An Interview with E. J. Koh

— feature

E. J. Koh is a poet, author and translator of Korean literature. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing and Literary Translation at Columbia University, New York. She is currently working on a childhood memoir, as well as her debut poetry collection.

Just a few years ago, after countless publications, she was named in Flavorwire’s list (at number two) of 23 People Who Will Make You Care About Poetry. We agree, and in this interview we hope you will see why.

Let’s start with how writing happened for you. Is it something you’ve always been interested in?

KohIt wasn’t writing and all that, it was the release. When I was a girl, I had terrible nightmares every night. My mother told me there was a curse upon the women of our family (for no reason I know). We could afford neither peace nor ignorance of our dreaming lives. At twelve or so, I figured out that if I wrote down the dream each morning, it wouldn’t haunt me the rest of the day.

So writing began as a tool in which I retrieved the pain inside my head and then tossed it into the wastebasket that is the page. Whether someone read them or not was beside the point then—I wouldn’t encounter creative writing, the type we all know and refer to, until my twenties.

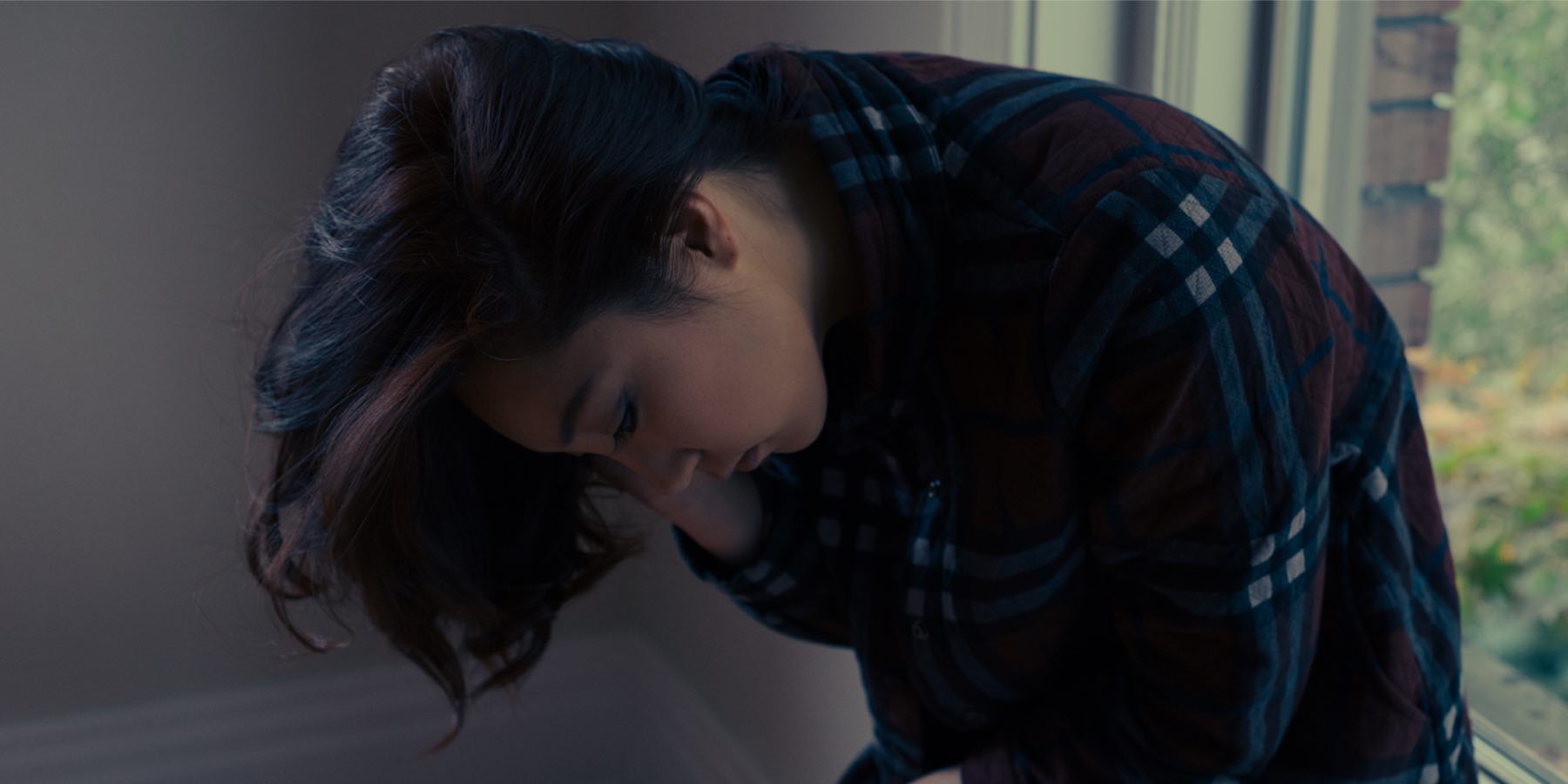

wildness

And was there a specific moment that you knew you wanted to pursue writing?

