An Interview with Inua Ellams

— feature

For anyone who doesn’t know, would you mind talking a little bit about your creative journey?

EllamsWhen I was a kid I wanted to be a painter but at some point I got disillusioned with it. I thought visual artists were a little too pretentious so considered working as a graphic designer, which I thought of as functional visual art. I applied to go to university in Dublin to study that, but unfortunately we had to leave Dublin and return to London. In London I could not afford university or art materials for that matter, so I began writing poetry. I thought of it as painting pictures with words. At first I worked in the performance poetry world, at some point became disillusioned with it and began writing longer poems for stage which I could perform myself. These became my one-man theatrical shows. I moved on to writing for others, longer poems to be performed by groups of people and that led to writing and creating plays for theatre. I now work as a poet, both for the stage and page, and as a playwright for radio, stage and screen, and still continue to create and perform one-man shows.

Alongside this, I began working as a graphic designer. I taught myself the basics really—I spent a lot of time in libraries trying to figure out elements of style and how they related to my creative journey. I work predominantly using pencil and paper, and illustrator and Photoshop, to create advertising campaigns or illustrations, mostly for my stage productions but also for a handful of friends and selected clients.

I also started something called The Midnight Run in 2005. The Midnight Run is really just an environment for conversation, where we invite strangers to explore a city’s streets from 6pm to 6am, or 6pm to midnight. We also invite local artists to run workshops during the course of the run. We walk-explore, who we are, where we’ve come from and how identity, space, place, narrative and destiny affect the decisions we make. The workshops designed by the artists I invite are created to inspire honest conversations between the strangers or participants. It’s become an international project now, the last one was in Perth, Australia. We have plans to hold events in Melbourne, Australia, Prato, Italy, and a few in England, in Canterbury, Peterborough and perhaps, a few in London towards the end of the year.

So, those are the things I do: I’m a poet, a playwright, a performer, a graphic designer and illustrator, and a midnight runner.

wildness

You’ve worked in many fields over the years, how do you know which form is right for a particular project? Related to that, how does your preparation differ between forms?

EllamsI don’t know at the onset of a project or when I begin speaking with theatres or even when I’m commissioned to create work. I make it known that I’m not sure what I’m going to create. It could be a series of poems, a monologue, a play-in-verse or a somewhat traditional play. What I usually wait for is something to settle, for some sort of a sign. Sometimes I have ideas that have been tinkling in the back of my mind which suddenly come to the forefront, and I think ‘this is the time for it’ or, something will happen to indicate that this is the time for an idea. I believe a lot in destiny, in faith, in happenstance, in serendipity, in synergy, and things tend to coagulate around a certain time and an idea will rise to the surface. So, I never know really and in the process of writing, ideas may change as well.

I have a play opening imminently at the National Theatre which I initially wanted to be a poetry and visual arts project set in a barber shop, but I failed to secure funding for it. The idea stayed with me until I realised how much bigger it could be, and it has become the biggest thing I’ve written, for a cast of twelve, set in seven different barber shops across the world.

When it’s poetry it’s just me at a desk, and most of the time this is it. I may have to go out to interview people if it’s a project that requires such a process, but more often than not, I’m sat at a desk, reviewing, editing, sharpening poems. A theatre project requires more people, everyone from my producer, to the actors—I rely on them for information, for suggestions, for feedback—to the directors. They are the motherships of projects and even elements of marketing can affect the decisions I make in the script. I wonder what inroads I can write into scenes to make a project saleable… what hooks might be needed. I tend to bring those things out in subsequent drafts to make sure those who are selling the project have an angle, have something they can talk about.

wildness

Is it these differences that drive you to experiment with form?

EllamsNo, I experiment with form because it’s something I always have ever since I started working as an artist. I started when I was nineteen and I’ve always experimented with form. For me it’s linked to my fascination with the foundation of hip hop culture and it’s idea of creating something out of nothing, which requires collaboration, it’s also, I think, plugged into my Nigerianhood, into the idea of community, into sharing.

There’s this great folk story I remember being told when I was a kid called “Stone Soup”. It tells of how, when a small village had run out of produce for each household to create meals, a wise man got a huge pot and placed a stone inside. He said, “this is all we have to make soup,” that he would stir it until something came forth. Members of the village gathered around the empty pot and began to think, “there’s just a stone here, I have a few potatoes in my kitchen, that might help.” Someone else would come and say, “I have some spice,” another would say, “I have this old crusty leg of lamb,” and so, together, they created a broth and all the villagers ate well.

Collaboration and the cross-pollination of ideas drives the idea of experimentation for me.

wildness

You have spoken of your varied influences previously—classical and hip hop music, your Muslim and Christian upbringing—but how do you allow each facet of yourself the room to breathe within your work?

EllamsFor me, the classical elements of hip hop music specifically relate to lyricism and poetry. The braggadocio culture which exists in hip hop is linked to masculinity and to race. These elements are constantly beneath the surface of my consciousness, they are always buffering and pushing things to the surface. I’ve learnt to not restrict them because they can create really interesting standpoints and clearer lenses through which I can see the things I create. And in the editing, in the filtering, is where I realise exactly what they are or what they are steering me towards. Sometimes problematic material appears but I can use that to create empathy with an audience. If I create a character who owns these flaws but also has other qualities, then we can see the three-dimensionality of humanity, and that is what I always strive for in my work.

