An Interview with Tom Chivers

— feature

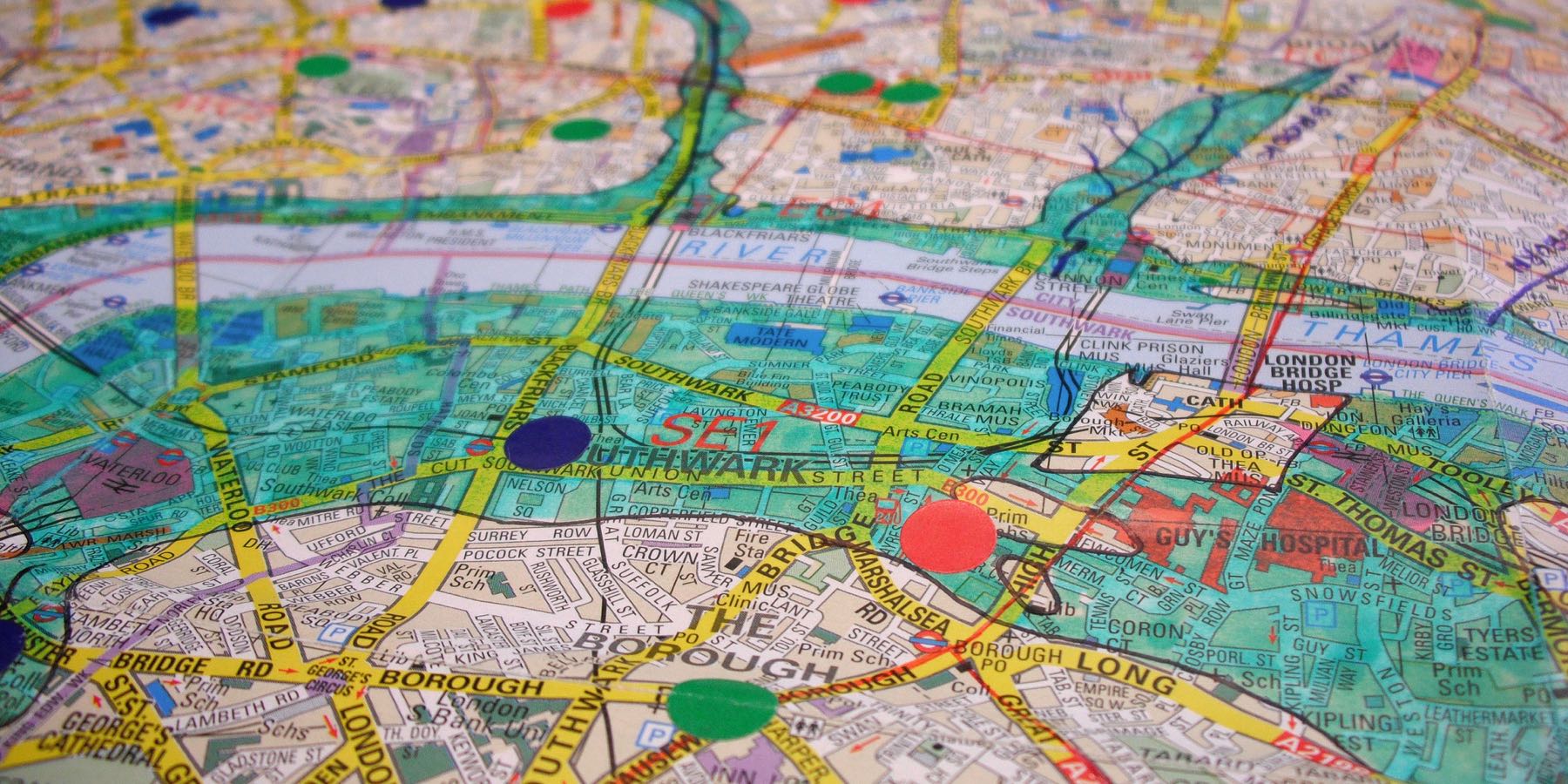

Tom Chivers was born in south London in 1983. His poetry publications include How to Build a City (Salt, 2009), The Terrors (Nine Arches, 2009), Flood Drain (Annexe, 2014) and, as editor, the award-winning anthology Adventures in Form (Penned in the Margins, 2012). His latest collection, Dark Islands, was published in a limited edition by Test Centre in 2015. Tom has made perambulatory, site-specific and audio work for organisations such as LIFT Festival, Cape Farewell, Humber Mouth Literature Festival and the Southbank Centre.

