions. It’s raking in money hand over fist. Jon Stewart was right and the suits were wrong.

He saunters onto the set. He is ready to take his seat.

Only then, like Scrooge in the graveyard, does he see the name on the host’s chair. It isn’t him. It isn’t Stephen Colbert. It isn’t even Brian Williams. It’s a name from his past, a name that sends a chill down his spine and turns him pale. In his mind he hears a high-pitched whine and smells the sickly whiff of fresh bowtie.

How did Jon Stewart’s dream become his nightmare?

The problem was that he misunderstood what made the monolithic mass media world a financial success. He was convinced that you could keep all the business structures basically the same, and just replace the media’s phony reality with an authentic one. There would still be one huge audience, but now instead of being forced to crowd around a trough to guzzle slop, they would join together as one to break bread.

And nobody would have to worry about the money. The meal would be so nourishing, the conversation so lively, the feast so grand, that that part would just work itself out.

Stewart in his heyday was a man before his time. He wasn’t just a prophet of the new world to come; he was its chief architect. He would pioneer everything that made it work.

And he was dead wrong, too. In the world he was building, there would be no grand feast. As he tore down the pillars of the phony old consensus reality, he was laying the foundation for authentically fanatic alternate realities.

In our bizarro world, Jon Stewart’s fantasyland is real, and its king is none other than Tucker Carlson.

Even for those of us who lived through it, it is difficult to remember or explain what postwar America’s mega-saturated media monoculture was like, and how dramatic the shift away from it has been.

In the Nineties, the American mind was drenched in carefully constructed corporate messaging conveyed by a never-ending torrent of ephemeral media — countless TV channels, newspapers, magazines, and radio shows. Catchphrases, brand logos, product placement, and celebrity gossip were the psychic detritus. We were all swimming in it, and it was about nothing, nothing except itself.

Jon Stewart was not an activist when he took over The Daily Show on Comedy Central, a trifling basic cable channel, in 1999. But as a comedian he had a feel for the absurd, and nothing had grown more absurd in his mind than TV journalism, suffused with spin, fake debates, soft interviews, and celebrity politicians.

If you weren’t tuned in to the zeitgeist when the show mattered — roughly spanning the 2000 election to the Global Financial Crisis — here’s a refresher.

Stewart’s Daily Show was structured like a standard half-hour news show mixed with a talk show. It opened with an anchor at a news desk offering a quick rundown of the day’s top headlines. He then handed the show off to correspondents, who offered analysis from the studio, or produced on-location reported story segments in the style of weekly newsmagazine shows like 60 Minutes. Finally, the anchor interviewed a single subject at the anchor’s desk, in the style of Johnny Carson or Jimmy Kimmel.

The twist: It was fake. The rundown was actually a series of jokes about the headlines. The correspondents interviewed real people about real stories, but the setup was a gag, the correspondents acting in character to see what reactions they could get. And the whole thing was broadcast before a studio audience, who giggled and hooted and hollered like they were on Springer.

If you watched a field segment in the Stewart era and thought the correspondents were mocking real people, you were missing the point. They were making fun of themselves, their own characters. Each one was a send-up of a particular TV-journo type.

Rob Corddry, feigning ludicrous outrage at minor annoyances, was spoofing John Stossel’s blowhard “Give Me a Break” segment from 20/20. Stephen Colbert, the ultimate self-serious straight man, was aping Stone Phillips and Geraldo Rivera. “He’s got this great sense of mission,” an out-of-character Colbert said of Geraldo. “He just thinks he’s gonna change the world with this report.”

The brand Stewart had inherited was dedicated to little more than wacky jokes and pop-culture infotainment. Stewart would turn it into a tightly written, ironic ongoing commentary on politics and journalism. It became less about the news and more about news itself. It was about the pretensions and foolishness of the doofuses who said they were doing the real thing.

And the clips. The clips!

The feature that really made The Daily Show famous was its masterful use of archival video clips to reveal the hypocrisy of the chattering classes. Stewart would set his target on some party shill or professional talking head being condescending, self-important, dishing out blame, kissing whatever ring he’d been paid to kiss. And then the show would play a clip of the same talking head’s appearance on a C-SPAN 3 four-in-the-morning call-in show from ten years ago, back when he’d been paid to kiss another ring, saying the exact opposite thing.

