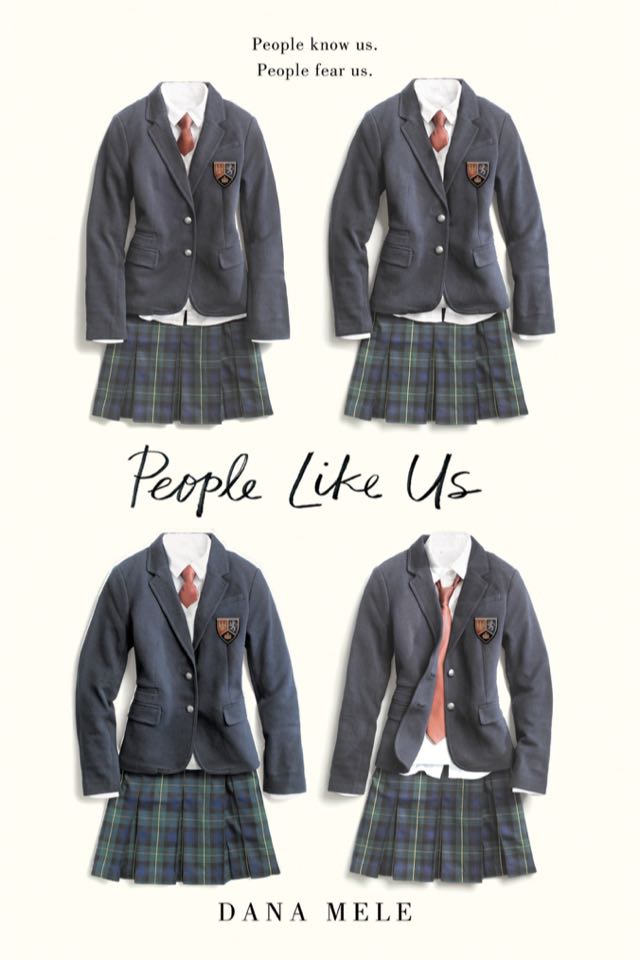

People Like Us

— Yael van der Wouden

At the end of Mean Girls (2004), right after all the girls share their insecurities and crowd-dive off of a stage, Regina George learns of the extent of Cady’s betrayal. She storms off, and when Cady chases after her to apologize, Regina turns around in the middle of the road and delivers a mean-girl-speech crescendo. “You know what everyone says about you?” she asks Cady. “That you’re a home-schooled jungle freak who’s a less-hot version of me. So don’t try to act so innocent. You can take your fake apology, and shove it right up your hairy—”

And that’s when Regina George gets hit by a bus. She doesn’t die, Cady’s narration tells us. Though some rumors say that it was Cady who pushed her.

But what if Regina George had died? What if Cady had pushed her? Or—to take the game in a different direction—what if instead it was Regina who’d pushed someone under the bus? Better yet, what if a reformed, openly bisexual Regina George was framed for murder? At a boarding school?

If that description got a soft gasp out of you, then you’re in good company. That is, my company. Me and my one friend who—when I described Dana Mele’s People Like Us as mentioned above—covered his mouth and mumbled: why haven’t I written that?

Why indeed.

Dana Mele’s People Like Us (2018) follows Kat, popular soccer girl and the ring-leader of her mean-girl gang at Bates Academy. It opens on the night of a Halloween dance, when the group drunkenly barrels their way from the hall to the lake. A step ahead of Kat is the object of her tense love, her best friend, Brie. The image is this: gorgeous girls flashing smiles at one another, about to get up to no good, about to jump into the water. But they never quite make it. In the middle of the lake they find a dead girl, floating in a white ball gown. She doesn’t seem recognizable.

“Does anyone know her?” Kat asks. No one does. One of the girls has maybe seen her around. They call the appropriate authorities: principal, police, security. People show up, ask questions, and somehow—it’s not yet clear how—Kat is not answering in the right way. Or at least, not in the way the investigator wants her to. The oddity of it, the strangeness of having experienced something traumatic—and then not being listened to—is only heightened by how the story is told: through Kat’s point of view. The point of view of, as we find out very quickly, someone who used to be very awful, but isn’t anymore. The story unfolds immediately: before the girl died, she left behind a set of clues in the form of a revenge blog. It’s then up to Kat to follow the rules of the blog in order to keep her own incriminating past a secret. How must Kat avenge the mysterious dead girl? By turning on her fellow mean girls, one by one.

For a long time it’s hard to say, exactly, what Kat and her friends have done to deserve the revenge acts unleashed upon them. Kat herself doesn’t really reflect on the bullying narrative in the way we’re used to hearing—through the perspective of the victim. It’s all a combination of misunderstandings, of things she regrets but doesn’t quite remember doing, or saying. Most of what she does reflect on ends up having little to do with the girls she bullied, and so much more with her own issues: lashing out because of her past, lashing out because she was hurt, or was trying to get someone’s attention. At one point in the story, Kat enlists the help of a girl (Nola) who it seems was once hurt by something Kat did, or didn’t do. Kat herself is unsure until nearly the very end of the story.

At another point, Kat leaves a mean note on a friend’s door—she’s desperate, grieving and sick, and while it’s clear she reverted back to bullying behavior because of her insecurities, it’s easy to forgive her choice as described through her eyes. Her narrative. Then, just a few pages later—after Kat comes back from being on her own tangent of an adventure—she finds her dorm-room door covered in notes, echoing her mean-girl words back at her. How this escalated, why, who orchestrated it—unclear. Kat barely registers it. In her world, the mean things she does are an afterthought, a side-narrative, never the main focus.

And that’s the most fascinating takeaway of People Like Us. Taken at face-value, the novel might only seem like a YA whodunit, fast-paced and plot-driven. But at closer inspection this fascinating novel does a lot more. Beyond the fact that it has bisexual representation—done so, so well in terms of language and self-reflection—that it touches on issues of class and racism, People Like Us complicates the archetype of the mean girl in a way I’ve always wanted to see. I read this book at a curious time: not too long ago Sierra Burgess is a Loser came out on Netflix, and if you’ve followed the release, you might’ve seen the discussion that unfolded around it—about bullying, and what a ‘mean girl’ is, and not unimportantly, the value of saying sorry. Sierra Burgess, if you haven’t seen it, attempted to tell a story where a mean girl becomes friends with the girl she bullies—and then the roles are flipped when the ‘kind girl’ does a ‘mean thing.’ The issue—well, one of the issues—with that movie was that it was never clear that Sierra was that ‘kind’ to begin with. Perhaps a little like Cady in Mean Girls, it was a narrative that seemed to be about the lengths people go to in order to get the attention they feel they deserve—only in Sierra Burgess the movie itself was largely oblivious of the direction it was taking.

Getting to read People Like Us in the aftermath of that movie was like getting a masterclass in Mean Girl theory when at first all you had was a pamphlet. It’s a story that unpacks the narrative, yes, but also begs the question of storytelling—and how the stories we tell ourselves, about ourselves, make our own perception of reality. And how others, with their own experiences, their own hearts and hurts, fit into that.

An absolutely riveting and—did I mention? No I haven’t—sexy read with a gasp-worthy conclusion. Go watch Mean Girls, then read this, then sit back and watch as you revisit your own childhood wondering—who was I?

Best read: while it’s raining, before meeting up with your friends. After meeting up with your friends. With a cup of tea, make sure you’re warm. After watching Mean Girls, and before watching Killing Eve.