An Interview with Nikesh Shukla

— feature

For those who don’t know, could you talk a little bit about the path you’ve taken; were you always interested in writing, or was there a specific moment that triggered this passion?

ShuklaI’ve always been a reader, first and foremost. One of the few things we did as a family was go to the library. My parents were always working. But every Wednesday, without fail, we went to the library after school. And I read a lot. I went from a really small school to a really big school when I was 13 and I felt really lost in that big school and it made me quite shy and I invariably ended up hanging out with the other shy nerdy kids. And we used to tell stories, write scripts, terrible poetry, and so I started to navigate the space between reading stories and telling them. And I love it. I love storytelling, both as a reader and a writer.

wildness

Over the years you’ve worked in a number of mediums—novels, slam poetry, podcasts, screenwriting, even a short-lived period as a rapper—how do you attempt to balance the many aspects of your personal expression? Does one have to suffer for another to be fully realised?

ShuklaTo be honest, I only really write books and scripts now. I spent a lot of my 20s thinking I’d be a world famous musician who wrote short stories on the side to show off my intellectual side. But I was the worst kind of rapper, I was woefully average. You can be excellent or you can be terrible and still have a ‘thing,’ but to be average, that’s the worst thing for a rapper.

I feel most comfortable in novels and scripts. I think I just spent my 20s doing everything I could hoping one thing would stick but I quickly found, especially doing performance poetry that I liked the artform to watch but wasn’t interested in getting better at it to improve my own craft, so I stopped. And it got to a point in my late 20s where the only constant was the prose writing so I decided to take it seriously and not work on anything else for a bit.

wildness

Related to that, how do you prepare/write differently depending on the way your words are going to be experienced?

ShuklaI know how to differentiate between something that will be a novel and something that’ll be a script. But I think, instinctively as soon as the idea arrives, I know what form it’ll take. There’s one script I wish I’d written as a novel (the one about cancer) and one short story that made a better short film (Two Dosas) but apart from that, yeah, I guess, I think in visuals and conversations when working out plot beats anyway, and that tends to mean that there’s a lot of dialogue in my novels and a lot of subtext and meaningful symbolic stage directions in my scripts. I’ve learned that with the latter, no one cares. Tell me the story. A script is a recipe not a work of literature.

wildness

You’ve discussed before, and indeed your novel Meatspace is in direct reaction to this, that the ever-increasing investment in our virtual presences is detracting from our humanity. When discussing your mother’s death, you commented that her “digital footprint seemed more indelible than her soul”—this notion that we’re somehow losing ourselves is haunting, can you see a way out, a way to recapture our own fleshed-out self?

ShuklaI don’t know. I find, increasingly, in a world of news being delivered as it happens and hot takes for clicks overtaking thought-out comment, that we sometimes lack distance and hindsight to be able to take stock of things. If we’re constantly self-narrating, like on Instagram stories or Snapchat stories, then we’re documenting our lives as they happen rather than with any reflection. I want more reflection. Obviously, I don’t want to malign the way we tell stories now and how it’s different to how it used to be, but it is important we take stock of what is happening with a degree of distance.

wildness

Over the years you’ve talked about the lack of diversity within the publishing industry, and whilst there have been some strides towards inclusion, it’s clear a lot more is still required. What are your thoughts on the situation currently?

ShuklaThat currently there are exciting deals being done for writers of colour, and there are some interesting interests that are seeking to address the problems in a long-term meaningful way and not a tokenistic kneejerk way, and I hope to never have the diversity conversation ever again and in order to do that, I have to remain hopeful about the current things being done. But time will tell.

