An Interview with Michael Salu

— feature

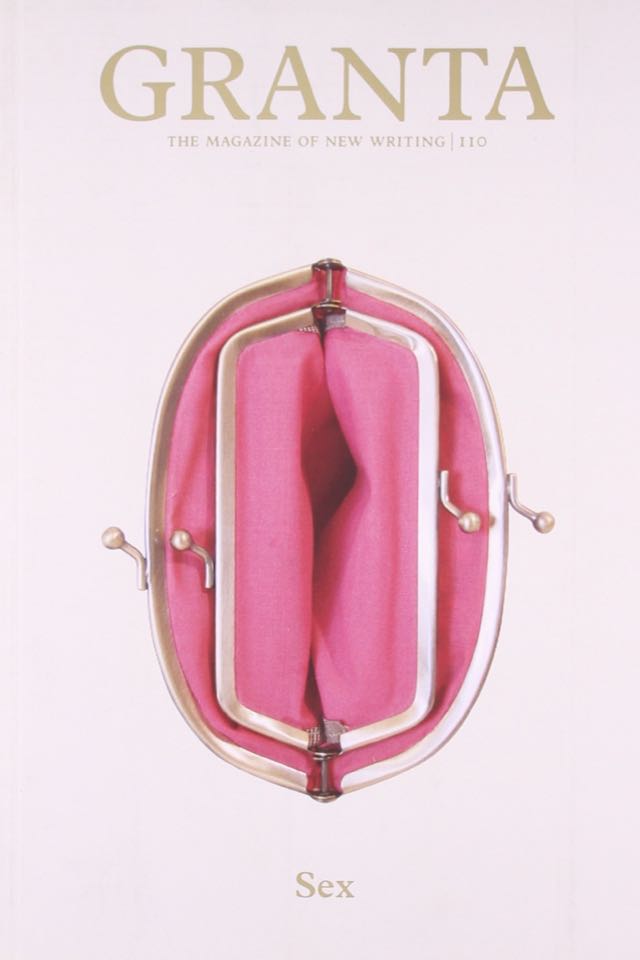

Michael Salu was formerly the creative director and art editor of Granta during which time he created numerous original features with art and photography, publishing and collaborating with a host of established and up and coming artists including Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, The Chapman Brothers and Yinka Shonibare. He created a distinct aesthetic for the publishing house across its magazine and book activities, collecting a number of awards along the way. Before Granta he art directed and designed a range of titles for the literary division of the Random House Group, producing designs for a number of classic and contemporary writers including Italo Calvino and Raymond Carver.

Salu now runs a multidisciplinary creative consultancy SALU which produces narrative driven creative work across platforms. He is also a co-founder of the cross-disciplinary art event series Local Transport and is currently finishing his first collection of stories and essays, whist working on a script for a feature film.

Could you talk a little bit about the path you’ve taken; were you always interested in the arts, or was there a specific moment that triggered this passion?

SaluI can’t quite see exactly when or how it happened, but I’ve always recalled a vivid capacity for imagery both immediate and implicit. Even now, I have lucid visual memories of my really early years, such as discovering an 80’s porn stash under my uncle’s bed aged seven, or writing little alternative stories to the Quentin Blake illustrations in Roald Dahl books. I also recall my Nigerian family’s interest in Bollywood movies during the 80s—maybe a precursor to the power of Nollywood today? Though I’m not certain whether it was ‘a thing’ in Lagos at the time.

I recall immersing myself in Conan the Barbarian comics and later Manga films. Again, at around the age of seven or eight I discovered public libraries, astounded one was able to take twelve books from the library at no particular cost as long as they were returned. This took me early into the bowels of literature, which very quickly became a personal, private space as opposed to an academic one.

wildness

Many people would know your work via the sparse, text-driven covers you created whilst working at Random House. The covers are a clear manifestation of what you describe as a desire to “convey an idea concisely, with as little fluff as possible”—how has your vision of art and imagery changed over the ensuing years?