KohWhen my grandmother passed away. She raised me so my earliest memories were of her—how she scuffled forward, smelled like ginseng, and smiled with silver fillings. I wanted to remember these things. She would hoard plastic cups and forks. She would watch Japanese cooking shows. But she didn’t know how to cook. She was, to me, a subject that continued to reveal itself. I wanted to feel close to her even after she was gone, and a part of me felt, maybe if there was an afterlife, she would feel close to me too.

wildness

What would you say has affected your work the most?

KohGrowing up near Korean diasporic communities, I think, gave me this sick, brilliant sense of humor that comes from the back of pig-blood restaurants or the floor of a nude sauna. I was also raised with jeong, translated into a deep attachment, bond, and reciprocity for places, people, and things. Everything has meaning because I have jeong for it, and I was born of my parents’ jeong for me, and I fall in love with strangers because I have jeong for each of their unique, individual lives and experiences. I have jeong for the countries I left behind.

It’s a culture-specific word, but it is still an emotion I feel can be at least imagined. When jeong is betrayed, or forcibly removed, it results in an irreconcilable trauma—you may call that han. It returns to the philosophy that jeong is permanent, and therefore, never truly forgotten even when broken. I must answer the question, through writing, is such trauma worth the greatest heights of happiness, belonging, and love as possible in jeong?

wildness

What would you say to your younger self?

KohI would have said: exercise regularly, eat smartly, and drink water. Write letters to people who have been good to you. Send more flowers. Open the door more often, and tell people you appreciate them more times than you can keep track of. Stop drinking coffee, stop smoking, and enjoy life. My younger self was pretty sad, and she had real reasons to be, but she shouldn’t have let that dictate her life. She was impatient, easy to anger, and she expected too much from herself. The most I ask of myself now is to cheer someone up every day.

Yesterday, I wrote a love poem for my friends’ wedding gift—putting into words for them, their feelings for each other, and it reminded me of what I should feel towards everything in my life. With a lens of grace, kindness, and constant compassion (especially towards my own failures). We are precious to ourselves, and especially, to one another.

wildness

To that end, is there anyone who has influenced you along the way?

KohSusan E. Davis is this wonderful woman, the director of the writing program at the University of California, Irvine. I was introduced to her before I knew what creative writing was, and she took my hand, and took me to the heart of things. I would tell her, well, I was a child when I saw my mother jump out of the car. She would nod, touch her face, and say to me, what do you remember? I said, I remember the rosaries hanging from the rear view mirror. She would say, what do you know? I said, I know my dad stopped the car, picked her up, and brought her back alive.

I remember they were sorry to each other. But I don’t remember if they were sorry to me and my brother. She would say, Why should they be sorry to you? Because, I said, sometimes I think about jumping out of the car. And she said, because why? I said, because I want to understand why she did it, and if I get myself there, I could forgive her for it. Then what? I don’t know, I said. I just want her to be happy with her life so I could learn to be happy with mine. She said, then what is the poem about? I guess it’s not about the car, I said. I guess it’s about how much I would have done to break her fall, to use my own body to save her, to save myself.

wildness

And how about friends and family, do they support your work?

KohNot always, not every day, but in general, the answer is yes. They believe in what I do. They believe that what I do is important to me, and they believe that what I do is something only I can do. But, do they support it? Not all the time because they are supportive in so far as much as they don’t see me struggle. And they, more than anyone, have seen me struggle. They grieve seeing me put myself through these trials of writing, testing, waiting, writing, and the emotional wrestling of the lifestyle. They believe in me, but, they want me to be happier more often than not. With writing unfortunately, that is not always the case. It is something I have to answer for every day and ask myself, must I continue?

wildness

Is location important to you? Does it affect the work you do?

KohIn Seoul, I wrote at a Tom N Toms coffee shop alongside a busy street in Pundang. I liked people watching and noisy conversations. I liked to overhear someone talk about a great piece of information they heard and how it must be true. In New York, I worked at a tiny shop called Kuro Kuma near 125th. They weren’t friendly but I went back for the almond croissants four days a week. In LA, I wrote in Little Tokyo preferably near a Bearded Papa’s for cream puffs. Orange County, I ducked into a Starbucks and ordered a disgusting pile of whip cream, which I loved.

In San Francisco, I jotted things down at the Legion of Honor museum once. In San Jose, I dropped by the Great Mall food court so I can eat the Cajun chicken over rice. In Seattle, now I observe architectural cafes, but I’m most comfortable at Firehouse Coffee by the locks. In all this, the location impacts what I eat, what I hear, but no matter how hard I try, it does not determine my level of creativity or productivity. That depends on the gods.

wildness

How important is a creative community to you?