In 2011 his poem ‘The Event’ was turned into an animated film by Julia Pott and broadcast by Channel 4; it has subsequently been screened at film festivals worldwide and viewed over 100,000 times online. Tom is currently writing a non-fiction book entitled London Clay: Journeys into the Deep City. He lives in Rotherhithe and works as a publisher and arts producer.

How does your latest collection, Dark Islands, differ in tone to your previous collection, How to Build a City? How do you go about forming a new collection?

ChiversDark Islands is more precisely conceived than my first book. It’s a shot of ink-black espresso to How to Build a City’s frothy latte. The poems are literally shorter in most cases. And they gather around a tighter network of ideas. Death and money figure large. The city, of course. And islands. I’m also more sustained in my deployment of stylistic tricks—for instance, the collision of unlike images and voices.

What, perhaps, connects the two books is a propensity for satire. But, increasingly, the jokes come in all the wrong places. Dark Islands is much more apocalyptic than my first book, which is not to say it’s without redemption.

wildness

You mention the looming presence of death and money within Dark Islands, is this as a direct reaction to the state of the society we inhabit? In what ways do you feel your approach differs to that of your contemporaries?

ChiversNeither fear of death nor obsession with money are unique to today’s society, but perhaps it is true to say that most poetry has not, over the past twenty years or so, been interested in engaging with the form of modern paranoia that has emerged since the 1980s (when I was born) or since the advent of globalised high-tech markets, the internet, etc. A lot of the death and money in Dark Islands emerges from a way of thinking about London, too. It’s a city that has always attracted a certain ‘live fast, die young’ mentality, and that can make it thrilling but also a difficult place for many people to live.

My friend the poet Chris McCabe, who helped me edit the collection, has written an incredible book called Speculatrix, in which he looks at the state of the modern city through the gauze of Jacobean London, drawing parallels with phenomena like pay-day lending. I really admire the bravery of his writing, which always has a political edge. But I think for both of us these ideas are drawn from personal neuroses first. And these are things I have developed throughout my life, by living in the city, or I don’t know why. This might not come across to readers immediately—because I use a lot of techniques to hide myself in the poems, to disguise my voice—but Dark Islands is a really confessional book. I love giving readings, because it’s an opportunity for me to play with that tension.

wildness

Throughout your work, landscapes play a prominent role, how would you say location impacts you creatively, and subsequently, the work you produce? What is it about the city as a character that intrigues you?

ChiversThe Romantic notion of landscape suggests to me a kind of horizontality; a landscape is something you look at/across, or walk through. But what excites me about writing urban poetry is the idea that a city is a vertical space. London’s verticality is both literal (from underground rivers to thrusting skyscrapers) and historical (the idea of digging down through the skin of a place, through multiple layers of meaning).

I don’t want to write dead poetry of observation, but instead register something of the fluid psychological interactions between people and places, whether that’s bankers in Cornhill (‘Flush, cashed-up’), anti-capitalist protestors outside the Bank of England (‘in the costume of the dead that is to say / masked and painted’) or the ghosts of ancient Rome (‘emerging from the ground like the risen Christ’).

The city is such an alive place. There is a kind of constant electrical static running through it. As a kid I used to sit up late tuning in and out of police radio in south London. I hope reading my poems is a bit like that.

wildness

You also seem keenly aware of borders (be it through the imagery of the island, or the clash of traditionalism and modernity, of the past and the future); how important do you think it is to understand the ways in which life intersects at these points?