For me this is underlined by the fact that I came from a multi-faith household. I was always questioning and looking for common denominators, for the through lines through humanity, to show our complexities. We are contradictory creations; we reveal ourselves in conversations with each other, amongst friends, with how we arrive at opinions—those arrivals are at the end of tumultuous journeys. Over the course of my life I have tried to uncover gems, going into caves and finding little diamonds, little nuggets that shine light across the years. And ultimately, I think that’s what I try to create, beautiful things out of confusion.

wildness

Similarly, do you feel it is important for an artist to incorporate these autobiographical elements in their work?

EllamsYes, I think so. There’s a poet called Lebo Mashile, a friend of mine, a South African poet, who says that “the work of being an artist is intimately linked with the work of personal development.” I think it’s the only way we can make sense of ourselves and bring an endless and boundless humanity to the things we create. When we write, however distant we think the work we create is from who we are, in its depth, there is a seed, and that seed is the kernel of humanity, an autobiographical humanity that’s an element of the work. I think that is what draws an audience to a show, that’s what underlies everything, the emotions. It’s how an artist makes them feel, which is ultimately how we feel in the creative process of the work.

wildness

In a previous interview you mentioned that you had recently “discovered about [your] identity—or lack of it.” Would you mind elaborating on this?

EllamsI left Nigeria when I was twelve years old and lived in Europe until I returned in 2012, so a considerable amount of time had passed. When I lived in England I definitely wasn’t English enough for my contemporaries, for my classmates, and when I moved to Dublin I definitely wasn’t Irish enough. So all I had, all I thought I had, was my Nigerian identity, but when I visited Nigeria in 2012 I realised that I definitely wasn’t Nigerian enough either.

There wasn’t a place I spiritually or culturally belonged. I felt like I had lacked a clear or specific identity, and what I’ve enjoyed since is discovering the way these three countries I belong to kind of criss-cross, where they cross-hatch and create the light and dark in my cultural foundation. I shine lights through those cross-hatchings, through those meshes of identity and history and stories, and what is projected on the other side is akin to shadow puppetry.

wildness

You founded the Situationists’ inspired The Midnight Run over a decade ago, how has it changed since then?

EllamsIt started with a friend and I simply walking through London. That was the first, unofficial, Midnight Run, something we did for fun. I then began inviting members of my newsletter to come and spend evenings with me wandering through the streets, writing poetry. At that time I was the focal point of the experiences and the only art form celebrated was poetry. I later realised a lot of my friends were artists and there were elements of their craft that they could easily share with an audience, so I invited them to run workshops. I expanded the idea to include anyone who did anything that was interesting and interactive, anything that could work portably and could work in cities, in the outdoor spaces we found, and so in 2015 I trained five other artists on how to deliver runs.

Over the years we’ve had everything from Tai Chi instructors to basketball coaches, to guerrilla gardeners and Greek wrestling enthusiasts, to puppetry, poetry and political speech writing, as well as cookery classes. It’s vast. In Perth, were the last Midnight Run was held, a guy printed forty flutes with 3D printers and we created a flute orchestra right outside the Perth Conservatoire. It was beautiful and magical. That’s how much it has changed, how much it has grown.

wildness

What motivates you to continue?

EllamsThe people… the joy of each night. I know it’s been a good Midnight Run if my cheeks are hurting from laughing too much and that’s happened in each run; meeting people, spending time with them, the idea of control and release. Things never go exactly to plan, but that becomes part of the experience. I’ll often ask participants to lead sections of the run if they know how to get from one location to another. Again, it confirms humanity and symbolizes what it means to live in a city. It deconstructs so many of the reasons we create barriers between people, whether socio-economic or language, all of that stuff dematerialises during a run, all you have is who you are and what’s in your backpack; which tends to be food that we share. That’s what motivates me.

wildness

The Midnight Run’s ethos—‘It’s About People and Places, Art and Artistic Engagement.’—makes it obvious, but how important is the artistic community?

EllamsI’m going to quote Star Trek, artists “boldly go where no-one has gone before.” They are gateways to our truer selves, and they often affect change in startling, simple ways. For me, it is infinitely important to deconstruct and play and create memories with different groups of people. It sits somewhere in the realms of religion for me, it is that holy yet very grounding. Quite a few artists who have taken part in Midnight Runs laugh that they are being paid to do it, and some have refused to take the payments offered and have asked me to donate the fees to charities. They just didn’t see it as work, they saw it as play, with a ready, willing and giving audience.

wildness

And, similarly, how important is immersing yourself in the local environment, to you?

EllamsThe nation tribe I belong to in northern Nigeria are the Hausa people. They were natural nomads who foraged and travelled with herds of cattle, trying to take care of their environment and celebrate it as best they could; to be caretakers of the land and to be nourished by it. That sense of exploration, to go out with as little as possible and survive… requires one to be aware of one’s surroundings and I feel like it is in my blood to do so.

wildness

What does a typical day (if there is such a thing) look like for you?

