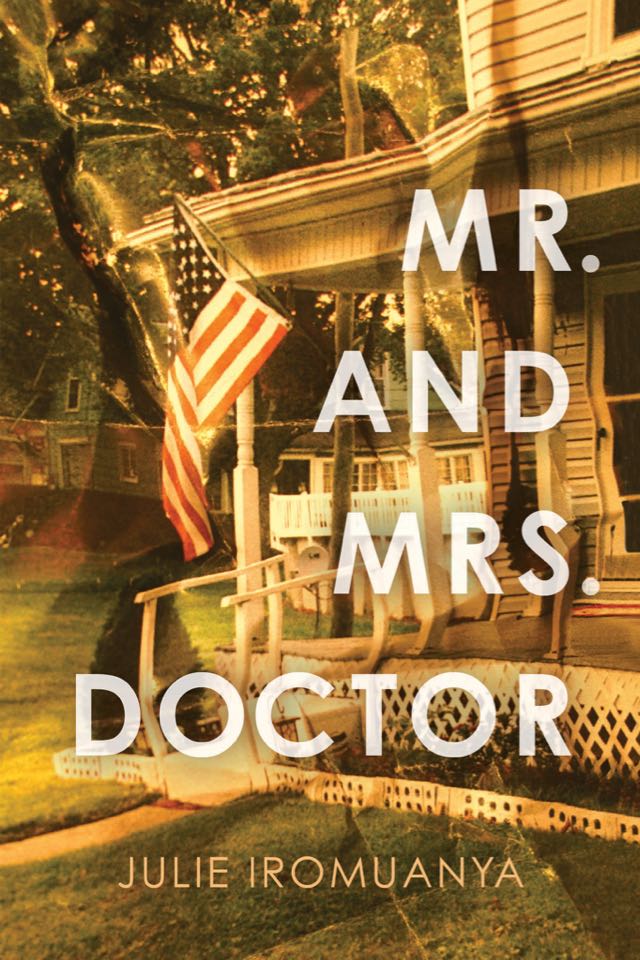

Mr. and Mrs. Doctor

— Ilana Masad

I started reading Mr. and Mrs. Doctor by Julie Iromuanya because I’d been assigned it in my fiction workshop. Iromuanya graduated from the same program I now attend, and our teacher wanted us to read her most successful students’ work. But, because grad school is hard, I only managed to read about half the novel during the semester. In hindsight, I’m relieved, because I needed the mental space I got over winter break to really dive into its emotional depths.

The novel opens with Job and Ifi’s wedding night in Nigeria. The couple’s marriage was arranged—Job, who’d been leading a lonely, difficult life in the US, received a Tinder-like array of photos from his family and was told to choose whomever most pleased him. Ifi, on the other hand, had no choice in the matter; having been raised by her aunt after her parents’ deaths, she was expected to comply with this plan, move to the US with Job, and send money back to her family.

Although the wedding night is somewhat disastrous—Job has only learned about sex through pornography and is somewhat violent with his passions at first, before Ifi very competently fends him off—they do conceive, and by the time Ifi moves to the US a couple months later, she knows she’s pregnant. But here’s the thing: Ifi thought she was marrying a doctor. Her family thought she was marrying a doctor. Job’s own family thinks he’s a doctor. You see where this is going: he’s not a doctor, has never been to med school, and flunked out of college early and has been too scared to go back. He’s a nurse’s assistant at a hospital and carries around a stethoscope that belonged to his brother, the bright young man who was originally supposed to become a doctor but who died young instead.

This lie about Job’s profession is the novel’s central point of shame, but as the plot moves forward, it’s clear that everyone—Ifi, her family, Job’s family, Job’s only friends in the US who are also Nigerian immigrants, the woman Job married for a green card and later divorced—everyone in Job’s life is lying about some vulnerable part of them. While everyone’s lies are of differing scope and tone, all of them are told in service of self-preservation in the form of self-aggrandizement.

A book about a particular kind of immigrant life, the novel is also a commentary on Americanness, a state in which inflation of one’s ego is almost required. The so-called American Dream is a cardboard cutout of a certain type of success largely reserved for a privileged few, and thus it’s an empty box for everyone else. There are no bootstraps with which Job and Ifi can pull themselves up—they’re black immigrants whose accents are misheard as poorly spoken English, and they’re working as hard as they can already.

Why don’t they return home, when America has not only treated them badly, but badly disappointed them? Because they no longer belong to themselves—they belong to their families who’ve entrusted them with a dream that must be carried on to the next generation, to the son that Ifi gives birth to, a son whose very survival in their harsh reality is in question.

A heartbreaking, beautifully sculpted, and extremely thought-provoking book.