Pond Smelt

— Terry Abrahams

For the past few days, I’ve been listening to compilations of Animal Crossing music in order to zone out and, on occasion, calm down. The soft, friendly instrumentals are familiar to me, too, as someone who has spent about fifteen years following the video game series. Listening to these songs make me feel as if I’m going home.

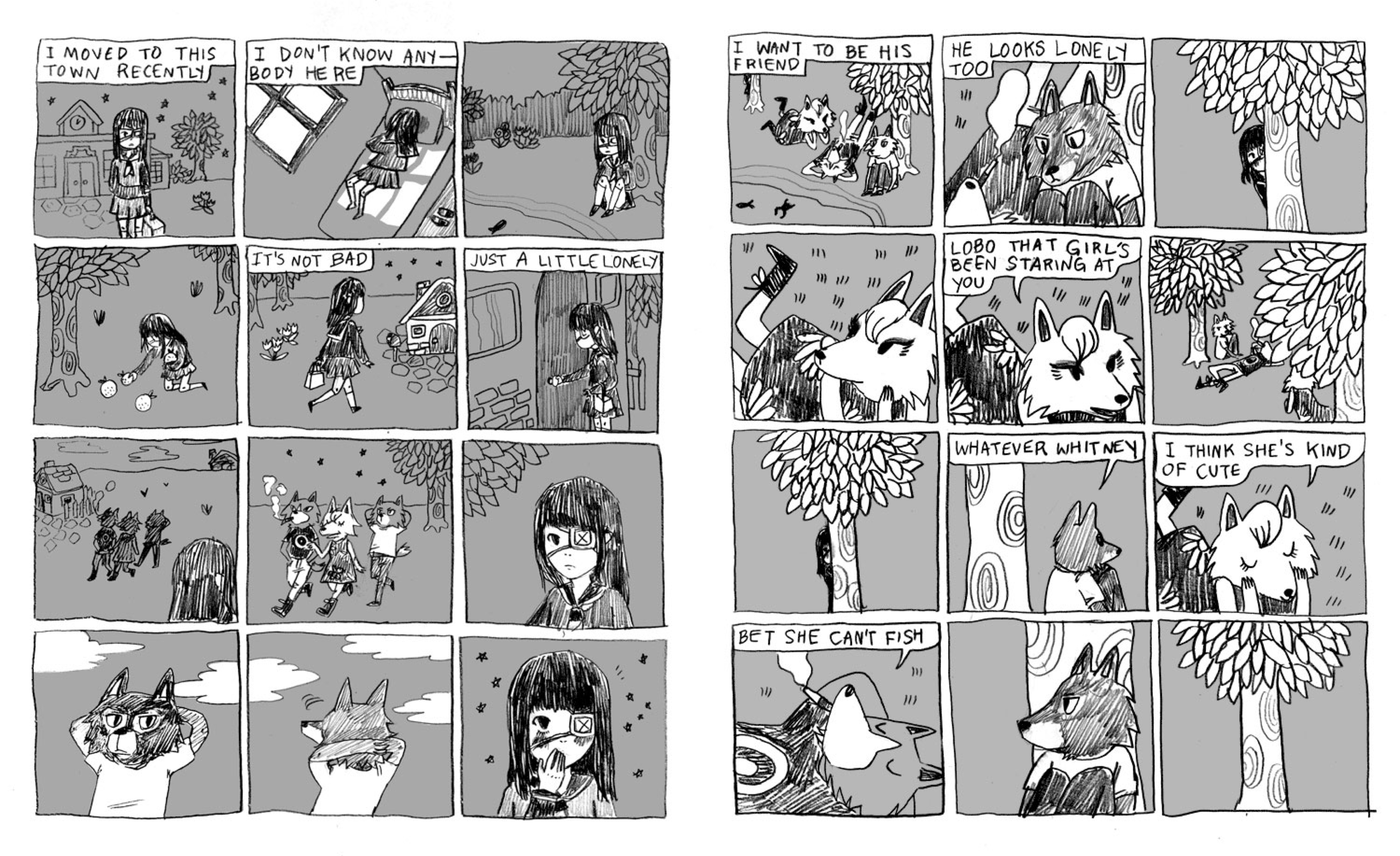

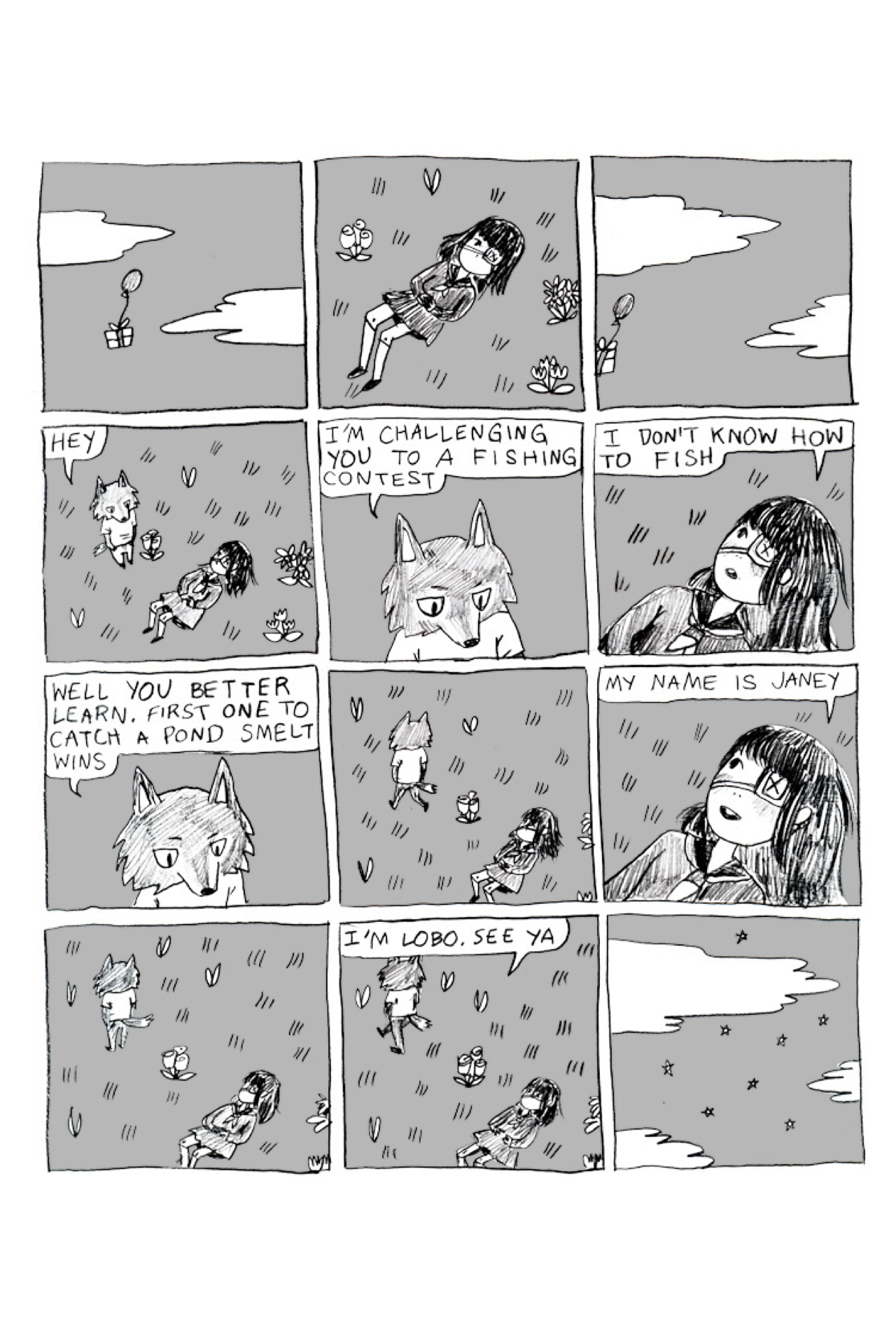

But the music, for me, is tinged with a sense of nostalgia that brings with it more than a few heart pangs. Mai’s short comic from Swedish indie comics publisher Peow! reflects these feelings of pain intermingled with joy and comfort. It follows the story of Jane, who moves to a new town and, at first, isolates herself from her new neighbours. She’s interested in a group of three wolves who hang out near the river, but she keeps her distance. The other villagers remain wary of the wolves, but Jane, undeterred, befriends one of them—a young, down-trodden wolf named Lobo. Their friendship (and hardships) then continue to evolve as the story goes on.

As someone whose other works (including Sunday in the Park with Boys and See You Next Tuesday) are autobiographical in nature, I wasn’t surprised by the emotion that Mai gave to this work. Still, though, the poignant ending comes as somewhat of a surprise. For a game about friendship, fishing, and collecting furniture, the depth of emotion to be found within is as important to encounter and work through as it is difficult to explain. How can a video game make someone cry? As someone who has essentially abandoned their Animal Crossing towns when their life had little time left in it for a second life, I felt that knot of guilt in my stomach grow. Those pixels with personality, with simulated worries, ideas, dreams and opinions, would, it seemed, miss me.

