Fourth Walk

— Terry Abrahams

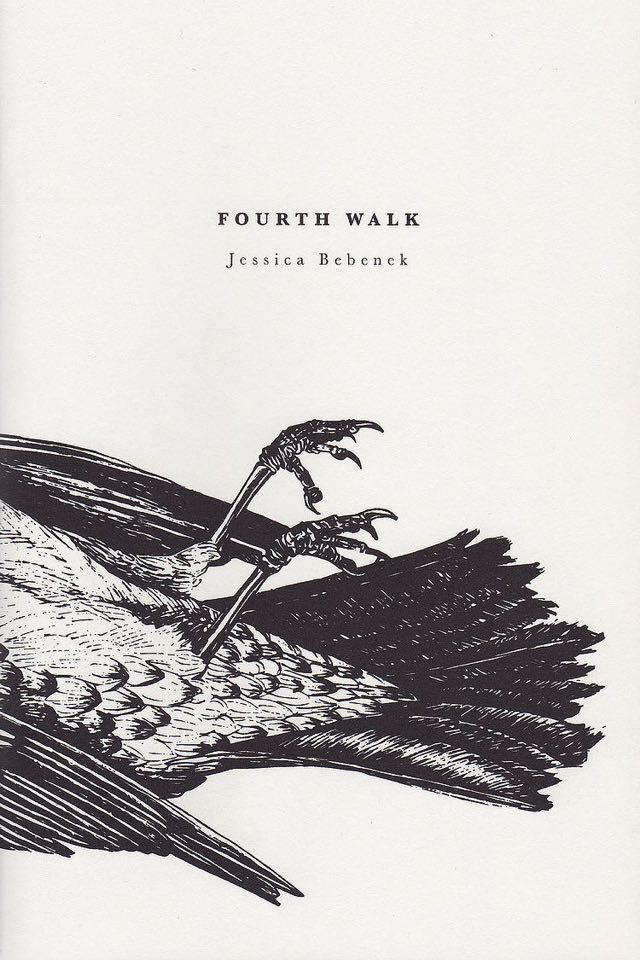

It’s not unusual, of course, for the eye to wander. I was drawn to the cover of Fourth Walk before anything else, having seen it several times in images online before finally holding it in my hands. The headless body of what can only be understood as a dead bird is in stark black ink on the already sparse cover. The written image of the bird itself appears—alive, and, to Bebenek, meaningless—in the poem ‘This is the Morning of a Meaningless Sparrow at the Window.’ Here, readers are not introduced to a sparrow as such, but rather to the narrator’s grandfather as he lies weakening, unrecognizable (and yet intensely familiar) to her. Fourth Walk is about, ultimately, the death of a loved one—and a look at the home grief makes for itself in Bebenek’s narrator, in her friends and family members, in her own home, even in her city.

Bebenek deals with grief in the way that many do: slowly, and sometimes not at all. The attention to detail matched with emotional response and expression found in these poems can sometimes feel jarring; other times, natural. Bebenek’s neat line breaks and pacing, coupled with her careful choice of words, create narrative poems that read with confidence. No abstractions here, though metaphors are utilized, and emotional response is generous. Narrative poetry can contain its own world or be a part of a larger whole, and Bebenek has achieved a neat balance of both in Fourth Walk.

Maybe I’ve just been listening to too much Fiona Apple, but Bebenek’s poetry brings to her music to mind. Like an exorcism of emotion, the poems within—like ‘In Waking’ and ‘On Melancholia’—express expression, meaning, to me, they are efforts in understanding one’s own feelings. As simple as it may seem, such a task is difficult.

What brings the collection together is the poem ‘Hospice.’ The last stanza reads:

I lied. There was a fourth walk, but it confused itself

with heart beat, the brain instructing the lungs to pump

within a vacuum. The feet finding sheets of stone beneath

themselves and these stones leading

around the side of the house, through several doors,

an accommodating hallway,

back into the room of the poem’s origin.

It was a room containing all the bodies I knew

in varying states of decomposition.

And so the poem ends. Bebenek’s beautiful control over the narrative leaves readers without wanting more or needing less—again, a balance is achieved that makes reading easy and enjoyable without being mundane.

The chapbook’s final poem, ‘Secondhand Elegy’, ends with the lines:

When we touch now in public

it’s polite, with a lightness

tinged by our letting go.

Whether hopeful or desolate, lost or at peace, the narrator has, in part, moved on from both the physicality and the emotional strain of her situation. To grieve is to eventually accept grief’s presence. Although it may never fully leave one alone, acknowledging it is there is one of the many steps in being able to accept it. Bebenek’s poems are an exercise of this, in my reading, anyway—here is an attempt to make grief palpable. I can hold this sadness, and flip through its pages, and once I’ve had my fill, put it back on its shelf and let it rest.