Night Sky with Exit Wounds

— Alexandra d’Abbadie

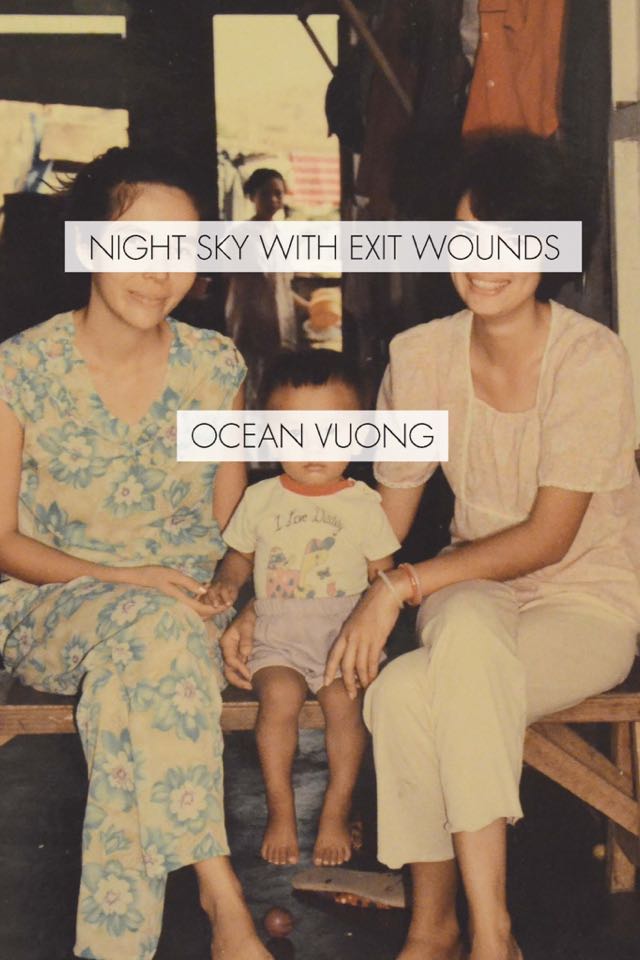

My friends who own Night Sky with Exit Wounds caress the cover in awe, clutch it tightly to themselves before sharing the book with others, give it pride of place on their bedside table long after the collection has been read and reread. Ocean Vuong’s melodic insouciance defines the voice of the moment: this is a man who can write lines like:

An American soldier fucked a Vietnamese farmgirl. Thus my

Mother exists. Thus I exist. Thus no bombs = no family = no me.

Yikes.

From ‘Notebook Fragments’, as well as lines like:

It’s not too late. Our heads haloed

with gnats & summer too early to leave

any marks.

From ‘On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous’. Bloodsongs, verses cut and moulded from intergenerational violence, from war, Vietnam and America. In an interview with Prac Crit, Vuong states that Night Sky is a very American book

and that he writes through the spaces of American identity. The collection grapples with what it is to be a product of such a melding, to write within these spaces.

Vuong has forged an epic out of his family’s intergenerational, intercontinental trauma. Like Walcott’s Omeros (another voyage into identity, grief and reconciliation of the self), he doesn’t just appropriate mythical Greek figures but defamiliarises them, allowing for other stories to take shape. Odysseus is traumatised by war, in Night Sky. The father figure is broken, but it is his voice which bathes his son in music in ‘Threshold’: His voice - / it filled me to the core / like a skeleton

. This music is the birth of this book and perhaps of the poet himself.

Not enough has been written on Vuong’s formidable treatment of 21st century postmodern war: the way traumatised bodies are screened, filtered and endlessly reproduced until they become part of an iconography of violence. The narratives these images have, of course, depend on the dominating powers that be. Take these lines from ‘Self-Portrait As Exit Wounds’, for instance: everyone cheering as another / brown gook crumbles under John Wayne’s M16, Vietnam / burning on the screen, let it slide through their ears, / clean, like a promise, before piercing the poster of Michael Jackson

. The tone here is almost at a remove, mellifluously blasé: violence has become image signifying some kind of foreign entertainment. You’ve also got ‘Of Thee I Sing’ on the Kennedy assassination: Jacqueline’s blood-stained suit is übermedia at this point, her iconography displacing the horror of the Kennedy administration’s actions as an afterthought. Their blood is also on her white glove / glistening pink – with all / our American dreams

.

Vuong brilliantly channels the American dream/nightmare dichotomy in ‘Aubade With Burning City’. His masterful pace evokes the dread stasis, paralysis and slow-mo vision before the killings begin:

A helicopter lifting the living just

out of reach.

The city so white it is ready for ink.

The radio saying run run run.

Milkflower petals on a black dog

like pieces of a girl’s dress.

An eerie stillness set to the horrifying tune of Irving Berlin’s ‘White Christmas’, used as a code before the start of Operation Frequent Wind. The full rhymes of Berlin’s song are eerily abhorrent when paired with Vuong’s verses: a dog’s hind legs are crushed into the shine / of a white Christmas

, The treetops glisten and children listen, the chief of police / facedown in a pool of Coca-Cola.

Vuong’s poems ceaselessly rip into you without ever losing their poignancy. This isn’t new sincerity, but raw being: vicious, visceral life that aches with love, since Night Sky is a kind of ode to Vuong’s family as well as a celebration of the body and its bittersweet pleasures.