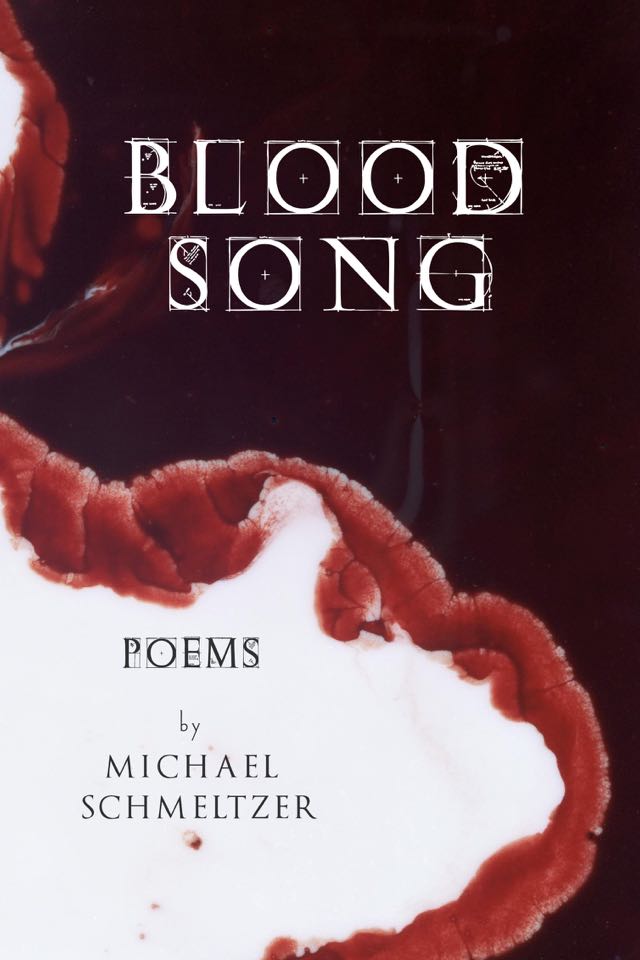

Blood Song

— Logan February

Often, with books, especially collections of poetry, titles are overshadowed by countless other elements. The design, the narrative, the poems themselves and their craft. But one way I know a book is truly special is if, days or weeks in its aftermath, I find myself pondering just how poignant the title is to the collection. A small detail, yes, but titles give the whole volume a larger clarity for me.

Michael Schmeltzer’s Blood Song is one of those volumes. A collection that does not shy away from the garish and the grotesque, but not from the soft music of yearning either. The poet, in this book, displays his skilful precision, balancing the world’s violence with its melodies. The speaker says it best himself in ‘The Memory of Glass’:

When I speak of the sacred

I conjure the exact scarlet

of a tanager

ruined by the windshield

of an oncoming car.

And while this tension, this contrast, is not uncommon in books of poetry, Blood Song has a distinct sound. Schmeltzer’s speaker elicits such familiarity and nostalgia that I, a Nigerian who has spent all my life within my country’s borders, get the sense that I know these parts of the speaker’s life. Yet, this book is evened out by the incorporation of a sense of wonder so vivid that I am left wondering where in the world this could exist. We, the readers, are not alone in this questioning, as the speaker tells us, seemingly in confidence: I’ve been here most of my life // and am no less lost.

Blood Song is a fluidly spinning top, hypnotic. At times, the wounds are ones we know all too well, perhaps even the childhood-specific / cruelties we inflict,

and at times they are strange and marvelous. In some moments, the speaker sings to us in ethereal voice, and then suddenly we recognize it as our mother’s song, our elegy, our love song. The mood of the collection flickers like a brave candle. I cannot help but trust the poet and his speaker to lead me on this journey. And what a journey it is.

In this volume, we witness our speaker grow from a child, into an adolescent / who mistook light // for safety,

into a man, a father who seeks to provide some semblance of this same safety for children of his own. He tells us:

When my daughter whimpers

in her sleep

I jolt awake. I am afraid

of the dreadful things she dreams

Here we see the preceding knowledge, the familiarity, the wisdom that comes with age. But in Isaac Newton’s Teeth, he confesses: I don't know enough / about the order of things / to say which came first.

This sense of losing track of time is integral to the work, and to Schmeltzer’s genius. In the reading of the poems, and in the poems themselves. My first reading of Blood Song was somewhat accidental. I only meant to flip through, because I, in fact, should have been studying for a test (I always say the benchmark for great poetry is its ability to distract you from terrible things). I read the opening sentence, Suppose we are not made of fire,

and was possessed by some bird of curiosity. The imagery, the speaker’s tale, the musical confusion—everything combined to make me get lost in time.

One poem in particular that calls out strikingly to me is ‘Portrait of My Father, Shirtless.’ In my mind, it explores the simultaneous communion and disconnect between parent and child, the one that is observable between the speaker and his parents, the one that he is forever attempting to calibrate with his daughters. In speaking of his father, the speaker says He did not bleed. We were not the same.

Again, blood as a prerequisite for familiarity, but not with a negative focus. The same tenderness that drives the book.

Michael Schmeltzer’s Blood Song is crafted with a gentleness that never fails to release an ache somewhere in me. In the closing lines of the poem, ‘Some Nights The Stars They Sour’, our speaker instructs:

Little bird, little god of flight,

land on the branches

of my splintered fingers. Do you remember

our inheritance, our names? I whisper them

as a reminder; hear and know. Here and now,

slit your feathered throat

so you pronounce us properly.

This seems to be a soft guide on singing the Blood Song. The questions of names and inheritance bring forward the same intimacy that is consistent in this brilliant book, convincing me that we all have our own songs of blood, and they are not so different from this.