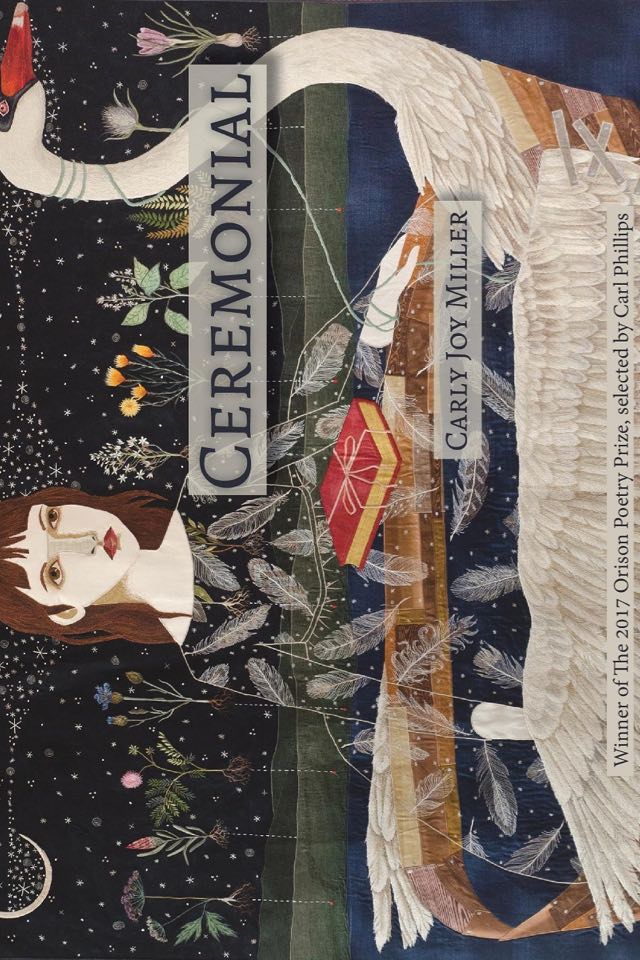

Ceremonial

— Logan February

Ceremonial is a frightful and thoroughly delightful collection of poems. Carly Joy Miller’s debut vibrates with restlessness, with aliveness, the churnings of the spirit. In this cruel and sacred landscape, the poet’s fluid narrative leaps towards and away from God and pain, music and longing—all with such agility that Ilya Kaminsky refers to her poetics as “the sensual art of speaking in tongues.”

Truly, Miller works everything up to a spirited dance, a disclosure of an otherworldly humanity. In Ceremonial, the body is a mere costume for the self, and the self is a beast of desire. Desire itself is at the core of the work. But despite the wildness of its wanting, Ceremonial remains light and airy with the most elegant lyricism, even at its most animalistic moments: “Nothing delights me more / than his horns. // How they rouge me.”

The world in this volume is bountiful with horned beasts; a fairytale in which the children don’t always make it out of the woods. The speaker, in her candid manner, tells us: “There are always killings in the quiet / line of trees.” This is the world that has formed our speaker and given her her grit, her bravado. In ‘Girl Gone Vile: Portrait,’ she asserts that it is “A kind of winning, to be the big bright bitch full of darkness.”

And full of darkness she is. In the collection’s first poem, the speaker confides: “My head / is a grief // prison.” And the reader is allowed to witness her coping mechanism, her search for music in every little thing. Miller brings melody to anxieties, to fears, to longings. It is this lyrical element that creates such a lush accessibility to the spirituality of the world in Ceremonial. In ‘Nightshift As Slaughter,’ she writes:

Dark laughter

behind me—these steps, these paws,

I know them all. Amen for fright,

the gaudy shriek. The gauze

of new hair over me, amen.

All of the shapeshifting in Ceremonial makes it an astounding artifact of human becoming. There is a sense of constant motion that makes the reader feel connected to Nature, and Miller’s not shy of making her emotions into living things. One poem vulnerably opens: “How ugly I’ve grown / into a forgetfulness.”

Ceremonial is a feast where human made beasts made spirits come to cavort. Everything is a verb—nothing stands still in this document of strangeness and healing. One can only surrender to the raw power of Miller’s music, as her speaker negotiates:

if you want to be saved

save yourself but if you want me

to sing I will sing.