Darker With the Lights On

— Alexandra d’Abbadie

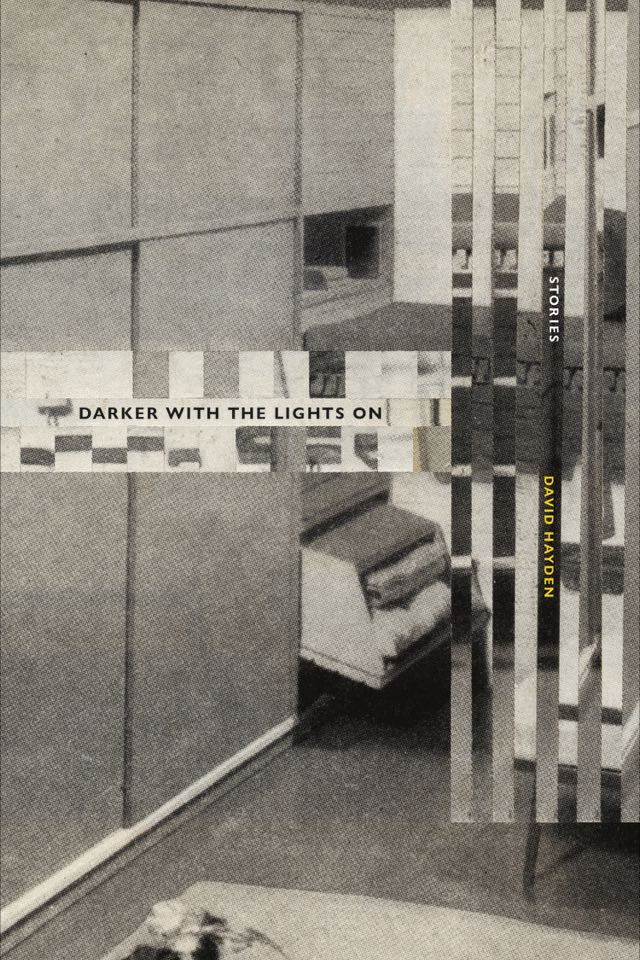

The English literary scene has an exciting new addition: Little Island Press, an independent publisher of fiction, poetry and essays founded in 2016. “Innovative, intellectually ambitious writing in elegant editions,” the website says of their books. I have David Hayden’s Darker With the Lights On in my hands, I concur.

The short story collection is startling, to say the least. One doesn’t quite know what to make of it. These stories are dreamscapes, absurdist nightmares; poised, elegant stories of male violence, memory; myths; brilliant manipulations of the written word that uncover and bring to the fore what it means to mourn, to grieve, to remember; the unconscious made image; mortality and the gradual perishing of the body; language, metaphor.

Summarising these stories is challenging—in fact, it cannot be done. You could qualify them with vague words that do not do them justice. Take ‘The Auctioneer’, for instance: it appears to be about the experience of memory, though one cannot be sure. A man who may or may not have killed his wife Ellen (she has disappeared, that we know) auctions his belongings. The auctioneer and the man form a bizarre friendship. The former delivers lines such as I believe that we haunt our own possessions. They’re dead, of course, but we are only slightly less so.

The man wants to be rid of such hauntings, yet clings to Ellen’s memory, or the act of memory. He can’t recall Ellen’s voice, but describes the “idea of a voice”: I realise that there were moments when I grasped what she was trying to say […] but none of this is available to me now.

He stares at the walls of his room, engaged in this act of remembrance for hours on end: I look into the nothing that hovers in the middle distance […] I scrub at it insistently with something abrasive, submerged—not quite thought. A dozen kinds of nothing peel off one another before I am looking at Ellen again.

The auctioneer encourages him to keep one of Ellen’s ball gowns, in order to ‘facilitate one’s memory’. The physical manifestation of the dress is too much for the narrator: Ellen appears in all her haunting, petrifying glory.

Plot obviously isn’t the point here. There are a few metatextual references to this, such as when the auctioneer tells the man the story of Paron. When the narrator asks what has happened to him, he replies Nothing…He died…He didn’t die…I don’t care. It’s just a story.

Hayden’s modernist stories set their own interpretative rules, and so the reader goes back, rereading—perpetually rereading. The author’s sentences demand it. It is no chore: Hayden has a remarkable gift for description. His precise, exacting prose absorbs you utterly into each story’s uncanny setting. His stories are disturbing, their affect is excruciating at times. It is an assuredly brilliant début.