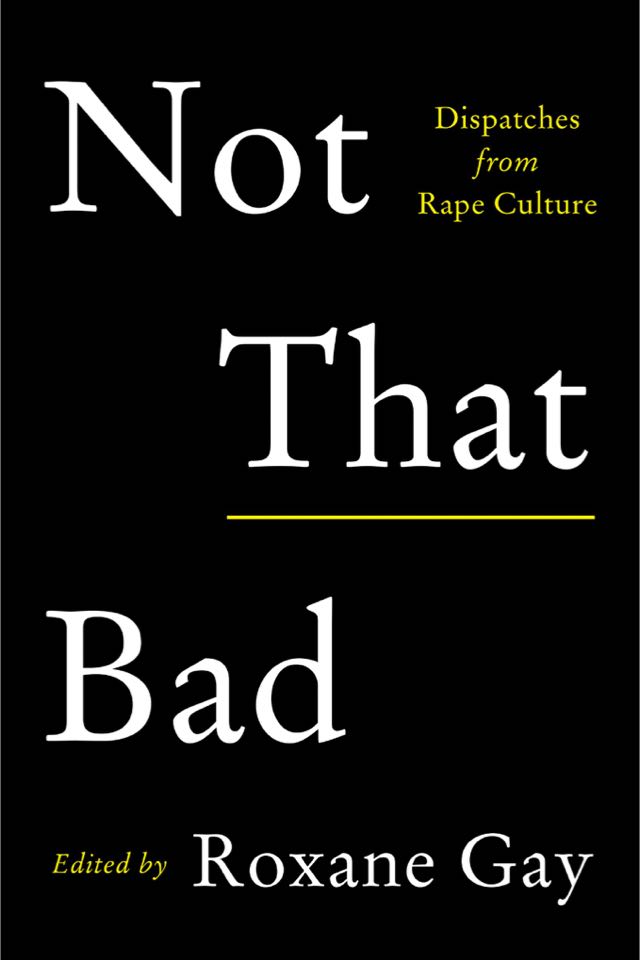

Not That Bad: Dispatches from Rape Culture

— Yael van der Wouden

Warning: This book depicts sexual assault in detail.

Anger is the privilege of the truly broken, and yet, I’ve never met a woman who was broken enough that she allowed herself to be angry.

— Lyz Lenz, ‘All the Angry Women’

One of my favourite scholars is Joanna Bourke. Once, during my BA, I stumbled into one of her guest lectures. It was about the cultural significance of fear and to this day still, one of the best lectures I’d ever been to. The next day I bought the first work of hers I could find, and it was Rape: A History from 1860 to the Present (2007). My plan was read it, all of it, but I didn’t. I put it on the shelf, took it off again when I moved to a new apartment. Put it up again. Didn’t read it. For a while it was something friends would point out when coming to visit—This is Yael’s bookshelf. In case you were wondering where her Austen is, you will find it right next to Rape: A History. It was supposed to be a joke. I probably laughed, embarrassed by either the book or my friends. I’m not sure which.

I would come back to Bourke during my last years at university. I had decided to write a piece on the intersection of law, language, and women’s bodies. I type this lightly, now, ‘writing a piece on,’ but in truth it took me half a year to get through Rape: A History. It took another year and a half to finish my essay. My professor sent back the first version saying: “I can read how much you’re hurting for this topic. It’s good, but it’s not academic.”

For a while I called those two years I spent immersed in academic texts on rape as my “angry years”, unsure of how to explain my sudden depression (and subsequent disappearance from social life) to my friends. Strange, how you can become immersed in the narrative of trauma without ever recognising your own. How you can become obsessed with a topic that triggers the worst of your anxiety, without a shred of reflection as to why.

I left the topic alone, after that. I graduated writing about trees. I left rooms when conversations veered a certain way. Sometimes I stayed but didn’t share, rarely shared, listening to other people’s stories and thinking my own were really not that bad—that phrase, on a loop, the entire time.

I’m not sure what I expected to read picking up Not That Bad. I must’ve known exactly what I was going to read. The subtitle reads, “Dispatches from Rape Culture.” The official tagline calls it an “anthology of first-person essays [that] tackles rape, assault, and harassment head-on.” I guess sometimes you don’t tell yourself what you’re doing until you’re right in the middle of it. I say, ‘right in the middle,’ but really it took me three sentences into the introduction to remember myself, the body that was reading it. It took three essays into the anthology to understand that I was not going to just read this book, I was going to experience it.

Each of the thirty essays in this collection is entirely unlike the one that came before it. The voices are different, and their narratives—when they’re there—are different. The people and their backgrounds and their memories, all different. And yet I found myself in each and every one of them. I found my sisters, and my friends, and my friends’ friends. I found the world I know not just represented in the dialogue each writer creates with an imagined reader—but also in the moments where identification with these stories isn’t the main goal. In the moments that make you take a step back and wonder at your own acts, your own relationships. How do you respond to that one text from a friend, the night after? Do you think she’s joking? What language do you use when you comfort?

Are you comforting?

Are you sure?

That, in its own, was one of the most gut-wrenching confirmations I had while reading Not That Bad: that the shapes and masks that rape culture takes on are endless. That you can think you know its boundaries, can tiptoe outside of it—leave the room during conversations, avoid certain headlines—only to look back years later and realise that there was never a boundary to begin with. You drew it for yourself with a bit of chalk. A circle of salt.

But also I want to say: I have been calling it a collection, an anthology, as though it’s a cohesive unit of essays. However its original subtitle, I think, does it far more justice: dispatches. The notion that each writer, each voice, has its own story to tell that can be related to the others—but not necessarily so. To honour this, I want to close off with a few quotes, a modest selection of lines I’ll be carrying close from hereon out:

If rape culture had a flag, it would be one of those boob inspector t-shirts. If rape culture had its own cuisine, it would be all the shit you have to swallow.

Aubrey Hirsch, ‘Fragments’

I wanted to deny that my body is part of who I am, because it had been used against me.

Elisabeth Fairfield Stokes, ‘Reaping What Rape Cultures Sows: Live from the Killing Fields of Growing Up Female in America’

Here is a list of things that have helped me, in no particular order: […] sometimes I imagine black wings. Specifically, I am lying on my bed at night, on my left side, and I imagine someone climbing in next to me and wrapping long black wings over me.

Zoë Medeiros, ‘Why I Stopped’

My language is so imprecise. I am thrashing in what I can’t tell you.

Claire Schwartz, ‘& the Truth Is, I Have No Story’

I am a hard person because hardness is what comes from life lived underground.

Brandon Taylor, ‘Spectator: My Family, My Rapist, and Mourning Online’

I told my parents […]. Not everything. We learn not to tell everything. We know telling everything will make them see the bad in us.

xTx, ‘The Ways We Are Taught to Be a Girl’