And miss you they do, if you are to return to your town—your villagers will express worry and happiness at “seeing” your return. It elicits a sense of relief, though somewhere in the back of my mind, I know this is all a fiction. However, it’s easy to suspend one’s disbelief and dive right into the lives of these little creatures.

In this same vein, we see Mai adds further characterization to Lobo by having him reflect her main character’s fears. He, too, feels as if he is out of place in the world, despite being an animal like the rest of his neighbours, while Jane, the human, will always stand out. He continuously challenges Jane to fishing competitions for pond smelt, but he doesn’t eat them; he keeps the fish, wanting to, as he says, “surround [himself] with kindness.” In the game itself, villager’s personalities are standardized, and though their dialogue is plenty, eventually, they’ll begin to repeat themselves. It’s up to the player to project further, to create a three-dimensional character out of their pixelized friend, which is a surprisingly (and sometimes dangerously) natural process.

The overarching theme of loneliness and fear of abandonment that creeps onto every page in this comic are the feelings that drove Animal Crossing’s creator to develop the game. Katsuya Eguchi says that the game was borne out of his memories of moving away from friends and family as a young adult to start a new job in a new city: “I wondered for a long time if there would be a way to recreate that feeling,” he told Nintendo Life in a 2011 interview, “and that was the impetus behind the original Animal Crossing.”

For such a joyous, welcoming game series, wherein friendship, community, and kindness are paramount, its origins are somewhat bleak. But among that melancholy is the hope that whoever and wherever you are, you will find people willing to accept and support you. Even if it’s not forever, as in Mai’s work—or in my long-since abandoned Animal Crossing town circa 2003—you were there, you were loved, and that feeling will remain with you a long time after you’re gone.