Ají Dulce

— Fred Arroyo

for Pablo Medina

A stallion and three mares trotted in a field of red dirt. Clumps of tall grasses grew along the field’s edges. The stallion began galloping back and forth across the field, dust rising in clouds over his legs, and with each turn back he circled the mares into a tighter group. His eyes were black frantic pools, and his long mane shook every time he nickered and nudged the mares’ necks and backs. He slowed next to a dark brown mare, nibbled her neck, and grabbed her mane with his teeth and pulled her away from the others. Their bodies were lean and muscular, their coats smooth and shiny. The stallion reared up, whinnied, and when his front hooves touched the ground he dragged them through the dirt. His nose nudged the mare’s rump several times, and the black wrinkly sack between his legs started to stretch, grew and grew in size, and to my young boy’s eyes the stallion’s member grew at least two feet, hard and sharp below his stomach and pointed towards the red dirt. His eyes widened even more, he mounted the mare and bit down on her neck, as she slowly stretched it and dropped her nose, her eyes just as wide and dark and frantic as the stallion’s.

Wepa … Dale … Asi, chico, asi … rose in a loud chorus from the edge of the field, followed by hearty laughter. A group of men were sitting underneath a grove of flamboyant trees. Some of them wore white hard hats, telephone company workers raising new poles and connecting lines. The other men seemed like friends in nice pants and guayaberas. They all sat on small stools and crates eating from paper plates, the ground sparking with the flaming blossoms from the trees, as they watched the horses in the field.

See how they play, my father asked. He giggled, his cheeks red. I felt blood rise to the edge of my ears. I tried to smile back but my jaw trembled. The stallion whinnied again, and rocked against the mare’s rump. Asi, chico …. And the laughter rose again.

My father walked down the road. We were waiting for a carro publico. When I turned back, all four horses were bunched together nibbling on the long grass. Their figures were broken and cubed, as if they shared the same legs or necks, the barbwire fence and red dirt breaking their bodies into fragments and impressions. There was such a mix of red I’d never seen before—the red dirt, the reddish brown horses, the brassy gold glinting in the stallion’s mane mixing with the tawny brown of the mare’s. Their eyes shining with dust. The wind picked up, the crimson blossoms on the shaking flamboyant drifting in the air, and I noticed for the first time the long stalks of sugar cane in the backside of the field, and farther back the mountains looking down in dark green.

I will often find myself walking in a field surrounded by swaying trees. There’ll be the scent of eucalyptus or pine. A hawk in the high blue sky drifting on invisible currents. The strong smell of hot dust or manure, perhaps the faint aroma of the sea. Even if the field is empty, I see horses running, red dust powdering their hooves and legs, the wind stirring the hair on their stretched necks.

The fall to the soil of a plump mango from a heavy afternoon rain, the birth of a clear azure sky broken by torn, puffy clouds, the sky sparkling on the red dirt road, and then a young boy with no shirt, his skin a little darker than the dirt, his jeans streaked with dust all the way down to his bare feet, and when he pulls the hemp bridle he and a sorrel horse gently trot by, the boy’s hair slick and still, the horse’s neck taut, its blond mane fluttering with el brisa de la mar.

I write these words, step back into that January afternoon, and song gallops across the fields of memory:

That night in January

who did you go see,

like a colt chomping at his bit?

And my desire bites through, and, with blood in my mouth, I spit it out into the dust.

When we finally made it up the mountain that I dreamed of crossing day after day, it was as if nothing happened. My father and the men followed a thin red path that darkened with shadows, the trees and bamboo creating an arch over the path. The air cooled as if we were walking towards ice. They stopped. Looked: we stood in front of the mountain, and falling from its slope was a silver stream that gathered into a pool bounded by black boulders, green and yellow leaves floating on its surface like boats seen from a great distance. My father broke off a wide palm from a wild banana tree, crossed from boulder to boulder, and stuck the palm into the mountain’s face, water tumbling in a silver and white curtain into the pool, the bamboo leaning in.

It was cool and shaded here, the mountain blocking half the sky, the jungle seeming to swallow the other half. Up through the treetops there were jagged holes through the thick leaves and the sky. The men—my father, my uncle Ismael, and a distant cousin—undressed. They waded into the pool, plunged down holding their noses, slowly fell forward and under. Water splashing and raining from the men, the tumbling stream. Someone had brought a bar of soap. My father lathered up, stood on a boulder underneath the palm he had placed in the stream, and let the water shower on his body until it was clear and his skin gleamed. The men laughed, splashed each other, dove into the pool, rose, white foamy circles forming underneath the stream tumbling into the pool. These were men that had worked hard since a young age, and they were lean and graceful and smooth, arms roped with muscles, their stomachs firm, and they held their brown bodies straight and tall. My uncle soaped his thighs, scrubbed his stomach, his hands quickly rising and rubbing under his arms. My father was the whitest, and though his arms and legs and chest were brown, his buttocks and the top of his thighs were like snow. He called me in.

