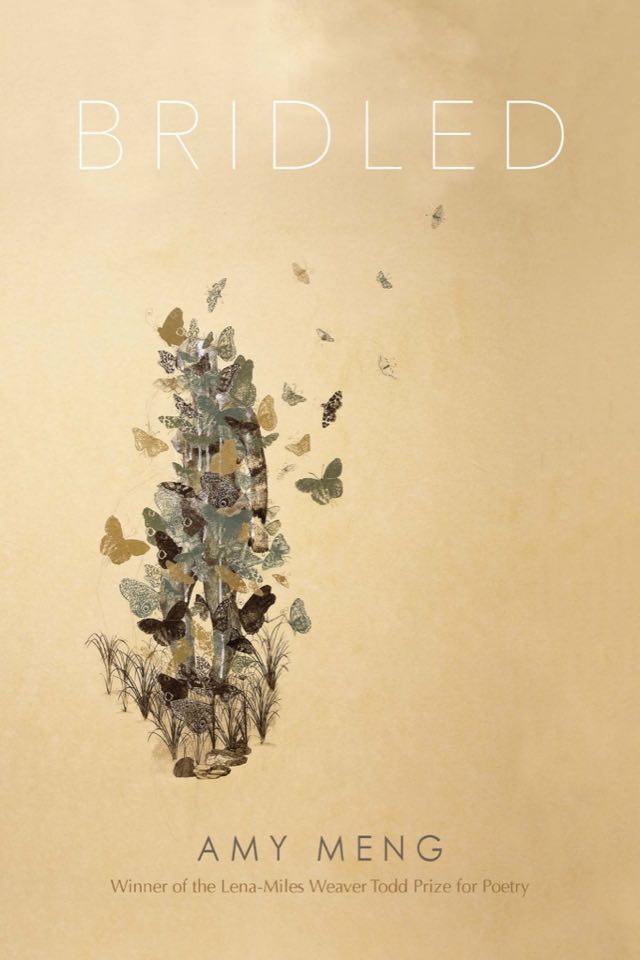

Bridled

— Ilana Masad

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “to bridle” means “[t]o curb, check, restrain, hold in.” That italicization is doing a lot of work there—it’s stressing the very nature of the frustration involved in this verb. To be bridled, as the title of Amy Meng’s prize-winning poetry collection, means to be “[f]urnished or equipped with a bridle, in various senses; curbed, restrained, controlled.” There is supreme control in this collection, indeed, yet it’s in the form, the language, and the tone, not in the personalities or emotions described.

The book as a whole deals with both a simple and an extremely vast subject: love. Not successful love, necessarily. Not love that’s present. Rather, it is love past; love curbed, restrained, or controlled; love held in; and, at certain shining points, the bright green shoots of a growing love of self.

In many poems there is a searing critique of the kind of things society teaches girls and women. In ‘If I exist the equation becomes more difficult’ the narrator awaits a lover whose work world is more important than she is. She recalls how fearless her youth was, but this changed into a seemingly dreary presence. Because I was a girl,

she says, I listened. I thought life / was the thing you got right: / clean as the camera’s flooding flash.

In another poem, ‘The first story,’ Meng ends with another truly breathtaking line: As a girl a specific myth // lodged in my ear and grew: / a woman finds her true self / only at the end of love.

There’s a hopeful note here as well—perhaps, at the end of this love, the narrator is managing to find herself.

The imagery Meng uses is often stunning in its intimacy and quietude, and certain images—a camera, a knot, ants, soldiers—recur. For instance, a short poem, ‘So it’s over, you said’ reads, in its entirety:

I studied you with a camera’s dead-on

closing shot

as you severed with singular effort:

a fisherman flinging back his weighted line.

A soldier’s brusque and violent mercy.

There is so much to unpack here, from the idea of dislocation and dissociation felt in moments of tension like a breakup, to the performativity of such moments, to the time-honored metaphor regarding plenty of fish in the sea, and all the way to the idea of love as an act of war, a campaign that ends with pretended mercy that is anything but.

Another subject tackled is that of beauty. In one of the three poems titled ‘After Maine,’ the narrator says: To leave he made me ugly: / after all, beauty is the leash.

And in “A Theory”, she writes of the change that comes over a person when they seem to become or grow up to be beautiful, and how despite the homes that open to beauty, the dinner tables set for it, she cannot forget when their long necks crisscrossed / above you like a canopy, keeping / their language from you.

But the narrator cannot forget, because, as she says, knowing holds.

Amy Meng’s Bridled is truly a gorgeous book, its intensity not flashy but quiet, both sincere and self-aware.