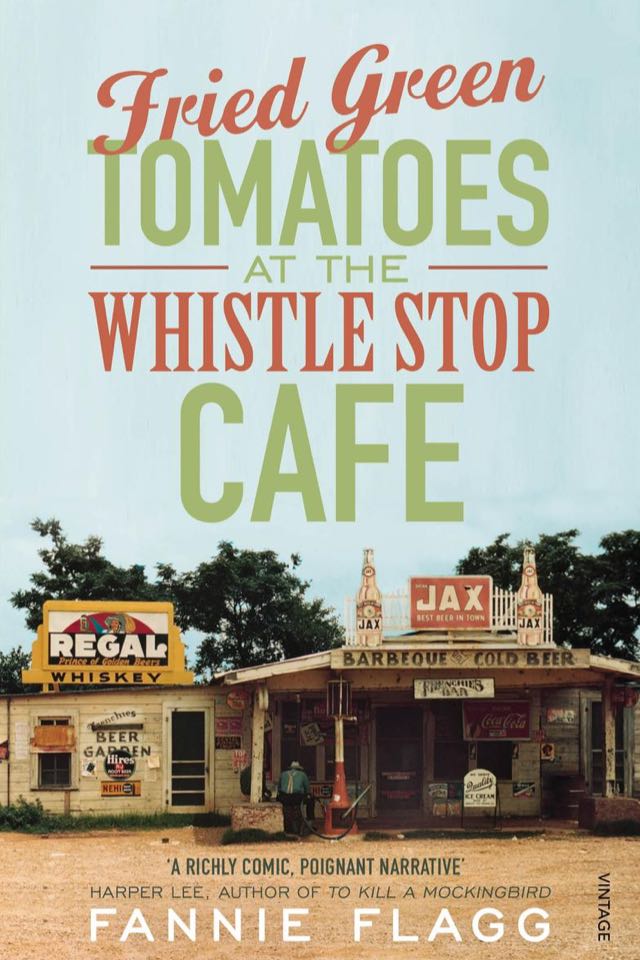

Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe

— Ilana Masad

Recently, with a surprising bit of free time on my hands, I finally turned to a queer classic that was recommended to me by a dear friend. She’d told me that I would love the book, and gave me her copy, inscribed with a beautiful note. It took so long before I could read it, though, that by the time I did I’d forgotten all about the queer element and got to experience the surprise and delight that comes with discovering queer undertones for oneself.

Fried Green Tomatoes is about Whistle Stop, a small town in Alabama, the kind of place where everyone knows everyone and is in everybody else’s business. The plot moves back and forth in time, focusing in on a few intertwined families: the white Threadgoodes, and specifically daughter Idgie and married-into-the-family Ninny; Big George and Onzell, an African American married couple who work in different capacities for the family, and Big George’s mother, Sipsey; and, along the sidelines, Dot Weems, who comments on the goings on in her town newsletter. These characters mainly appear in the part of the plot set in the past, except for Ninny, who is in a nursing home in the 1980s where she meets Evalyn Couch, a woman who becomes her friend and to whom Ninny tells large portions of Whistle Stop’s history.

There’s a lot about the novel that’s highly problematic in contemporary terms, but that means well, and it’s best to read the book as a product of its time and as progressive for the Alabama that is being both admired and critiqued in its pages. For instance, there are some scenes involving the Ku Klux Klan, which attempt to differentiate between white men who joined up to dance around in sheets and be silly and the white men who participated in the KKK’s hateful and violent activities. Ninny, who narrates, makes a lot of statements about how African Americans are just like white people, but sets up whiteness as the standard against which they should be measured (guess what—it isn’t). However, Flagg tries to balance out what appears to be simply the ignorance of this woman with scenes focusing on Big George and Onzell’s two boys, one of whom finds a great deal of joy in Birmingham’s largely black neighborhoods of the 1950s a 1960s, while the other experiences deep confusion when he is ignored by his niece when she sees him for the first time in years, because she’s passing for white in a department store.

Race isn’t the only subject that holds center stage in the novel. The other is, as I mentioned earlier, queerness. Idgie Threadgoode is coded queer from early in the book, when she decides that she will never again wear a dress. She is so stubborn that despite familial wishes that she wear a dress for her older sister’s wedding, at least, her mother ends up asking the tailor to make Idgie a bright green suit. When a young woman named Ruth, a few years Idgie’s senior, comes to hang out with her one summer, Idgie is smitten. The word “crush” is even used by Idgie’s mother to describe what she’s going through. When Ruth leaves, Idgie is heartbroken, and seeks comfort in the arms of a renowned “loose” woman, a free-spirited drinker, smoker, gambler, and all around awesome character named Eva Bates. The book heavily suggests that they get it on. Later, Idgie rescues Ruth from her abusive husband, and the two of them set up house and shop together, opening the titular Whistle Stop Café and living as a de facto married couple, raising Ruth’s son together.

Whistle Stop is, in other words, a highly accepting town. Despite Jim Crow laws that are still in effect early in the plot’s timeline, the Whistle Stop Café serves African American customers, and for cheaper prices too. Despite a general homophobia and Judeo-Christian attitude that would have reigned at the time, Idgie and Ruth’s partnership is accepted without question. The language isn’t as progressive as one would like, but again, this book was first published in 1987 and deals with characters who lived before the Civil Rights Movement took the country by storm, before gay rights activists were able to march through the streets without fear of arrest.

Words are certainly always important, and I will never say otherwise. But in Whistle Stop, actions speak louder than words. If only every person who spoke with old-fashioned terminology and problematic wording was, at the same time, acting daily in favor of true equality, we would be living in a very different world.