SaluGood question. Yes, I’d say that my perspective has changed somewhat. I guess that was because narrative through clarity made the most sense to me as a core fundamental of a design language I had been honing for myself at the time. Now I suppose my thinking is different, there’s a merging of both critical and creative thought, meaning less reliance on form. That said, such design training and the capacity to execute imagery to a higher standard has allowed me to subtly create quite subversive subtexts and give shape to the smaller, less tangible spaces we find in digital and visual communication.

wildness

Between 2010–13 you worked as the Artistic Director for Granta (a role John Freeman and Ellah Allfrey birthed for you), was this a fulfilling period? And, as you are again working with John at Freeman’s, can we assume that relationship was a creatively rewarding one?

Salu

It was indeed, and the first time a professional position had really given an outlet to the myriad of things I did. I had entered the creative industry being dissuaded at the time from being interested in or from doing too many things, but that was always how I’d seen a creative practice to be, so I found that rigidity within the industry frustrating. My interest in art, photography, literature, film and design came together in that role. It was a position I needed to shape myself and became a hybrid role of sorts, both art director and art editor.

So on the one hand I was working closely with artists and photographers, looking to progress the photo stories within the pages of Granta and the broader discourse around the tradition of photojournalism, whilst also using images in an other way to look after the general appearance of the magazine and the publishing house as a whole. It sounds like this could have been a discordant responsibility, but I gradually began to shape the conversation we were having with imagery right the way through our activities. If there was a frustration, it was the lack of a strong digital infrastructure at the time to really help some of these holistic conceptual ideas get out there.

I think John had a similar approach as editor, less defined by publishing reputation and instead ensuring a magazine with such a legacy retained an urgency and could speak to the way we read today, as well as aim for new readers. We discovered our similarities pretty soon and began early in the timeline of an issue to work conceptually together. He and Ellah were the ones I would bounce ideas off and vice-versa—we didn’t always see eye to eye of course, and I would say maybe my taste (certainly visually) is probably more visceral, more transgressive, but overall I thought we made a dynamic team.

John and I have continued this with Freeman’s, except, compared to Granta, this journal is very much him and I’m tasked more with capturing what that smells like. I know him well, and we definitely have a creative understanding and a lot of personal parallels, so we spur each other on. I think there’s a similar desire to make sense of the world.

wildness

Related to this, your short story “The Nod” features in the inaugural issue of Freeman’s, how did this come about? And, was writing fiction always an area you sought to experiment with?

SaluI’ve actually been publishing pieces for a few years now, though I’d say it really got going during my time at Granta. As the magazine grew in visibility, I was offered more opportunities to talk about the work I was doing through panel discussions, broadcasting and writing. I would also write pieces for granta.com about the process and the thinking around the work we were doing. We’d put on events, such as a conversation around the ethics of photojournalism, or discussing “The Other” with Dinos Chapman for the launch of the Horror issue of Granta.

John and Ellah are first and foremost about writers and I think once they discovered I was decent at this, there was no end of encouragement. I gradually received more opportunities to speak from my point of view with essays and short stories for magazines like Under the Influence and Litro, which then led to anthologies and lit journals. Writing actually started at school and was personally very important to me, but as soon as I received encouragement from academia about my potential, I lost interest (or just ran away) and opted to study art instead. I was possibly a bit misguided at the time, but this could now be seen as a benefit. John and Ellah simply dropped me in at the deep end as they knew I’d be ok.

I would certainly say having “The Nod” published in Freeman’s has been my proudest moment as a writer. To see my work alongside luminaries I’ve grown up reading, such as Anne Carson or Murakami is a real validation that I’m good enough to write at this level and with my own voice. A story collection is now taking shape. I think the need to fend for oneself bred a real desire to make a living doing something I could enjoy. Life is short.

I’ve only written short works thus far, but there are some ideas brewing that may work in a longer form. Taiye Selasi said to me simply, “when you have to write it, it’ll happen”. We’ll see.

wildness

The story itself contains the introduction of S.O.U.L.; something you also touched upon in your TED talk on imagery and your recent “Dear Marilyn” story. Do you now see the exploration of the conflict between physical and virtual (memory and actions) as central to your personal work?