There was a clip, there was always a clip. And our righteous host would send these hacks packing.

Through all this, certain public figures would be transformed into storylines with narratives and characters, with inside jokes and recurring bits. The media’s storytellers became the subjects of a theater of the absurd. It got so that when certain figures would show up in a segment, you knew you were about to witness them receive their just comeuppance, a great spectacle of spilled archival blood. The audience would titter in excited anticipation.

It was a delight to watch.

And it was a hit. In a glowing 2003 interview, Bill Moyers called Stewart “a man many consider to be the pre-eminent political analyst of our time,” a status he would enjoy for a decade.

But there was always a tension in the enterprise, a risk that in taking down these bloviating figures, his own head would grow too big. And the risk was made worse because, strangely, Stewart never understood the source of his success. At least, he acted like he didn’t.

At the heart of his crusade, as he saw it, was a fight with media’s corporate overlords over whether news had to be dumb to make a buck. Stewart had no desire to just make another TV show. At a time when most political comedy was aimed at personal quirks, gaffes, and scandals, he maintained, like his hero George Carlin, a high view of comedy as an art form for social commentary.

But, as he retells it, the suits believed that to be profitable, a late-night show had to focus on pop culture. Earlier this year, talking about how he came to The Daily Show’s helm, Stewart recounted what he said to them: “Let’s make a deal. Let me do the thing that I believe in. And if it sucks and it doesn’t sell you enough beer, you can fire me.”

With a crack writing team, a distinctive vision, and a stable of generational comic talent, The Daily Show sold beer and then some. By the end of his run he was personally earning $25 million a year, making him not just the highest-paid host on late-night television but possibly in the entire news business — higher than Letterman, than Matt Lauer, than Brian Williams. “We developed the thing that we believed in and the audience showed up.”

If you build it, they will come. The corporate idea that Americans wanted canned news instead of viewpoint journalism and hard-hitting interviews of politicians was a lazy excuse masquerading as a market analysis.

Call it Stewart’s Content Theory: The real reason conventional news sucked was, well, because it sucked. It was bad because nobody had tried to make it not bad. Maybe producers didn’t have the guts, maybe journalists were addicted to access, maybe it was just the inertia of the whole system. Maybe they needed a prophet to help them see the light. Whatever the case, the answer was simple: Instead of choosing to be phony and bad, they should choose to be real and good.

Nothing was stopping reporters from flipping this switch. If you had an authentic viewpoint that took the audience seriously, presented with boldness and creativity, you could both entertain and inform, and find enough advertisers to pay for it all. After all, The Daily Show did.

So if it was that easy, why wasn’t everyone else doing it too?

There was an alternative theory for why news was so terrible: The structure of the news business itself dictated what journalism could be.

The growing shallowness of American journalism had a surprising source: the fairness doctrine. The 1949 regulation is remembered today as a “both-sides” mandate, requiring that TV and radio broadcasters who gave air time to one side of a public controversy had to give equal air time to the other. But it had another, largely forgotten component: As a condition of their license, it required that broadcasters air news coverage in the first place. For the first several decades of television, corporations thus viewed their news divisions as a public service, a necessary cost of maintaining their overall brand, and a checkbox to ensure their legal right to operate.

As early as 1961, American historian Daniel Boorstin had raised the alarm about how the mandate to churn out news was warping our media diet. He coined the term “pseudo-event” to describe things that happen simply in order to be reported on. For Boorstin, the driver of pseudo-events was a reversal from gathering the news, as events dictated, to making the news, as a standardized product on a schedule.

The larger your news-making enterprise, the more events you needed to have to fill airtime. When you ran out of events of true public note, you turned to pseudo-events: interviews, press conferences, and other PR exercises, plus interpretations, analysis, and opinion about the same. Thus the mass-produced phoniness Stewart would lampoon.

Paradoxically, after the end of the mandate to make news there was actually an increase in coverage.

