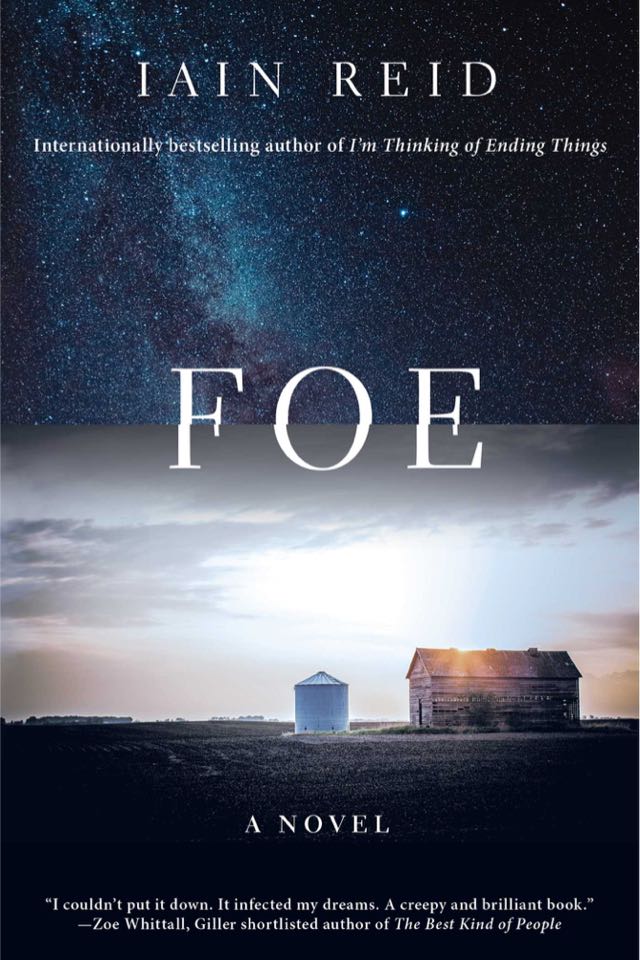

Foe

— Ilana Masad

Back in 2016, Iain Reid’s first novel, I’m Thinking of Ending Things, came out. An eerie meditation on loneliness, violence, memory, and more, it’s a quietly troubling book, its mood still spilling into me when I recall it. Now, Reid is back with another harrowing, strange story in Foe.

The novel opens with a pair of headlights shining through a window. Our narrator, Junior, is a man of few words, married to Henrietta, whom he calls Hen. Junior has a steady job at a feed mill—who the feed is for is never made clear—and Hen works too, somewhere, though the particulars remain mysterious. They live together in an old farmhouse out in the middle of nowhere, the landscape around them covered largely in canola, the tall weedy plants sprouting yellow flowers; it’s from their pods that the seeds that make the oil of the same name are harvested. Imagine it: endless fields of tall yellow flowers under a bright blue sky.

But all is not well. The headlights that signal the opening of the novel bring with them a man named Terrance who works for OuterMore, a company intent on sending humans into outer space. Junior is told that he’s on the longlist of folks meant to go up in the first wave of an experiment, though he’s never signed up for this or been particularly interested in such an endeavor. Terrance says that doesn’t matter, though: “I admit that you didn’t volunteer for this,” he tells Junior. “Not exactly. But you have talked about space before. Our algorithm picked it up.”

Over the course of the novel, we slowly begin to understand what kind of world we’re in. It’s the future, apparently, with self-driving cars, ubiquitous screened devices, and no one pretending that those screens don’t listen to us anymore. But unlike many a futuristic novel, Foe doesn’t try to tell us that this future is good or bad, safe or unsafe, progress or collapse. Instead, the novel’s focus is extremely narrow, homing in on Junior and Hen, and Terrance, when he’s around.

Terrance leaves pretty soon during his first visit, but returns two years later to tell Junior that he’s now on the shortlist—then he returns again, much sooner, to tell him that he’s been chosen to leave. But he shouldn’t worry about Hen, Terrance tells Junior, because OuterMore will replace him with a replica of some kind, an identical Junior who will keep Hen company while he’s away in space. Cue further eeriness.

As with Reid’s previous novel, the plot here—the actual storyline—is far less important than the mood and discomfort it conveys and the glaring question marks it brings up. The relationship between Junior and Hen is uneasy. Junior often tells Hen what’s good for her, insisting, for instance, that she play the piano in the basement more often. He believes what he’s saying, isn’t even aware of the way he’s assuming an understanding of her. This is something that happens in a long, isolated marriage, Reid seems to suggest—you begin to think you know a person who may, all along, be changing right under your nose. And it isn’t that Junior doesn’t listen to Hen when she tells him something is wrong—he does, he tries to listen, and he tries to understand. But he’s more caught up in the feeling of being chosen, chosen for this mission by OuterMore, even though he never asked to be. He’s swept up in the specialness of it:

What constitutes normalcy? I think if you asked fifty people, you’d get fifty different answers. There would, undoubtedly, be some congruities. But who decides what’s normal? Where does the line of regularity fall? […] I’ve always felt it about myself, going back as far as the memory of when I first met Hen, that day on the road, even then—a profound burden of mediocrity. But I’m sensing a change. I’m here after all! Right now! I’m having experiences, feeling desires, making decisions, building relationships, creating new memories. And I’m aware of them all happening at once. How can any of this be standard and typical?

In this little monologue, and throughout the novel, Reid seems to be interrogating a whole host of questions: what does it mean to be unique? How do power dynamics enter relationships, and how does the addition of a third party, a visitor, change those? How does unexpected, forced change affect us? Beyond these, Reid also seems to be asking, as a writer: how much world building is enough to convey a mood? How little specificity is it possible to give a character while still making them vivid? Reid’s spare writing somehow manages to convey urgency, discomfort, an uncanniness, while leaving large swaths of the character’s personalities and the setting to readers’ imagination. But he gives us enough, just enough, to keep us hungry up to the marvelous turn of an ending.