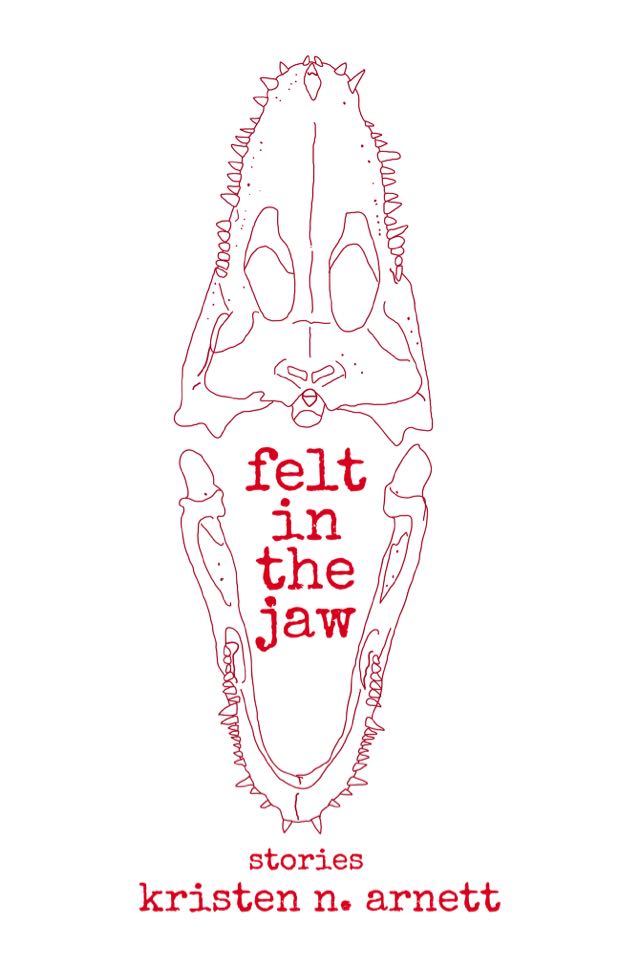

Felt in the Jaw

— Yael van der Wouden

One of my favourite stories from this collection, titled ‘Lebkuchen,’ starts like this: there’s a woman called Anja Dieter whose skin [glowed] like a fluorescent light blub and hands that felt like crumbled tissue paper.

Anja lives in a hot-summer suburban neighbourhood and is seen, for as far as the reader is concerned, only through the eyes of one of her neighbours, Nina Braithwaite. Nina either likes or dislikes or is simply taken by Anja’s very odd existence—which one of the three it’s not clear at first. All we know is: to Nina, Anja is a strange but unfocused notion of a person. A story more than a neighbour, a woman who, the people say, never laugh[ed] or smil[ed],

who never took visitors and […] never went on trips; no one had ever seen her operate a car.

Whose deceased mother, rumour had it, had been a practicing Wiccan.

Then Anja accidentally walks in on Nina and her neighbour, Bonnie Smithwick, mid-tryst, and everything changes. From this point on, the story reads as though the previously distant narrator is tumbling into Nina Braithwaite’s body. And by that I mean: from the moment Anja walks in on Nina and her lover, the narrative voice takes a sharp dive from the collective, removed voice of the neighbourhood, into Nina’s most interior life. We are thrown into her insecurities, the way she feels her body as she finds herself being seen by Anja Dieter ([feeling] all her imperfections as if they were lit up by neon signs: the slight sag in her left breast, the shiny white scar across her torso from her C-section

). Anja, in turn, fails to recognise Nina’s existence—bodily or not—altogether. She continues on her strange surrealist ways, walking in and out of rooms, boiling chicken, answering questions curtly. She registers nothing much, let alone Nina’s secret affair, and this seems to burn something within Nina—a desire, a need for recognition.

And in tune with the rest of this beautifully strange dream of a story, what follows is the escalation of Nina’s obsession with Anja. More specifically: her sudden obsession with the bodily presence of Anja (her doughiness,

her cadaverousness

), and how that body of Anja might collide with her own. Without spoiling too much of the ending, the story culminates in a gorgeous passage on what it’s like to want to consume another person, and what that entails, that need be fulfilled by that which we consume. To then not find what we need in the physicality of another. The story is titled ‘Lebkuchen,’ after the German treat, after—and this might be an overly excited guess on my part—the folk belief that the leb

in lebkuchen

stands for leib

: body. Kuchen, of course, is the cake, and together they make what Anja becomes: a bodily loaf, a thing to consume, to become.

And in one way or another, each of Arnett’s stories follows this theme of the confused and the bodily to a different conclusion, each unnerving and thrilling and queer in their own way. One of the stories follows the feverish fallout of a mother bitten by a spider in the night. Another peeks into the life of a woman who secretly nurses a mysterious bulging in her abdomen. One describes with fantastic accuracy the inexplicable and sometimes violent trials children put each other to, and another takes the reader into a world where the main character’s world of language begins to fall apart, stops to make sense.

When I first started reading this collection, I had it by my bedside and had decided to read a story each night before sleeping. This I managed for about two nights, and then concluded there was no way I could sleep after falling into these little worlds of curious haptic truths that Arnett paints. The writing is crisp and can seamlessly blur vaguely relatable personal notions—like what skin or pain or a headache feels like—to clear and universal narratives such as love, and death, and loss. It’s unlike anything I’ve read this year, and it surprised and thrilled me to no end. I have never been quite so aware of my hands while reading, while holding a book, or of how all my little phantom pains that seem oddly tied to the spiking aches of the characters whose lives I get to step into.

Best read: with a glass of cold water, in private, in public, on a bench on a clear afternoon, while wide awake.