In 1987, the Federal Communications Commission abolished the fairness doctrine. But at the same time, cable was rising and content needed to be produced on an even greater scale. With greater competition among channels, and no more law that rationalized tolerating losses on news, the industry insisted that news divisions turn a profit like any other.

But producing the news had huge fixed costs. You needed studios, journalists, and correspondents around the globe, regardless of how many hours of coverage you aired. And so the simple solution to generating profits was to spread those costs out, producing more news across more channels within the same corporations.

The strategy worked. After the repeal of the fairness doctrine, the production of TV news exploded, from an hour or so a day on each of the big three networks to continuous, 24/7 coverage across multiple networks. NBC News had been losing $100 million a year when GE bought the network in 1986. By 1998, the division earned $200 million in profit, drawing revenue from its ratings-dominating broadcast programs Today, Dateline, and NBC Nightly News, its cable channels MSNBC and CNBC, and an online news venture with Microsoft.

Nineteen ninety-nine was what we might call the Year of Peak News, the year this media culture and the industry driving it were at their zenith. It was the peak of the Lewinsky plotline in the form of the Clinton impeachment trial, and the peak of the self-fueling pyre of journalistic importance surrounding it — the more that TV covered it, the more important it became. It was the year that the respected journalists Tom Rosenstiel and Bill Kovach, in their book Warp Speed, warned that competition for attention and ad revenue had created an alternative media reality entirely separate from what really mattered for the country. It was near the point that more Americans were working in media than ever had before or ever would again — industry employment peaked at 1.6 million in July 2000 and never returned.

Nineteen ninety-nine was also the zenith of a powerful counter-cultural backlash. The problem wasn’t just the news. It was how the entire consumer culture powered by mass advertising was rotting our souls and immersing us in unreality. Nineteen ninety-nine was the year American Beauty won Best Picture and The Matrix invited us to take the red pill. It was the year that Fight Club warned, “Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don’t need…. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our great war is a spiritual war.” Call it the Year of Peak Fight-the-System.

Would reform be enough, or did there need to be revolution? In 1999, an influential group of activists argued that nothing could change until mass advertising’s grip on the news industry was broken.

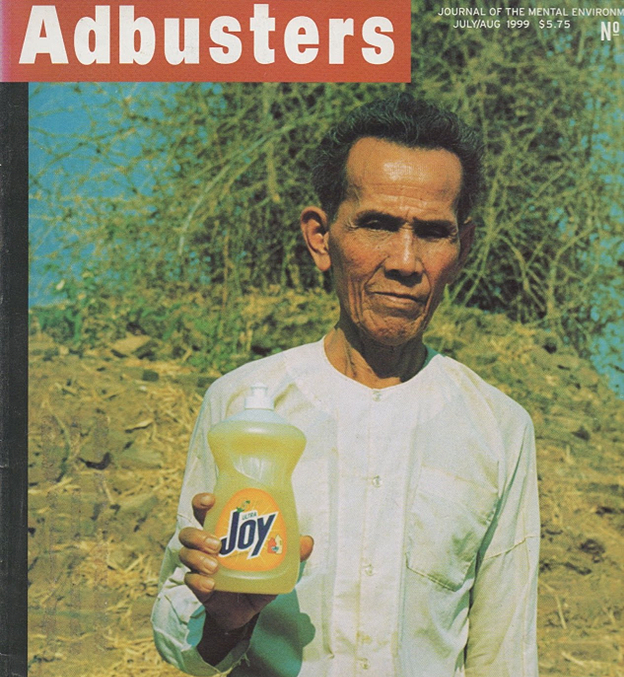

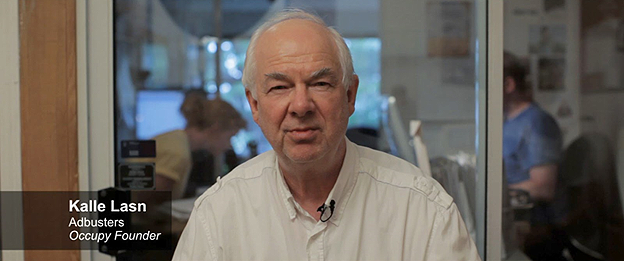

That year, Kalle Lasn published his landmark book Culture Jam. Lasn, a founder of Adbusters magazine and a former market researcher, had come to see the stranglehold of corporate media as the meta-problem making progress impossible for left-wing movements. In the 1980s, he had begun trying to work within the system, buying short environmentalist and anti-consumerist commercials, only to be almost universally turned down by the networks.