ChiversHumans think in borders; it’s our way of processing change. I lived in Aldgate for nine years—one of the historic entrances into the City of London. Of course the gate’s not there today. But there used to be a labyrinthine of pedestrian subways underneath the site, where a band of metal was set into the ground to represent the boundary between the City and Whitechapel. I’m fascinated by what’s happening to that area, and others, as a result of long-term urban planning. It’s a kind of test-site for what one might call ’hyper-gentrification’—the City, the UK’s financial hub, spreading east into the poorest borough in London. A whole, complex history of an area—a history of protest, migration, rebellion and creative energy—under threat of being erased. I don’t know a lot about duty, but as a writer I feel a great impulse to document that erasure, to question what is going on, what is lost, what is gained, and for whom.

Although London is my number one obsession, I have also written about other landscapes. At the end of 2013 I spent two days walking and mapping the River Hull from Kingston-upon-Hull to Beverley and back. The resulting poem, ‘Flood Drain’ (Annexe, 2014), is very much about those points of intersection between industrial and rural, between past and present, dry land and wet, and it attempts to create a dreamlike atmosphere in which borders become not barriers but ways in.

wildness

Your work has drawn tonal comparisons to both Dickens and Ballard; what impact does the work of other writers have on your own writing?

ChiversIt’s incredibly humbling to be compared to some of the great London writers of the past. Dickens and Ballard both wrote extensively about the underbelly of the city, and drew from lived experience to create extraordinary yet believable worlds. If Dickens were alive today I think he’d be shocked to discover how inequality in the city not only persists but grows, but I think he’d also be fascinated by the possibilities of new technology. I reckon Dickens would have been an early adopter of virtual reality, and definitely a Twitter star.

I recently walked from Hackney Wick to Westfield in Stratford past the Olympic Stadium. It’s interesting to imagine Ballard’s eye being drawn east towards this new post-industrial landscape of motorway flyovers, canalised rivers and giant shopping centres.

wildness

When creating your pieces, do the titles come to you organically or are they something you have to work on? Similarly to this, do you believe artwork should be an extension of the work within?

ChiversFor me, the title almost always comes after the poem has been written. I am drawn to monolithic yet mysterious titles like ‘The Event’ and ‘The Bells’, with the hope that they will draw readers in to a slightly off-kilter world.

I’m lucky to be with a publisher who makes beautiful, limited edition books that become collectors’ items. Their process is always sensitive to the content of each book, so for Dark Islands the entire book is printed in reverse—with the words in white against a black background. It creates an unusual, immersive reading experience, and one in which the poems resonate in new ways that are unexpected to me.

wildness

How important is being part of the greater creative community to you?

ChiversIn the last few years my work as a poet has begun to be recognised outside the poetry community, and for me this has been a great liberation. I really enjoy having conversations and collaborating with a wider group of artists and writers, especially around issues like landscape, wildness, ecology and the city. Although some of my techniques as a writer are non-conventional, I always intend for my work to speak to a wide audience. I have found that Twitter is a great way to share ideas and find writers and artists with mutual interests.

Can you tell us about what you’re working on at the moment? Do you tend to focus on one project at a time, or do you find yourself split between ideas?

ChiversI’m currently taking a break from poetry to work on a non-fiction book entitled London Clay: Journeys into the Deep City. It’s a book about the city beneath the city: a hidden landscape of lost rivers and secret woodlands, of marshes and islands long buried underneath the sprawling metropolis. The research is taking me down into the sewers and out to the post-industrial edgelands of London. It’s also an autobiographical book—it’s about growing up in a city that is constantly changing.

wildness

Are you creatively satisfied, or are there things you’d still like to work towards?

ChiversI doubt I will ever be creatively satisfied; a little thing called time tends to come in the way. I would like to make more audio walking work (in 2013 I developed two walks down London’s lost rivers, The Neckinger and Walbrook Pilgrimages, that audiences would experience on headphones). I also have a great idea for a historical novel, but that’s going to have to sit on the shelf for a few years at least!

wildness

Who or what are you reading at the moment?

ChiversI’ve just finished reading The Wake by Paul Kingsnorth (co-founder of the Dark Mountain Project). It’s written in a ’shadow tongue’ of Old English; in his hero, Buckmaster, Kingsnorth has invented an Anglo-Saxon Nigel Farage. It’s utterly gripping. I’m now ploughing through Paul Mason’s PostCapitalism, which is heavy on economic theory but remarkably compelling.

Read more from Issue No. 2 or share on Twitter.