SaluThere is a prequel to “The Nod” and the other stories from the collection in a piece I published in Science and Fiction (Royal College of Art / Black Dog Publishing) entitled “20 FAQs for S.O.U.L. (Systemic Obfuscation of User Liberalism)”. This text takes the form of a series of frequently asked questions about S.O.U.L., a fictional organisation I created that helps us predetermine our dreams and desires but through our own actions and behaviour. A corporate self-governance of dreams. This piece forms the vertebrae of the collection and the other stories and artworks respond to individual questions within this first piece.

S.O.U.L. is a kind of digital psychogeography which serves as a mainframe for these works and the collection. I’ve been exploring the dissonance between the simplistic binaries of modern experience and the evolution of our collective digital consciousness, and it surprises me how little we talk about the Internet and artificial intelligence in that way. It has a sentient presence and growth which is informed and can only exist as a result of our own actions and behaviour and what we feed into it. A dormant world cannot feedback to itself, inform itself or evolve itself, and we often talk through ignorance about the way we live everyday as though it is just a necessary evil and don’t spend enough time trying to understand it. Maybe because our digital selves evolve more quickly than we do, so there isn’t time for ethical or moral discussions of how we’re using and developing technology. It’s a fascinating mirror to ourselves that we have created in such a short space of time and in some ways presents our ultimate honesty, our purest self. A self made apparent through collation and obfuscation.

I think we live in an incredible time, and S.O.U.L. is my own riff on all this, with maybe what you might call a meta-construct. It is a hypothetical virtual reality space (even though fiction itself is already a virtual space) through which I’m tackling a variety of experiential nodes on the evolutionary changes to human communication and experience (or lack there of) that technology affords us. Each individual story or text is conceptually linked to another and very semiotically driven, working I guess in the same way as browsing links, or grouping associative elements with tags.

wildness

In a previous talk you mentioned that music and sound were extremely important in informing you creatively; how much does your recent theatrical and cinematic work rely on the soundscapes created for them? And, do you enjoy the creative-merging of fields?

SaluWell coincidentally I’ve just completed a short film entitled Nocturnes, which is just about this private space and nothing else. It was an idea I’d been thinking about for a while, and when I was commissioned to produce a piece of artwork for Piano Day, saw it as a good opportunity. It is a portrait of a pianist (Adam Longman Parker) playing a Chopin piece. The camera focuses solely on the pianist’s face and does not move through the entirety of the piece, leaving you exposed to a very intimate and usually hidden space. It feels illicit, like one should not intrude and this, of course, is the point. Sound has always been that lubricant for me. It creates fluidity between thoughts, helping to give form to narrative and mood. I don’t think there is a day I don’t listen to music and find it in my work, from techno, right through to classical.

I’ve been considering collaborating with a musician to build a soundscape around this collection. With the film and performative works I’m developing, I’d say, I’m very influenced by the meditative tonality of Terrence Malick, Gus Van Sant, Andrei Tarkovsky, Alexander Sokurov and Nuri Bilge Ceylan, but also the more polemical and playful Godard, Buñuel, Fellini and Pasolini, and early video art, as well as various strains of photography.

wildness

Between Granta and Freeman’s, you have experienced a switch from a UK to US-centric journal; is location important to you? And, in what ways does it affect the work you produce?

SaluI moved a lot growing up and that installed a nomadic spirit within me, so I still don’t really have a desire to call anywhere home. Currently I’m in Berlin, but I don’t yet know where I will be next. I think this nomadism is reflected in my interests, my identity, the outsider position I take with cultures and politics, and the older I get the more of a bird’s-eye view I develop which leaves room to create interpretations of different spaces and discourses, like that which is happening in the journals I’ve worked on. Freeman’s, I think, is still as global in perspective as Granta, but given where John is from and the responsibility he now has, it is much more his own voice than that of a literary legacy. Which I think comes with more urgency, as we can often partition the community around literature from the real experiences and lives we might actually be writing about. I’ve always found that to be a bit disquieting.