Station owners’ reticence made sense. Newspapers, television, and radio all ran on advertising. Advertising existed to spread corporate brand messages, and its value was based on how much consumption it drove. As Lasn had shown, you couldn’t even buy airtime for a fair hearing of ideas that ran counter to the interests of advertising. Authenticity was impossible within the system. American culture had become a corporate product, sponsored by advertising-based mass media.

Lasn was joined by Naomi Klein, whose book No Logo was also published in 1999 — days after the “Battle in Seattle,” a protest against the World Trade Organization, began in earnest. All blamed the ravages of free trade and global finance on the corporate takeover of the public square. They proposed a set of “culture jamming” tactics to push back — protests and petitions, counter-marketing, brand hijacking, “subvertisements.”

Call this Lasn’s Structure Theory: The reason news sucked was that the economics of the news business required it to suck. The suits were right after all.

It’s hard to remember how pervasive the structural critique was in the Nineties, and to appreciate how thoroughly it has vanished from public life. Pretty soon you stopped hearing about how advertising and brands and consumerism were eroding civic life. Lasn’s Structure Theory faded away.

Perhaps that had something to do with that other notable event from The Year of Peak News: Jon Stewart’s ascension to the Daily Show throne.

On the surface, Stewart, with his counter-establishment, anti-corporate message, sounded a lot like these activists. But Stewart’s Content Theory was that you could stage a revolution against the system from within.

The showdown between legacy media and Jon Stewart’s real fake news insurgency reached a head in October 2004, when he sought out a duel with a show that stood for everything he reviled about political journalism.

The show was CNN’s Crossfire. It featured one liberal host and one conservative host who would debate the issues of the day. Usually they were joined by one liberal guest and one conservative guest who did more of the same. These talking heads recited their talking points, all nice and neat. Afterward they probably all headed out to the same cocktail party.

From the start of the segment, you could tell that the hosts didn’t stand a chance. They were dutifully antagonistic with Stewart, but they were tired old welterweight champs who didn’t see the new generation of fighter standing before them in the ring.

Stewart was as funny as ever, but this time without the ironic grin. His face was stony. He was mad.

“We need help from the media, and they’re hurting us,” Stewart implored the hosts. “It’s not so much that [this show] is bad, as it’s hurting America.”

“Let me get this straight,” the liberal host replied. “If the indictment is … that Crossfire reduces everything … to left, right, black, white. Well, it’s because, see, we’re a debate show.” “We have each side on, as best we can get them, and have them fight it out.”

Stewart would have none of it. “After the debates, where do you guys head to right afterwards?…. Spin alley.” He was talking about how, after formal debates, reporters would interview campaign flaks whose job was to argue why their guy had won, regardless of what had actually happened. “Now, don’t you think that, for people watching at home, that’s kind of a drag, that you’re literally walking to a place called ‘deception lane’?”

It wasn’t real debate — it was fake. “What you do is not honest, what you do is partisan hackery.” Instead of helping the people, “you’re helping the politicians and the corporations…. you are part of their strategies.”

In the countless retrospectives that have been written on the Crossfire showdown, which became one of the defining media moments of the 2000s, much has been said about Stewart’s hypocrisy. One of the hosts pointed it out: “You had John Kerry on your show and you sniff his throne and you’re accusing us of partisan hackery?” Stewart ducked this lamely: “You’re on CNN. The show that leads into me is puppets making crank phone calls. What is wrong with you?”

But what matters isn’t that Stewart was a hypocrite. It was how masterfulThe Daily Show was at leveraging this double standard.

