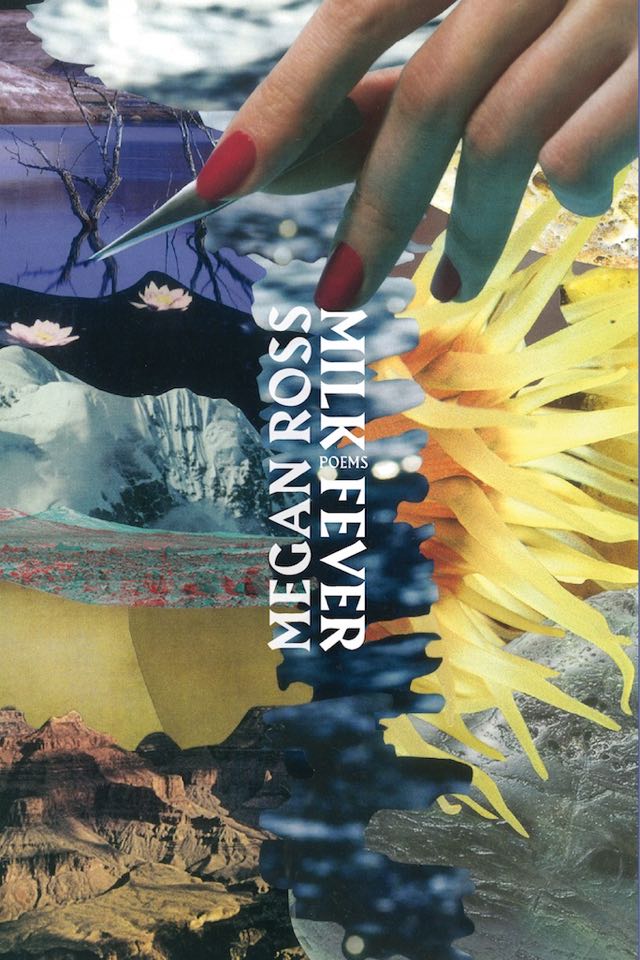

Milk Fever

— Logan February

In Milk Fever, Megan Ross has crafted a document of womanly scars. In her stunning debut, the poet examines the self, girlhood, motherhood, family archetypes, and the essence of the past that lives in memory. Ross’ voice is tender and meek in some places, overwhelming with power in others, but it is rich with vividly-detailed nostalgia and sings with recollection most often.

In the world of Milk Fever, history repeats itself. Ross’ speaker is one who “would always take to mourning like religion.” Across the volume, the poet details a generational record of violence against women, and when the violence makes its way into the speaker’s life, she handles it with a kind of familiarity, saying: “you cracked / my / spine / as you might / a book / you said you loved.”

In ‘Breaking Waters,’ a gutting 3-page poem about the husband stitch—an extra stitch given during the repair process after a vaginal birth, supposedly to tighten the vagina for increased pleasure of a male sexual partner, with painful consequences for women—the speaker bitterly realizes: “I am the blood / of my first blood’s promise,” and the poem ends:

I didn't begin my life

so scarred I grew into

the sawdust doll

by a slow succession

of seams

Milk Fever is an account of the violence enacted upon the bodies of women, as well as their minds—the trauma of abuse, assault, misogyny, and toxic body standards. The volume also documents a difficult pregnancy and birth (“Baby Is Transverse / and I am / an abacus of bone”) alongside issues with post-partum depression:

Skin can accommodate absence

but the womb mourns her loss

marking each hour without

your metronome of kicks

The speaker, however, finds ways to keep herself tender despite the cruelties of the world she finds herself in. Solace is found in the company and support provided by other women, especially the women in her preceding generations—her mother and grandmothers. The book highlights the necessity for women to maintain connections to their feminine roots (in a poem, she reaches for eggs in a refrigerator and intuits a deep craving: “one day I will crack open / and know my yolk”) and to retake their agency, to “embody this pronoun, anagram I.”

“Your milk comes apart so it can be held / like soft frangipanis inking your skin,” Ross writes in ‘Nothing in the water,’ with her skilful magnification of the little details of memory. This is a poet who knows how to distill the past and bring forth a heady concentration of emotion. Milk Fever dwells in the duality of the woman, embracing beauty without shying away from the ugly and true agonies. At the end of the same poem, the speaker vulnerably confides:

How

difficult it is to love like this, knowing loss

is always near; knowing that sometimes,

you are the loss.