An Interview with Prabda Yoon

— feature

For those who don’t know, you’re a writer, film-maker, painter and visual artist from Thailand. Would you mind talking a little about your creative journey?

YoonTo some people, it may seem unusual that I’m doing so many different things, but to me it feels completely natural. I started writing stories when I was around 10, got my first short story published in a magazine at 13. As a kid, I was always drawing, making zines, reading, watching films, writing song lyrics and poems, designing imaginary posters. I decided to go to art school because by the time I was finishing high school I was very much into painting and photography. For my senior year project, I made experimental animations, and my first job after college was graphic design. I was always doing different creative works and it never occurred to me that I would have to chose just one thing. I think of myself as a visual artist who happens to enjoy writing, even though I’m known, at least in Thailand, as a writer more than anything else. And it is true that I write more than make visual art. So when people ask, I say I’m a storyteller. Some stories are told with written words, some with moving images, some with shapes and colors, etc.

You lived in the US for several years studying art, what impact has that experience had on your writing?

YoonMany of my early literary ideas came from my interest in the works of the visual or conceptual artists I appreciated, people like Marcel Duchamp, Isamu Noguchi, Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, John Cage, Jean Arp, Hans Richter, and many more. While studying art in New York City, I wrote some stories, and for me they were more like conceptual art pieces. So art did have a big impact on the way I thought about literature. It was also in art school that I took a course on James Joyce. I think I feel more like an artist than a writer even now.

wildness

Do you think feeling like an artist creates an interesting dynamic in your work? Does it inform the way you structure your narrative?

YoonI think feeling more like an artist means that I prefer not to use only writing as my creative medium. I’m not the kind of writer who can’t live without writing. If one day, for some reason, I could no longer write, but the other artistic practices were still available to me, I would be content with that and not miss writing so much.

I guess the fact that I see writing as an artistic practice interchangeable with design or painting or sculpture or film or music also informs the way I lay the foundation of my storytelling, particularly how I tend to focus largely on ideas and attitudes rather than character development and the other features that are supposed to be of high literary value. I get bored quickly with common dramatic themes and characters that resemble real life and real people. Of course, when I create my characters and situations I want them to feel real and engaging, but I’m not interested in spending time and words describing scenes in detail or show the particulars of my characters or build a complete literary human being or something like that. Big literary works that feel like meticulously constructed worlds are certainly impressive, and they’re definitely works of art, but I have neither the talent nor the interest to compose such a work. I’m more inspired by ideas and moments.

wildness

You’ve discussed the difficulty of translating English to Thai (and vice-versa), could you talk a little about your process? How have your translations of Nabokov and Salinger been received in Thailand?

YoonI only know two languages well enough to have some opinion on translating literature, but I think that each language has a kind of ineffable uniqueness that’s very difficult or impossible to duplicate, and translation is, in a sense, a reconstruction of something with different materials. You can make it feel very close to the original but in the end it’s something new. For me, when I read a book, especially fiction, the thing that’s important is the “voice” or “attitude” that comes through the prose, and when I translate a book I try to find a similar voice or attitude in the language I’m translating it to, rather than to concentrate on achieving a kind of word for word solution. There is no exact replica of Humbert Humbert in Thailand, so what I can do is to try my best at looking for a close imitation. The same is even truer with Holden Caulfield.

My translations of Nabokov (Lolita and Pnin) and Salinger (all of his published books) have been generally well received, I guess, at least by the readers. Some of them have been reprinted several times. But I have not heard anything from the literary translation community. I suspect that some professional translators consider me an amateur, which is of course correct.

What was the experience of having your own stories translated into English like? Were you tempted to work on the translations yourself?

YoonI’m grateful for Mui Poopoksakul’s translations of my work. It’s because of her that some of my stories are reaching English readers. The relationship between Mui and I was very simple. She contacted me about translating a book of mine for her thesis, I said sure. A while later she showed me some drafts, and a while after that she sent me the news that an independent publisher in the UK wanted to publish the book. It was all absolutely effortless on my part.

I vaguely remember thinking about translating my own work into English, but it was more like, oh, I’ll do it when I have nothing else to do, and that, fortunately, never happened before Mui came along.

wildness

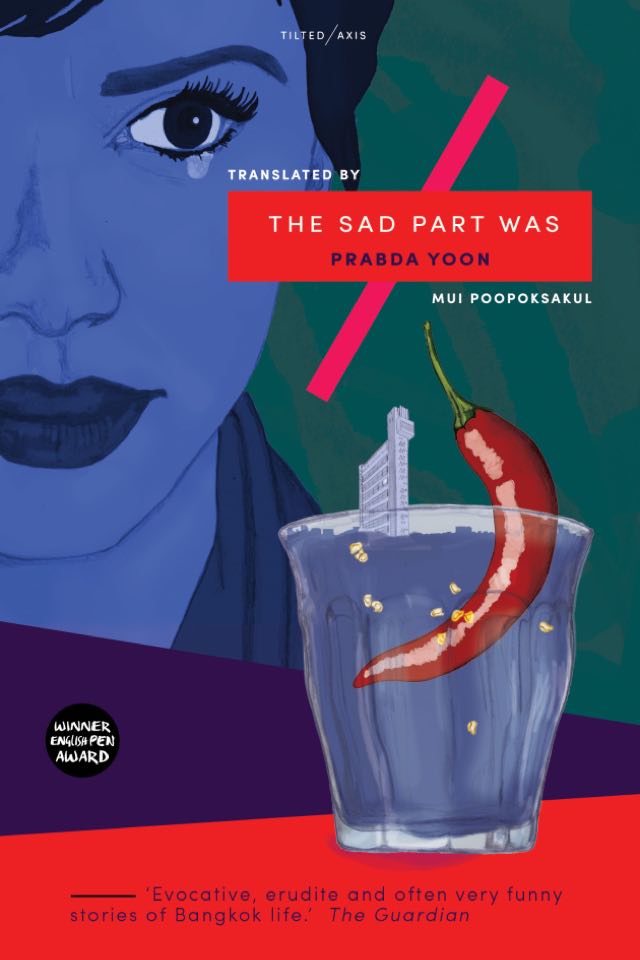

The Sad Part Was has received multiple glowing reviews—with BuzzFeed Books calling your writing “Highly literary”. How has this positive reaction affected your thoughts on your other work being translated?