In a monologue during the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Stewart joked that “our show obviously is at a disadvantage compared to the many other news sources that we are competing with…. For one thing, we are fake.” But of course the subtext ofThe Daily Show was that all TV news was fake news, and everyone else was just lying about it. Being honestly fake wasn’t a liability. It was a huge asset.

The Daily Show really was news. It covered the basic facts of the stories of the day. Its viewers were about as well-informed as those of broadcast or cable TV news. And surveys showed its newscasts were as trusted as many mainstream media sources.

And because it made no pretense of “fairness” or “objectivity,” it had an enormous advantage in competing for the eyeballs and allegiances of its young audience. Because its only explicit loyalty was to the laughs, the show could ignore “the news cycle” and focus on the stories that hit the right notes for its audience. Even as Jon Stewart fought a world of empty spin, he pioneered a model of television news where you didn’t need to manage the reporting, the sources, or the production of compelling televisual imagery. By wresting control of the context, you could bend it to your will and tell the story you wanted to tell.

The genius of The Daily Show wasn’t that it was great in spite of everyone else sucking; it was great because everyone else sucked. As long as there was an endless supply of garbage on hand — and boy, was there — you could do a show that was just about the garbage. And, perversely, you could be more successful talking about the garbage than making it.

Stewart was a critic of the system, and also its greatest dependent. Did he really not get this? For a moment in the Crossfire showdown, it seemed like he did: “The absurdity of the system provides us the most material…. the theater of it all.”

Three months after the matchup, Crossfire was canned. CNN’s new president, Jonathan Klein, said that he wanted to move the network away from “head-butting debate shows” and toward “roll-up-your-sleeves storytelling,” adding, “I agree wholeheartedly with Jon Stewart’s overall premise.”

But was the new model for news really just going to be a more earnest, informative version of the old?

You didn’t even have to listen to the Crossfire segment to know that it wasn’t just a drubbing but the birth of a new world. You could see it on the hosts’ faces. The establishment had lost the plot.

The liberal host, Paul Begala, kept trying to change the subject. On his face you could see the dumbstruck look of the compliant citizen murdered on the roadside by Anton Chigurh in No Country for Old Men. After Crossfire was canceled he never hosted his own television show again.

The old world was dying. You could ignore this and double down, or you could learn how to stand outside legacy media — and wield this to your advantage.

The conservative host tried valiantly, jousting like he was untouched. But as the segment wore on, his voice kept going higher, he sounded desperate. “I think you’re a good comedian,” he told Stewart. “I think your lectures are boring.” But by the end of the segment, you could see the wheels turning in his head.

His name was Tucker Carlson.

The Daily Show was a pioneer of the above-it-all style. But its weapon was not pointed parody alone.

When the Global Financial Crisis struck, Stewart was still at the height of his influence. Once again he saw a case of the media’s interests running opposite to the people’s. He was ready for another showdown.

In February 2009, CNBC pundit Rick Santelli had delivered an angry rant against a government bailout for “losers’ mortgages.” He floated the idea of holding a “Chicago Tea Party,” where “derivative securities” would be dumped into Lake Michigan. The diatribe would soon ignite the populist, right-wing Tea Party movement.

Stewart was righteous with indignation. Two weeks later, he aired clip after damning clip of CNBC pundits offering horribly wrong investment advice leading up to the financial crisis. He topped it off with a monologue indicting the chumminess, corruption, and self-dealing of finance and financial journalism.

One of those pundits, Jim Cramer, the host of CNBC’s Mad Moneyand the most famous financial pundit on TV, would defend his record on his show and write an op-ed calling for “a real debate.” Stewart then broadcast a patient and lethal blow-by-blow of Cramer’s advice to buy what would turn out to be rotten stock in Bear Stearns.

In March, within days of the stock market bottoming out, Cramer showed up for an interview on The Daily Show. In the segment — billed in news outlets as “Stewart vs. Cramer,” like a boxing match — Cramer got the treatment the audience knew was coming.

But there was a new twist. Usually, The Daily Show would air archival clips framed by Stewart’s solo narration. This time they were being deployed in real time against a subject who was sitting right there in the guest chair. Stewart would say something about Cramer’s chummy relationship to the financial system. Cramer would dodge and weave and try to recontextualize. And then Stewart would call out, “Roll 210,” and out would come some obscure footage of Cramer himself from his hedge fund days, peddling the very kinds of shenanigans that had led to the crisis. Over and over. It was devastating.