EllamsI don’t really have a typical day. I usually go to bed around 1 or 2, and try and wake up around 6 or 7. I try not to look at my phone or get pulled into the Twitter-sphere to see what’s happening in America or the rest of the world. I get up, look at emails between 11 and 12, and then write as much as possible. I might check emails again between 3 and 4, but then write as much as possible until the end of the day. But that’s on days when I’m trying to write at my desk, otherwise there could be interviews, workshops I’m running, I could be in a studio or a theatre. I don’t really have a structured day—it’s a little chaotic if I’m honest.

wildness

Would you say that you’re creatively satisfied?

EllamsFor the moment I think so. For the most part I’m doing what I’d like to do, in the ways I’d like to do them. And I’m able to live off of my creative endeavours which not many artists can—I’ve been a self-employed artist since I was nineteen and I’ve been completely spoilt by the places I’ve worked, by how I’ve been embraced for my work, and championed. So I’m creatively satisfied at this moment. There are things that I’m longing to do, bigger, more complicated and complex projects. But you know, there’s nothing more powerful, as Victor Hugo says, than an idea whose time has yet to come. And I think those times will come but at the moment I’m satisfied, my plate is full, my cup runneth over.

wildness

Related to that, what are you working on at the moment? Do you find yourself constantly torn between projects?

Ellams

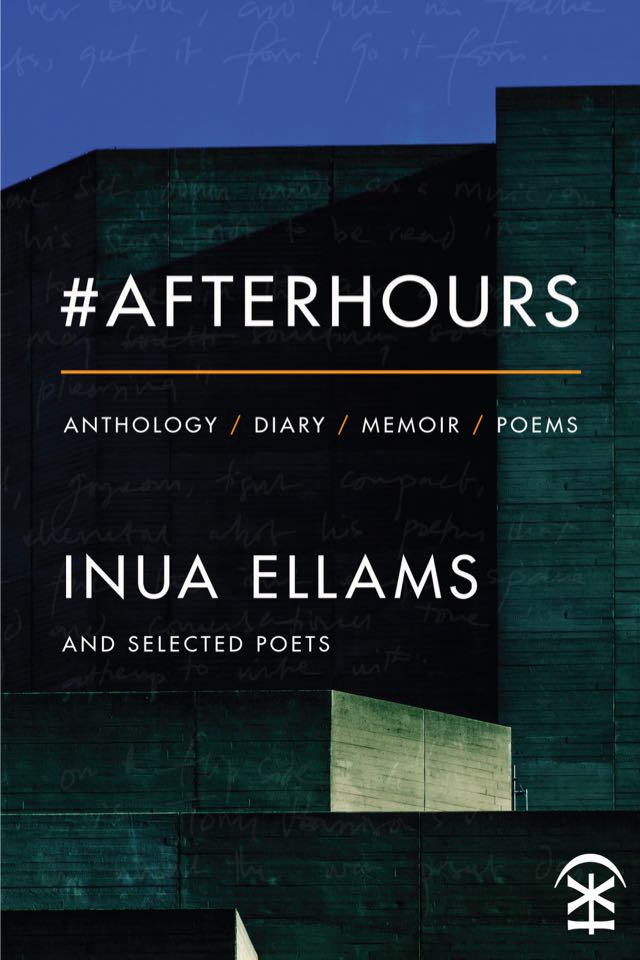

I am constantly torn between projects. At the moment I’m working on a play called Barber Shop Chronicles, which opens at the National Theatre in June. My book launch is today [12th April], and it’s a book called #Afterhours, which I wrote about a year and a half ago. After that there are a couple of plays I’m working on for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Tricycle Theatre. Also a series I have written for the BBC, we haven’t figured out what we’re going to do with it but it’s complete.

I’m going to dive back into poetry and step away from theatre for a little bit, perhaps consider bigger screen projects (for television and film). I also have ideas to do with a novel and a play adaptation for film. But, right now, Barber Shop Chronicles, #Afterhours, and The Half-God of Rainfall, a play I wrote for the Tricycle, are the three things I’m spinning.

wildness

Finally, what are you reading at the moment? Who would you recommend?

EllamsI’m reading the various poetry magazines I’m subscribed to; which is The Poetry Review here in the UK, and Poetry magazine from the States. I’m reading back issues really. I also have a ton of books that I’ve purchased, most of them poetry books, some by friends of mine, which I just haven’t had the time to read. I’m ploughing through them.

In terms of fiction, the next thing I’m going to read is The Great Gatsby, I’m trying to guess what the films might look like before watching them. It’s really an experiment in imagination, to see what decisions I would make if I were to adapt the story, then watch how they were adapted. There are two different versions, one with Leonardo DiCaprio and the other with Warren Beatty.

After that I think I’ll read Welcome to Lagos, a novel be Chibundu Onuzo, a friend of mine and a great writer.

Read more from Issue No. 10 or share on Twitter.