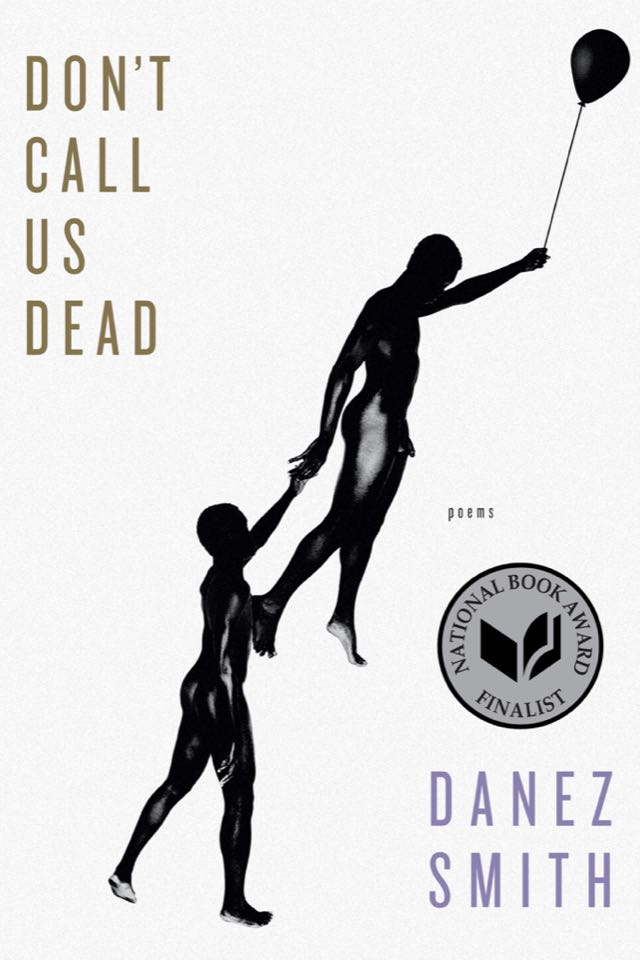

Don’t Call Us Dead

— Ilana Masad

When Danez Smith’s Don’t Call Us Dead first came out in 2017, I knew everyone was raving about it, but I wasn’t really reading poetry yet. A little over a year later, finally fully committed to bringing more poetry into my life, I picked it up out of a pile of books a friend gifted me. Once I picked it up, I couldn’t put it back down.

Don’t Call Us Dead opens with a long, multi-part poem called ‘summer, somewhere.’ It begins:

somewhere, a sun. below, boys brown

as rye play the dozens & ball, jump

in the air & stay there.

It’s an idyllic opening, boys like balloons, weightless in the summer sun. But these aren’t just paragons of romanticized boyhood—they are the dead, the brown and black boys shot by police in particular and white violence more generally. The boys in this realm of undeadness live freely, where “everything / is sanctuary & nothing is a gun,” where boys can be boys—not in the destructive way that phrase tends to be used, but tenderly. It is a world where boys can flourish, can rename themselves, can love their bodies and blackness and each other. In other words, it is a heartbreaking poem, so far from the reality we live in.

The second poem in the collection, ‘dear white america,’ is equally powerful and just as overtly political, but here the searing rage fairly jumps off the page as the narrator abandons Earth altogether, unable to stomach white supremacy and its attendant brutality for one moment longer. I read the poem right around the time I was rewatching Childish Gambino’s ‘This is America’ with the writing classes I teach, and I was struck not by the similarity in form or content—other than the title, the pieces are incredibly different—but by the way both pieces of art have an underlying exhaustion to them, a bone-deep tiredness that sits side by side with rage. ‘dear white america’ is a full page of block text, the sentences urgent as they unspool, but by the end, I sensed the desire to simply be done with this place, with this fight that so often seems unwinnable:

i’ve left Earth to find a place where my kin can be sage, where black people ain’t but people the same color as the good, wet earth, until that means something, until then i bid you well, i bid you war, i bid you our lives to gamble with no more.

The poems throughout the book are political, relating to identities Smith holds, not only as black, but as queer and HIV-positive. But identity, of course, doesn’t make for good art all on its own—Smith is a master of their craft. They convey emotion through the poems’ structures as well as through their content. In ‘litany with blood all over,’ the text jumps around the page, lines clearly demarcated, until the end, when the words “my blood” and “his blood” begin to alternate. The bottom of the page is then covered with those words, typed everywhere, on top of one another sometimes, as if Smith sat down at a typewriter and kept moving the page around randomly. It’s a striking effect, and one that gave me chills.

It is when I get chills that I know a poem is working for me, and on the incredibly hot and humid day and a half I spent mesmerized by these poems, I found my skin almost constantly goosebumped.