KohI depend on my creative community. When I came to Seattle, the Kundiman poets introduced me to the local writing center, universities, and journals. Editors from the James Franco Review and The Seattle Review of Books have not only been interested in my work, but curious about the work of my colleagues. The camaraderie is very rich and unburdening.

Whereas, in New York, I pressured myself to attend the readings, events, and panels. I wanted to know every gossip and project. Now I can say “no.” I will try to go, but if I can’t, that’s okay. Knowing the community is there and nearby is enough. You don’t have to be best friends with everyone. They understand and they don’t hold it against you because, you know, they’re writers too.

wildness

Could you tell us what a typical day looks like for you?

KohIn the morning, I mentally organize what I will accomplish for the day and why I must do these things. I cut it down to three tasks “for quality purposes.” I started fasting one day a week, but otherwise I eat eggs or oranges. I knock one thing off my list—it might be a few e‑mails, or I might have to speak to an inquisitive parent.

One time I was nearly confronted by an adult’s therapist who feared that my writing exercises did not address their patient’s needs. Then, I head to the dojo for jiu jitsu training, or I might try the rock climbing gym. In the afternoon, I teach workshops either in the city or mentor youth students in the library. I knock off two last things on my list—maybe it’s an interview as this, or edits to a couple pages of writing. I end my day journaling, but only for a few minutes.

These days, I’m not thinking about working as hard as I used to. I’m thinking about doing things that make me happy (and in a manner that pleases me). Something I’ve changed recently is that I reward my efforts, and not the outcome. I don’t celebrate that I’ve achieved something, but that I’ve tried. I learned a little later than others that I must be kind to others as I am to myself.

wildness

Would you mind telling us what you’re working on at the moment?

KohI’m working on a childhood memoir with my agent Kate. It takes place from the time I was fourteen and my parents left the country but I remained behind to complete my education. Because it’s a creative non-fiction piece, it also has letters that my mother used to write me during that time, describing her days to me in a language I could not understand. I translated them and set them side by side with the events of my darker childhood, searching for a place to belong, and honestly, a pair of open arms.

But the past few months, I fell into a deluge of ceasing to write altogether. Writing became something I couldn’t live without, and thus, sacrificed relationships and life events for. It hurt me physically, mentally to continue writing as much as it did to stop it altogether. But there was a sensational outpour of support around me. Colleagues from The MacDowell Colony called to make sure I was okay. Complete strangers wrote to me every day. I also came to know an audience I did not know I had. They would e-mail me, “Don’t quit, if you must, I understand, but don’t. I’ve been reading you for years and I never mentioned it. But you shouldn’t give up.” It was profound.

Authors, and especially poets, don’t really know who’s out there. They don’t get enough support, not from others and not from each other, but it’s important to remain human, connected and compassionate. It’s not easy being an artist, and it never has been. If there’s an artist you like, send them a little note. There’s never enough that you can do for their spirit. For me, it gave me courage to find balance, pursue writing peacefully, steadily while maintaining the rest of my life. I am still working on it, but I don’t know if I could have gotten this far on my own.

wildness

So, are you creatively satisfied? Is there more you want to achieve?

KohMy younger self would’ve answered “never.” But, I want to remain in a constant state of being creatively satisfied. I want to be creatively satisfied simply by sitting down to write—the opportunity which isn’t afforded to everyone. I want to be satisfied knowing that whatever I write might be the last thing I write, or whatever I publish might be the last thing people read. Otherwise, my motivations will take a darker, more sinister tone, which isn’t exactly healthy as proven in my field. If the statistics in 1990’s were that 20% of poets will take their life, today that statistic has exponentially grown.

I will say, there are things I want to work towards but with lesser ambition: I’m working on a novel addressing suicide and I’ve completed a book of poems I hope to publish soon. But, if I never get to these things, I am still creatively satisfied. I am okay with what I have. I work towards these things only because I feel fortunate to get the chance.

wildness

Finally, what legacy, if any, do you want to leave?

KohI think, oftentimes, writers want to be remember for their work. But, if I were honest, I want to be remembered for the way I was in person—the way I remember my grandmother. She was always listening. She was funny, witty, and she offered perspectives that fell under the grey area. She argued against what might be right or wrong, black or white, and in this, she made room for different emotions people felt, experiences they went through, or judgments they have come to believe. She was a compassionate woman who never wrote a poem or a book. She didn’t have to. Because she had her family, her children, her grandchildren, and her friends. I want to be remembered, not for my literary devices, my voice, my posture behind a podium, but for having loved deeply.

Read more from Issue No. 1 or share on Twitter.