Literature is generally marginalised when alongside other forms of ‘entertainment’, yet it serves as the creative repository for most of them. My recent story in Freeman’s talks about a white man experiencing (through Virtual Reality) the world through the eyes of a black man. I’m interested in representing identity beyond the constraints within which it currently exists. This in particular is why I deploy the hex colour chart for use when talking about race, a little sardonic poke at its surface level arbitrariness, but its equally rigid self-classification. The story also covers self-loathing but also camaraderie amongst black men. It covers interactions that happen primarily on the street, or at night, in clubs cloaked in fantasy. Yet the people I’m writing about will probably never read this piece—just a smaller pool of literature enthusiasts.

If anything this is what I’d like to step beyond, maybe find another way to publish short stories to reach that audience.

wildness

How important is being part of the greater creative community to you?

SaluOver my career I’ve accumulated a vast creative network of brilliant people all around me. This allows me to execute ideas in whatever form they need to take. I think ideas, conceptual thinking and original narrative perspectives are my strong point. I can then collaborate with others who’ll have complimentary skills to help execute a solution. Film is a good example of this for me and an area I’m reaching further into.

Though, on the other hand, creatively I’m a little hermetic. As in, I’m not so concerned with trends, particularly with visual projects we still take on through my studio. I mostly just think about the best way of executing an idea, or finding a creative solution. The aesthetic is then an automated byproduct of understanding the code within images.

wildness

What does a typical day look like for you? Do you have any particular practices or routines?

SaluI wish I did! I used to beat myself up about my lack of structure, but now I embrace it. Though, as writing has come to the fore, I’m trying to instil a bit of routine—I hear this is what writers do. I hear stories of waking at an ungodly hour to spend a few hours putting down some words. I’m not yet sure about this. I move with the current, sometimes I’m up working late because I’ve hit upon an idea and end up geeking out in a darkened room with a glowing screen, other times I rise early where my written work in particular tends to be more crisp. If I can add in a bit more routine, then maybe I can finish the story collection this year. One hopes.

wildness

Can you tell us about what you’re working on at the moment? It appears that you tend to focus on multiple projects at a time, do you find yourself split between these ideas?

SaluIt’s a very associative process, I rarely work on one thing for too long, when suddenly I’ve thought about something else tangentially related, then I make notes for a third thought, which in turn leads me back to point one but now at a 56 degree angle. At the moment I’m trying to focus on completing the bigger projects. It has become important to now focus more on my own work. Over the years I’ve given a lot of creative energy to others—collaborative projects and helping to tell other people’s stories—but increasingly I’m more interested in shaping my own voice.

Finishing this first story collection is high on the list and I am also embarking on a feature film project with directors Luke Seomore and Joseph Bull, for which I’m writing an original screenplay. It’s a story with a strong philosophical framework, within which there are many questions I’d like to pose about faith and hope, emancipation, and moral signifiers. It’s set in the South of the U.S., a modern, southern gothic odyssey. It is definitely time for me to consolidate my work.

wildness

Are you creatively satisfied, or are there things you’d still like to work towards?

SaluSo much. I’ve spent so many years creating and communicating with images and experiences, but words have become a much purer form of expression for me. I’ve barely scratched the surface with this and the potential is wild and exciting, but also quite intimidating. Film feels like the natural progression from all of the work I’ve done to date. I know how to create and produce imagery and I now have my own stories and theoretical spaces to explore. It does feel rather obvious, but then film is an industry with its own structural parameters that could also frustrate. I’ll keep trying to bend the rules as long as is possible.

wildness

How do you feel about creating something outside of yourself? What legacy, if any, do you want to leave?

SaluA very interesting question. I’ve been thinking about this a lot of late. What is it I’m driven by? A need to create or find meaning? Or a sated ego? Or achievement as colonial byproduct? As I go on I realise my early rejection of religion may contribute significantly to my propensity for analytical and somewhat theoretical thought today.

Recently I gave a talk at Falmouth School of Art, and trying to present the students with a selection of work that best represented my career trajectory proved difficult. It turned out to be quite a forensic examination. One of the students asked, given my distaste for today’s notion of the artist being face first, work second, did I see my more elliptical approach to a creative career as my art practice. It isn’t something I’ve ever said out loud, but that is exactly what it is.

Read more from Issue No. 3 or share on Twitter.