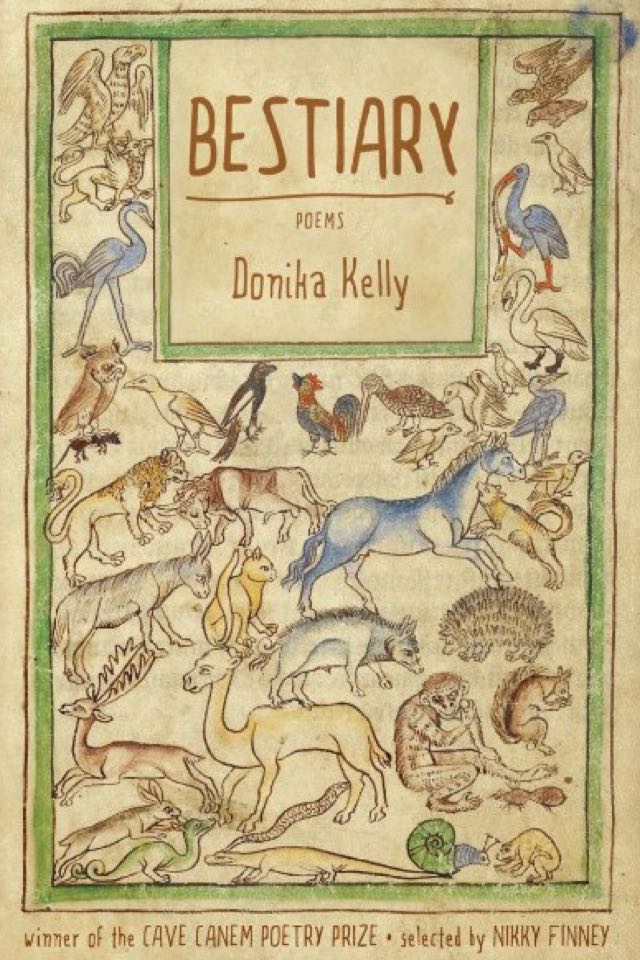

Bestiary

— Xandria Phillips

While a zoo is a colonial entrapment, a bestiary is mythology curated, is a catalog of the small vital creatures we cage at our interior. Home is where your dogs are. Home is where your gods are.

Donika Kelly writes, of a small space where the subject is outnumbered by animals. In Bestiary there is sense of the divine, the primal, and singularity’s role as the great equalizer among beings birthed and dreamed.

This singularity is most saturated in Kelly’s series of love poems, which invoke fantastical, queer creatures. The first in the series, ‘Love Poem: Chimera,’ sings in wonder at hybridity.

I thought myself lion and serpent. Thought

myself body enough for two, for we.

...

What strong neck, what bright eye. What menagerie

we are. What we’ve made ourselves.

Kelly positions the self as plural, while scripting agency onto creation. Imagine something terrifying and strange, and imagine how it chose to become what it is. The chimera resides at the intersections between human and animal, between myth and matter. It builds itself in reference to the wilderness in and outside of itself. The spiritual possibility begged: if the self is multiple and wild, what strange, wonderful, romance can self-love breed?

Some of Kelly’s beasts do not have names, or rather, they go by names that unmake them as beasts. These beasts are queerness, love, and anatomy.

[...] Love, I am made

for calling: bare breast, smooth tail,

the perfect balance of scales.

I have claimed this rock,

which is also your heart,

which is also the shell I hold

to my ear to hear what is right

in front of me. I am a witness

to the sea and the sun, to your body

lashed to the mast.

These beasts are longing, solitude and sleep.

This is spring of shambles.

Of meadows slow to flower,

of fire sooting the underbrush,

and, love, I am lonely as a bear.

These beasts are desire, voyeurism, and gender.

Call it comfort, or truth, how they look,

not at the camera, as women do,

but at one another.

Or to god.

How they know where their faces go.

They open their mouths. They spread

their cheeks. They come on everything.

On everything.

These beasts are father, memory, and preservation.

The louvered windows. The peach

walls. The buckling ceiling that needs

repair. The gusset of your panties

soaked with your father’s semen. Why

you no longer wear panties. Why he

deserves every arc of your boot. Why

the door is always locked.

Kelly’s rich, devastating, interior landscapes map the reader across a persona’s mutation through emotional stages. We are the pods of singularity, and these are the multitudes that may reside within us. Before reading Bestiary, the concept of memory as it exists housed in the body, always felt fossilized to me. Memory as a tenant in this menagerie is warm, and breathing, and pink on the inside. In Bestiary memory has legs, wings and fins, and cannot be drowned.