wildness

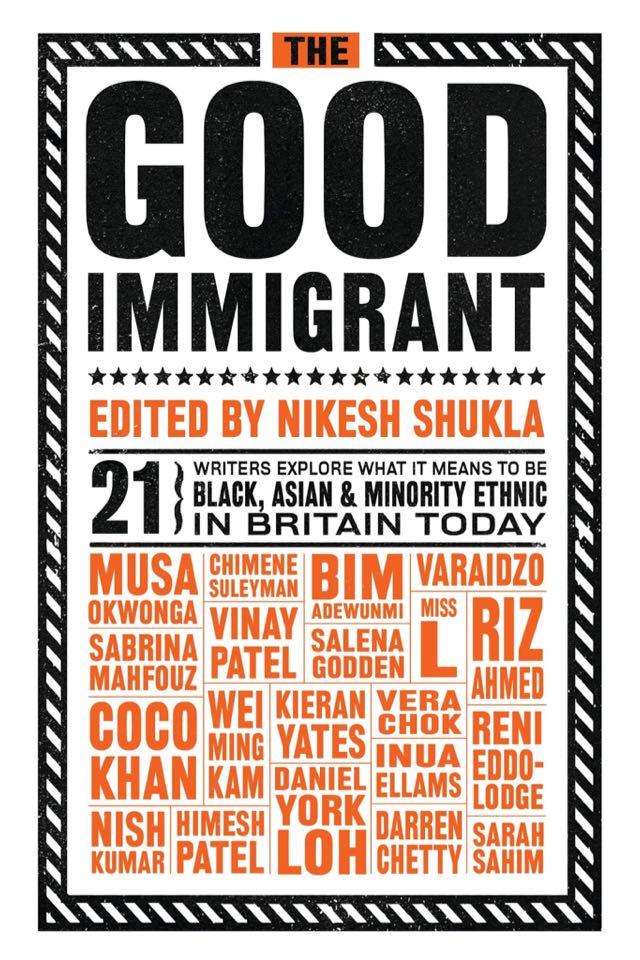

You decided to compile The Good Immigrant after noting the way the British immigrant population (as well as second and even third generations) were only being deemed ‘acceptable’ if they appeared to be required (doctor, lawyer) or had achieved something (athlete, entertainer). How has the reaction to the collection shaped your views on this? Has the fallout from Brexit cemented these beliefs?

No. I compiled The Good Immigrant as a proactive way of showcasing new writers of colour I was excited about, after having sat on too many diversity panels and witnessed a lot of bullshit around how nothing was changing. I thought about what I could do, and I know where the talent is and I knew someone at Unbound.

It was incredibly important that the book not be a political manifesto and the writers didn’t feel like they were being asked to be spokespeople for their entire race. It was important I got out of the way as much as possible. It just so happened all this was happening in tandem with the resurgence of the far right and the country wanting to regress to colonial times. I guess the book came out at the right time. Had it been more influenced by the time it would have been more of a political manifesto. I wanted it to be a classic piece of literature rather than a reactive piece about Brexit. But then, when we formulated it, Brexit was nine months away.

wildness

In several interviews you’ve noted the influence of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen; how do you feel the poetic form can compliment critical discussion on issues such as race and equality within the UK (and the US)?

ShuklaAs much as a novel or an essay or creative non-fiction or the novel can compliment critical discussion, I guess. I love Rankine’s poetic essays. I’d not really read that form before so reading her, I’d never read anything like it and it was utterly life-changing.

wildness

Could you tell us what a typical day looks like for you? Do you have any particular routines or practices?

ShuklaSure. I work at a place called Watershed in Bristol where I run a youth magazine called Rife. So I’m there five days a week, mentoring young people, editing the magazine, giving feedback, reading amazing work, watching incredible films. I write in the Pervasive Media Studio there most mornings till 9am, when I switch into work mode. In the evenings, I binge-watch Netflix then read then write then go to bed.

I’m pretty dull these days. I have a young kid. That’s my excuse. Having a young kid has bizarrely made me more productive though. It’s amazing how much time I wasted at the pub before I had a kid. Now, I have entire evenings to do stuff. And I don’t wake up in a fug most mornings, wanting to eat Hula Hoops in bed and feel sorry for myself.

wildness

How important to you is it to immerse yourself in the greater creative community? Linked to that, is location important to you? Does it affect the work you do?

ShuklaIt really is important. As I said, I work at a place called Watershed. And it’s an incredible space to be in. I’m around artists and creatives all day and it keeps the energy up. Also, most of my online interactions are with writers, either chatting shit about people on Whatsapp or chatting books on Twitter, and I really love that most of my daily interactions hold this spirit of creativity and collaboration and artistry.

wildness

Are you creatively satisfied, or are there things you’d still like to work towards? What legacy, if any, do you want to leave?

ShuklaI am creatively satisfied currently. Because the two books I’ve worked on in the last three years both have a publisher. It fluctuates. before either of them had one, I was frustrated they didn’t. And so on. It depends. There’s a lot I want to achieve going forward. I feel like I’ve done a lot of advocacy and campaign work for diversity in publishing, and while that has been important, for me the important thing is the writing, first and foremost. I’d also like a show commissioned on Netflix please.

wildness

Related to that, can you tell us anything about what you’re working on at the moment? Do you find that you’re constantly split between ideas?

ShuklaI’m about to hand in a hefty edit of my next novel to my publisher. And I’m writing this to you on the train to London to meet the editor of my first YA book, so she can tell me all the things wrong with it and what I need to do to make it A plus. On the train back, I’ll work on an edit of a script idea I have about two friends who solve crimes out of their food truck. So I’m always working on different things.

wildness

What are you reading at the moment?

ShuklaI am slowly reading Shashi Tharoor’s Inglorious Empire and quickly devouring Ghachar Ghochar by Vivek Shanbhag, translated by Srinath Perur. Both are excellent. I recently read and then quickly re-read Reni Eddo-Lodge’s forthcoming Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race. It is one of the most important books of the year.

Read more from Issue No. 8 or share on Twitter.