YoonI was of course thrilled about the positive reviews. Again, the compliments should go to Mui Poopoksakul. She has just finished her translation of my next story collection. I have full confidence in her. The Sad Part Was is currently being translated into Chinese and an Italian translation is supposed to be on the way. Those will be impossible for me to judge, but it’s exciting nonetheless. However, I don’t worry too much about any translation of my work, to be honest. I’m more concerned with the works at hand.

wildness

In 2016 you directed your first movie, Motel Mist—what was the experience of directing like for you? How did it feel to bring your own words to life visually?

YoonTo my surprise, I enjoy the experience of being on the film set immensely. I like the confrontational and unpredictable nature of the process. Strangely, to me it feels similar to painting, in that each brush stroke is never something one can plan exactly, which is the beauty of it. A film shoot is very fragile. You have all these factors that could go wrong at any moment. A lot of times, you have to improvise, and when the improvisation turns out better than anything you could have planned or imagined, it feels amazing. At the end of each day, you can’t believe you’ve survived. It’s a bit different with writing. Yes, there’s space for improvisation in writing too, but there’s also the delete key and the trashcan. One has more control in writing.

I don’t see my film work as an extension of my literary work, so I don’t feel that my films are visualizations of my words. When I start to work on a film I do it with a different mindset. Film is more like sculpture, and I want to get the writing part over with as soon as possible so I can start to knead the clay. Writing is closer to thinking, it doesn’t have to turn into anything else.

wildness

The film was pulled from Thai cinemas during the country’s recent year of mourning. As you’ve discussed freedom of expression previously, how did this situation impact you personally?

YoonThe decision to pull Motel Mist from the cinemas was an act of panic and self-censorship. The film received the 18+ rating from the censorship board, so it was absolutely fine to screen it. The only person who was not fine with it was someone in the company that gave us the money to make the film. It was personal. It had nothing to do with issues of freedom of expression, and I don’t think anybody would’ve objected to the film in regards to the mourning period. The film received the 18+ rating because of some sexually explicit scenes, which were very minor in comparison to sexually explicit contents in so many other films and media that one could find around the same time.

But this incident did reflect that in Thailand certain subjects could make people very nervous and fearful. I always say you cannot yet be a liberal person in Thailand officially, because you can’t express your liberal principles and feel safe about it. You can be liberal in private or sometimes even among friends who don’t necessarily share your views, but there are so many conservative social conventions and formalities that shape the Thai public life and if you show that you prefer not to comply, you’re taking a serious risk. This is something that frustrates me profoundly about working in Thailand.

wildness

Related to that, do you think that a liberation movement will eventually be possible in Thailand—are the youth movements seen as a legitimate call by the public or disregarded completely?

YoonAny kind of movement, if driven by openly liberal principles, will still have a hard time succeeding in Thailand. It may take a couple of decades for any significant change to take place. But by that time the world will have changed significantly, and Thailand will have been affected by it too, so it’s really quite difficult to foresee. No one predicted the popularity of Facebook or Twitter, who knows what we’ll have in 20 years. Something new could suddenly appear and help to accelerate a shift towards liberation. That’s the optimist’s view, but you’re talking to a pessimist.

wildness

How important is it to immerse yourself in the local community?

YoonI have been called elusive by some colleagues, and I think it’s a fair description of my personality. I’m usually the one that strays from the group. But I think I try, in my own way, to engage in certain aspects of the local creative community, up to a point where it doesn’t feel like an obligation. What drives me to make art, generally, is the feeling of being an outsider or outcast. It’s something I can’t seem to change about myself, but since I want to be in an artistically exciting environment I realize that some participation or initiation on my part is necessary.

wildness

What does a typical day (if there is such a thing) look like for you?

YoonI go to sleep quite late, so my day usually begins around 10 or 11 a.m. I must have at least 2 cups of coffee, then what happens next depends on the work I’m doing. I’m not a disciplined writer and I have no work routine. I prefer to write in the afternoon, after those 2 cups, when I feel most awake. I surf the internet in the evening, searching for inspiration or just reading articles. I read a book or watch something before going to bed. When I’m not working on a film I rarely socialize. But to be honest, drinking coffee feels like the only consistent activity in my life.

wildness

Would you say that you’re creatively satisfied?

YoonI’m satisfied with the creative works I get to do, but never creatively satisfied.

wildness

What are you working on at the moment?

YoonI’m trying to finish a novel and start a new screenplay.

wildness

Finally, what are you reading at the moment? Who would you recommend?

YoonAs usual, I’m reading several books at the same time. For example, Vilém Flusser’s Post-History and Michel Faber’s Undying. A while ago I read James Salter’s A Sport and A Pastime for the first time and was very impressed with his impressionistic prose. I would recommend it.

Read more from Issue No. 13 or share on Twitter.