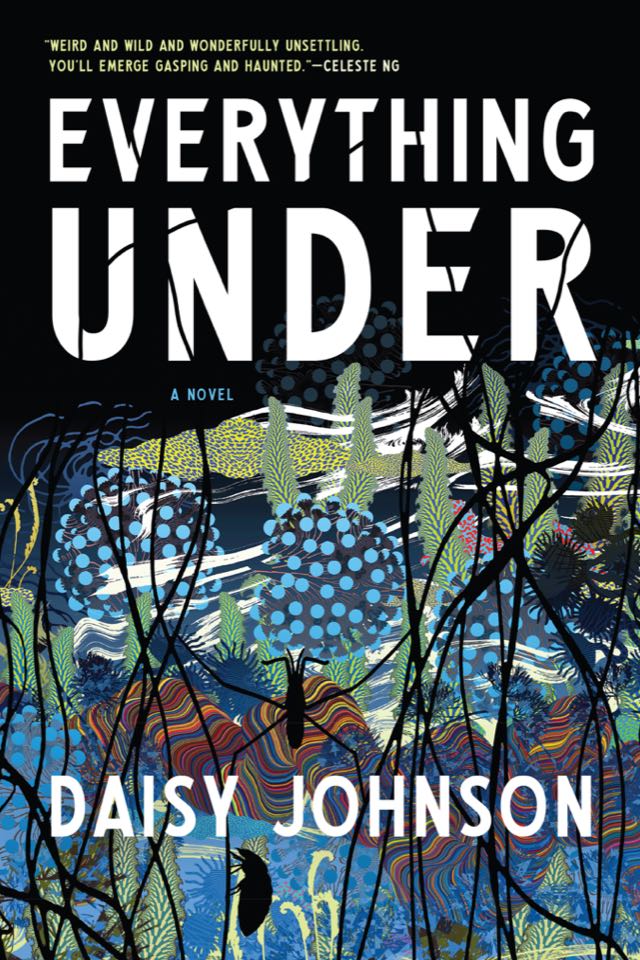

Everything Under

— Ariel Saramandi

There are novels that you don’t want to read in one sitting; ones which contain sentences so beautiful that you savour them, whisper them, before moving on.

The places we are born come back. They disguise themselves as migraines, stomach aches, insomnia. They are the way we sometimes wake falling, fumbling for the bedside lamp, certain everything we’ve built has gone in the night. We become strangers to the places we are born. They would not recognise us but we will always recognise them. They are marrow to us; they are bred into us. If we were turned inside out there would be maps cut into the wrong side of our skin. Just so we could find our way back. Except, cut wrong side into my skin are not canals and train tracks and a boat, but always: you.

A feast of language. It’s almost a torment—all to Daisy Johnson’s credit, of course—that Everything Under whisks you through the book by virtue of its stunning, clawing plot. You cannot put it down.

The novel is a rewriting of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex; it is narrated by Gretel, a lexicographer who has found her mother, Sarah, after over two decades of separation. Gretel attempts to piece together Sarah’s life, pieces that disappear in the brain fog of her mother’s dementia. Psychological trauma erupts in the mother-daughter’s recollections in the form of the Bonak, a river creature conjured from the eerie, isolated Oxfordshire waters.

Anyone who’s ever lived on or near an English river will appreciate how meticulous Johnson captures its essence: the smell of garlic shoots, the churning, weed-matted brown force that sweeps you away and pins you down. How on the river everything’s sinking, the half-bodied shape of the locks beneath the scum, the intestines of roots and trees. And I know that further upstream it grows narrow as a corkscrew; that there is a yellowing of foam along the banks and a heron stands in the chug of weir as if he’s waiting for something.

Such a place forges its own language, and with a language a world with its own laws and way of life; a world shared just between mother and daughter—and later, by a spectral person by the name of Marcus. Johnson’s clever working of the English language is marvellous: she creates visceral affect by deftly playing with syntax.

One wondrous thing that’s emerged from a year of unrelenting viciousness is the publication of such incredibly powerful books. Johnson’s novel is a howl of female violence and rage: the suffering of motherhood, of women and their fraught relationships with their bodies, of the many kinds of harm brought upon us for simply existing.