For the first time, facts had caught up to spin. Rather than leaving it at great gotcha TV, Stewart used the clips and his back-and-forth with Cramer to fuel a compelling cri de coeur about corruption on Wall Street.

Just like the Crossfire appearance, it was a beautiful thing to behold. How were the Daily Show staff so damned good at this? The question bedeviled Stewart’s competitors — one profile noted that “how the show’s producers find the source video for these elaborate montages has been a bit of a trade secret.”

What had created a culture of “just talking on TV without any accountability,” as one Daily Show writer put it, was not only the sheer volume and speed of the news. It was this true fact that will sound insane to anyone under the age of thirty: People on television reasonably assumed that no one would hear what they had said ever again.

As essayist Chuck Klosterman records in The Nineties: A Book, the key characteristic of twentieth-century media was its ephemerality. You experienced it in real time and internalized what was important and what it felt like. Then you moved on. “It was a decade of seeing absolutely everything before never seeing it again.”

People used to argue with their friends about the plot of a show or what the score had been in the ball game because, well, how were you going to check? Unless you had personally saved the newspaper or recorded it on your VCR, you would need to go to a literal archive and pull it up on microfilm.

TV news was even shakier, as networks often recorded over old tapes. Some of this footage only exists today because of the obsessive efforts of one Philadelphia woman who recorded news broadcasts on 140,000 VHS tapes over forty years.

And so, if you were a pundit or a commentator or a “spin doctor” PR flak, you could say whatever suited your needs at the moment, or even lie with impunity — as long as your lie did not become its own pseudo-event. Your lasting impact was whatever stuck in viewers’ heads and hearts. And if you changed your tune in the months or years afterwards, who would remember?

The Daily Show would remember.

The explosion of live broadcast and cable news had created a new, completely under-valued resource for whoever thought to harness it: catalog clips. Soon, new digital technology could preserve content in amber, allowing for its retrieval, repurposing, or referencing at any time.

Another signal event from 1999, the Year of Peak News: The first digital television recorder, TiVo, came onto the market. At a time when news networks sent out old footage by postal mail, the TiVo made it possible for Daily Show producers to record, catalog, and comb through hundreds of hours of footage a week. Their process became substantially more powerful in 2010 with the deployment of a custom, state-of-the-art system that both captured footage and converted its audio to text, allowing producers to search for just the right clips across the entire accumulated archive.

The Daily Show always portrayed itself as the David to the news establishment’s Goliath. But in the showdown, Cramer pointed out the advantages the show had when it came to the production mechanics of filling air time. “We’ve got seventeen hours of live TV a day to do…. I’ve got an hour, I’ve got one writer, he’s my nephew…. You have eighteen guys.”

Stewart liked to claim that they were just jokers, but really the joke was on everyone else. The Daily Show had figured out how to produce a real, high-quality newscast after all — without having to do any of its own reporting. Under the “fair use” copyright exception for parody, the show could simply steal whatever content it needed from its competitors.

The evening news had to send its correspondents to exotic locales. Sure, The Daily Show would sometimes do the same. But it also had a recurring joke about using the studio green screen to do its “field” interviews.

For legacy media, you needed to always be producing the news. The Daily Show’s incentives were reversed: It could dine out on a viral clip for weeks, and there was an ever-expanding universe of recycled material to work with and a bevy of writers to use them.

It wasn’t just the ironic style of the show, then, that allowed it to turn real people into characters in ongoing narrative arcs. It was their remarkable use of technology to build an ever-growing database of content. When Stewart later said, “We were parasitic on the political-media economy, but we were not a part of it,” he was only right about the first part.

Against spin and vacuity in political journalism, Jon Stewart harnessed the past as a weapon. It was The Daily Show, more than any other factor, that began the disciplining of American political culture with perfect digital memory.

Even as Stewart was turning the content and production models of legacy news into a joke, its revenue model was about to be destroyed too. In the 2000s, two major innovations on the Internet tanked the economic value of offering homogenized content to a mass audience.