I was fat, too conscious of what I might look like naked, and so I undressed slowly. Without taking my underwear off, I stepped in, the water colder and clearer than any I had ever encountered. I went under. I saw the men’s legs flash by, tiny pink shrimps schooled together and lit by the weak cloudy light falling through, and on the surface of the pool the undersides of the small boat-like leaves that floated on small silver-green waves. When I came up I heard Ismael singing a sad and beautiful bolero, his voice sounding so clear in the spaces he found in between the silence and the tumbling stream. Just like the men I soaped up my body, stood underneath the stream, and left my eyes open so I could see them through all the falling water. This was the mountain I wanted more than anything to cross. Here it was crossing me, bathing me, and that had to be enough. There was nothing else to ask for or remember. I cupped the pool in my hands, clouds and silver sky reflected within, and tasted for the first time agua dulce. My father and his brother stood side by side, up to their knees in the pool, their shoulders touching. White next to dark brown, their black mustaches glistened with drops of water, their smiles, the red in their cheeks and their clear bright eyes—there was a love between them I didn’t know. It is only now, morning after morning, when I listen to the water falling behind them, look closely at their young faces, that I begin to discover words that take me between shadow and dream, take me to a pool of life where I can touch them just as surely as my hand touches my stomach, warm, hard, wet with yesterday.

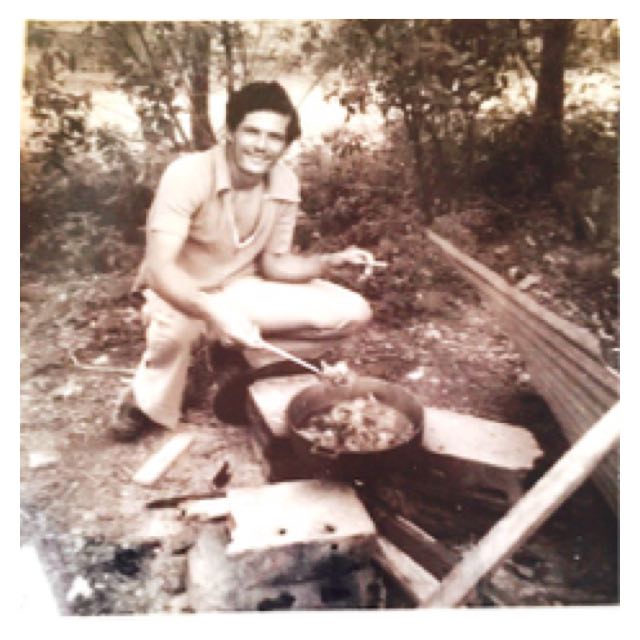

Here is a photograph I took of my father’s brother, my uncle Ismael.

Such an elegant moment, even in all its broken and cobbled together simplicity. Ismael’s slacks, his open collared shirt, the drape of his arm and the cigarette in his hand. The faint rise of a vein running along the inside of his arm. His smile. There’s only a fragmented, poor life here—broken concrete blocks, scraps of wood, twigs and leaves, a jagged piece of corrugated tin. But just on the other side of the road, where Ismael gazes, I can find all of them as a part of my abuela and abuelo’s house. And even in the silence of this photograph I hear his song.

All the men in my father’s family are handsome, and anyone can clearly see this in my uncle’s face: his dark eyes happy with rum and his cooking, his smile, and the perfection of his arms and hands, the pointed cigarette, the silver spoon. Ismael. He’s cooking a goat or chicken stew with big chunks of yuca and ñame and potatoes and a sauce from lard colored by achiote seeds that browns the pieces of meat a rich saffron. There’s garlic, onion, cilantro, oregano, and several green, yellow, and orange ají dulce peppers. He stirs in a small can of salsa de tomate. There’s the sharp sound of the silver spoon striking the lip of the aluminum pot so all the pieces, juices, and flavors fall back inside, and there’s the scrape of the spoon along the bottom so nothing burns over the wood fire. We eat the steaming stew in bowls with white rice. It is a windy day. Even though the photo is in black and white, I see there’s an overcast sky, and Ismael has the piece of tin leaning and propped up with a board next to the fire to block the wind. I don’t remember if he cooked the stew before or after our swim. There, under the mango tree, I shiver and let the smoke and the fire, the smell and the flavors, run warmly along my arms, that’s what I remember. Ismael, I call, raise my silver and black camera, and press the button over my eye.

Read more from Issue No. 12 or share on Twitter.