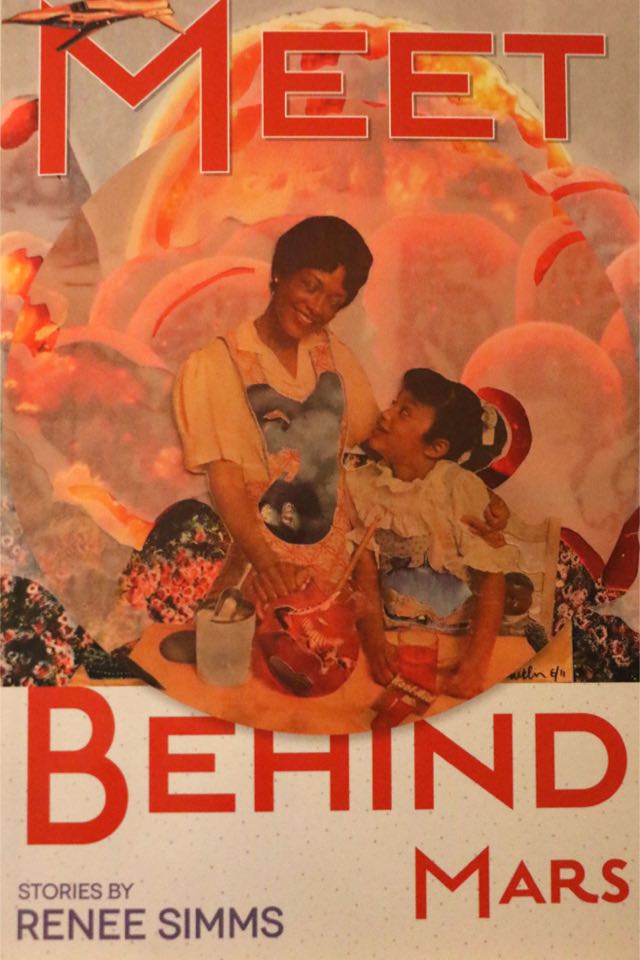

Meet Behind Mars

— Ariel Saramandi

In each of Meet Behind Mars’ incredibly tender stories, Renee Simms unfurls the way in which her black female protagonists navigate space. Not the cosmos, of course: the meaning of the phrase is explicitly described in the story that bears the collection’s name. Gloria Clark hilariously and poignantly describes the trials and tribulations of her son at school; as one of the few black children, Jesse’s body is constantly surveyed, punished, and subject to overwhelming racism. Gloria writes a letter to Dr. Lutz, the school therapist:

I recall what my sister said when I told her that I was moving to Durant, Washington. ‘Why are you moving out to Mars?’ she asked. ‘There aren’t a lot of people who look like us out there.’ And I defended this place to my sister. I didn’t tell her that Durant wasn’t Mars, because most days it feels like a foreign planet. But I told her that I had a right to sail across the universe if I wanted, and to meet behind Mars with my beloveds like Cheryl Lynn sang in 1978.

Jesse’s body is policed, just like Marie, Lottie and Tonya are at school in ‘The Art of Heroine Worship’. The three girls are transferred to a new, majority-white school; Lottie is tokenized as the Ideal Black Girl, and Tonya—much darker than Lottie—suffers immensely from her inability to find a safe space for herself, away from insufferable colourism.

Simms’ protagonists wind their way through alien landscapes, where home is a place unknown or of no return. In ‘The Body When Buoyant’, Nichelle meanders through Los Angeles and works as a homecare nurse. She left for the city after Katrina devastated her home in New Orleans. All she wants is a house, one out of her financial reach—so much so that she presses her face to one of its glass panes and breaks it. All she wants is something firm to hold on to.

Space is also personal, creative. In ‘High Country’ Hathoria examines what it would mean to reclaim her personal space and time in order to write, away from her family. In ‘Dive’ Alexandria thinks about family histories and legacies: as an adopted child, and now a pregnant woman, she grapples with what it means to have familial, ancestral history beyond her non-biological parents, tries to find solid psychological footing.

Simms’ experiments with domestic realism but also fabulism and satire; she has crafted beautifully deep, tangible characters, and their dialogue is some of the best that I’ve read recently. Meet Behind Mars is a collection to be treasured.