In the Year of Peak News, there was only one game in town when it came to advertising. Producers of content, and advertisers along with them, were competing for as many eyeballs as possible. They were effectively trying to reach everyone. A publication made money based on how large a piece it cut out of this single massive pie.

It is often said that what destroyed the legacy advertising model was the Internet, but that isn’t quite true. The Internet operated for many years without touching the mass advertising business. That giant would eventually be felled by Google, but initially the company refused on moral principle to make money from advertising. In a 1998 paper, the company’s founders wrote that search engines funded by ads “will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers.” Instead, Google sold licenses to other companies to use its search technology. But amid the pressures of the dot-com bust, the company would backtrack and pursue a new revenue stream based on targeted search ads, launching Adwords in October 2000.

During the aughts, the new personalized digital advertising business made mass advertising ever less valuable. For businesses, targeted ads were much more effective than ads aimed more or less at everyone, even with the existence of niche publications and demographic segmentation. If you were a sports memorabilia company, why target everyone who read Sports Illustrated when you could directly target people who searched online for old MLB tickets?

In the Year of Peak News, there was also only one game in town when it came to how consumers got their information. For half a century, if you wanted to know what was happening, you had to buy the paper or sit through eight minutes of ads during the nightly news. There was a seller’s market for information, and so producers could make money just by providing access. Even local newspapers thrived on this scarcity — decades of vital local journalism was funded in large part by readers who just wanted to know whether the Packers won last night.

Even in the early 2000s, the legacy media business model was still protected by this moat. Yes, the Internet existed, but the world’s information was mostly not online, and it was not well organized. Most of the content you saw on the early Web was not yet compiled automatically. In many cases, curation — adding and organizing content — was still done, quite literally, by hand. Even “cutting-edge” search services like Ask Jeeves, which advertised its amazing question-and-answer technology, had to employ legions of writers to help produce answers to queries. Because Web 1.0 offered roughly the same information abundance as before, legacy media maintained its monopoly on attention, and subscription and classified and advertising dollars kept flowing.

All this too would change as Google and others pioneered the technologies for automatically collecting, aggregating, and curating information online. A decade later, nobody was buying the daily paper to find out the Packers score. Now all you had to do to find out what was happening was open Google News, and you had your pick of headlines from a thousand different sources. Why would you pay for any of them now?

These were the two pillars of the new media world: Personalized digital ad tech was destroying the value of the mass audience. And automatic aggregation was making information superabundant, and so far less valuable.

Mass advertising soon declined while online advertising boomed. Newspaper ad revenue reached a historic peak of $49 billion in 2005 before plummeting to just $20 billion in the following decade. In 2010, online ad sales surpassed newspaper ad sales for the first time.

If the media world wanted to survive, it would have to figure out how to turn lemons into lemonade — how to make money from a narrow rather than a mass audience, and how to harness massive amounts of cheap information and create something valuable on top of it.

Our fearless hero was set to lead the way.

Would you be surprised to learn that Jon Stewart was a fan of Roger Ailes? Fox News, Ailes’s brainchild, is the news organization Stewart has most consistently complimented for its focus and skill. Over the years he has depicted Ailes as effective, “brilliant,” and evil. What made Ailes a visionary, Stewart thought, was his power to divine the most compelling narratives for his audience, regardless of what the mainstream media was focused on, and to then get the entire network on the same page.

Increasingly, Stewart wondered what it would look like to have a “Roger Ailes of veracity” — a network mind who was brilliant at producing high-caliber entertainment, but whose lodestar was not conservative politics but the most important practical issues confronting the country.

What Stewart had already achieved was to break open what media critic George W. S. Trow called “the context of no-context” — the way that you couldn’t understand why any story was covered on TV except that itwas on TV.

The O. J. Simpson trial, the Monica Lewinsky scandal, the Laci Peterson case, Crossfire: None of them made sense as events of public importance for a great people. But they made perfect sense as great television.

If you watched American Beauty and Fight Club and The Matrix in the Year of Peak News, you probably felt that getting beyond this empty culture meant burning it down and replacing it with something brave, real, and true. But implicitly, this meant that it would have the same unified audience, the same mass audience, freed at last from slavery to soulless garbage.

The catch is that the mass and the garbage were one. The reason TV culture was so shallow was that it imposed over everything what Trow called the “grid of two hundred million,” that is, the number of Americans when he was writing in 1980. The business imperative was to grab as much of the television audience — singular — as possible. All content decisions flowed from this imperative.

Jon Stewart did not get this. He dreamed of a broad, hard-working, underserved middle of the country, hungry for the entertaining veracity he would produce. The idealized audience he often invoked was the silent majority of fundamentally decent Americans who were turned off by political extremism and partisanship for the sake of partisanship. In a 2002 interview he called this the “disenfranchised center” for “fairness, common sense, and moderation.”

This might be a fair description of the 1999 broadcast TV audience, but it was not a description of Stewart’s own viewers. Pew Research found that The Daily Show had one of the most liberal audiences of any show on TV, beaten only by Rachel Maddow’s, and no show’s viewers skewed more high-income or high-education.

Roger Ailes did get this. The Fox News business model was not actually aimed at conservatives, but at newly deregulated cable. Ad-funded broadcast TV had rewarded achieving the biggest audiences possible. But cable rewarded having loyal, consistent audiences who would clamor for access to their favorite channels, giving owners leverage to negotiate the highest subscriber fees from cable providers. In 2021 Fox’s cable division generated $3.9 billion in revenue from fees and only $1.3 billion in advertising.

This business model meant cultivating ties with a particular niche, providing them content they would find enthralling, and eventually building identities around media brands. When Fox News launched, American conservatives were the biggest distinctly underserved niche. But MSNBC and CNN would eventually follow in their footsteps, for the same reasons.

As in so many other things, Stewart was also a master innovator of what he claimed not to want: building a devoted niche audience.

When the mass audience produced by advertising melted down, the innovations in style and production that Stewart had pioneered were a ready-made answer for this crisis. They provided a template for how to be successful not with a mass audience but with a loyal fragment — by replacing the culture of mass media with meta-commentary on it, and the costly production of original news reporting with an efficient repurposing of others’ work.

But even this description undersells what made The Daily Show unique, and why it seemed to wax even as all other TV news waned. The real audience that sustained him assembled where all audiences assemble today: online.

Stewart understood that converting a loyal audience into a media-business success is not just about getting eyeballs in front of the set (the Friends model), or even getting people to pay you every month (Patreon and Substack). It’s about getting people to be personally loyal to you, to identify with your brand.

You could tell that Stewart understood this because of the way he used clips of his own show. In legacy television, you would never give away your content in a way that couldn’t be directly monetized, from which you weren’t getting a licensing buck or a bump in the Nielsen ratings. But The Daily Show just gave their stuff away. They knew that the Internet would help build loyalty — and eventually an audience — that would make Stewart powerful.

The Daily Show was the first TV show whose clips regularly went viral via forwarded emails, discussion forums, and shared BitTorrent links. Even as The Daily Show often had to send its interns to archiving services to pick up physical tapes of other shows, it was one of the first to host specific shareable clips on its website, alongside full episodes. It was the first whose producers grasped how free clips online could drive, rather than cannibalize, viewership numbers. Stewart’s appearance on Crossfire may have been the first piece of national political journalism to go viral online. And all this got underway before YouTube, whose first video was uploaded six months after the Crossfire showdown.

The audience of The Daily Show, and eventually its offshoot The Colbert Report, was thus significantly larger than what the TV ratings alone revealed. It was more personally loyal to Stewart and Colbert. It was an audience that shared clips, talked about them on Twitter and Reddit, and bought books. It was an audience that crowdsourced rides and couchsurf spots to show up in the hundreds of thousands for their satirical “Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear” in 2010. It was an audience that donated over a million dollars to a Stewart and Colbert–organized Super PAC, as a bit. These shows did not have a passive television audience, but one activated and organized by, with, and through the Internet. As Colbert said of the Rally: “They were there to play a game along with us.”