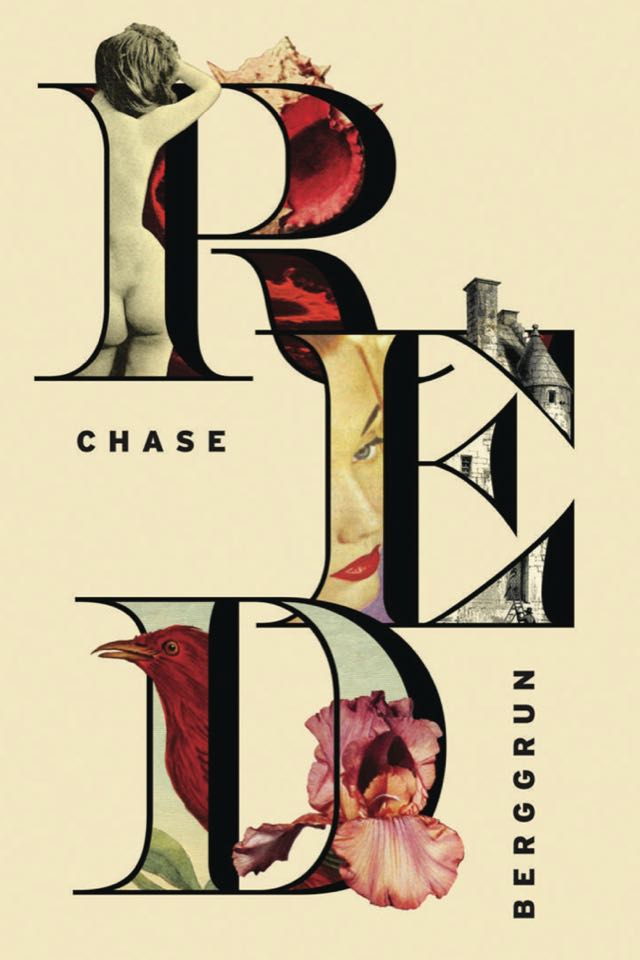

R E D

— Terry Abrahams

R E D is an effort.

To read, to write, to physically have, hold, and work with as well as through. Chase Berggrun’s debut poetry collection takes Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a book “…soaked with a disdain of femininity and the misogyny of its time,” and presents twenty-seven erasure poems in which the narrator is given back her agency, her power, herself. Chapter one begins with an introduction:

I was thirsty

I was a country of queer force

rushing east to see the strangest side of twilight

I was a woman in the usual way

I had no language but distress and duty

Immediately striking, R E D’s narrator, despite the horror she faces, is a striking figure. She moves into her own story at a run and does not slow down or stop. Twenty-seven chapters of her working to escape and eventually overcome her abuser are filled with movement. The writing flows. I cannot say it moves despite its stilted quality, as those short, sharp, sentences, cut from longer prose, only add to and strengthen the fluidity of the work.

Erasure poetry is not a genre I am intimately familiar with, but I know the effort in it is immense. Berggrun completed this effort with a strict set of rules briefly outlined in the collection’s foreword. To create from that which already exists, especially in poetry, can be a tricky and risky business. But Berggrun’s success is obvious. The text weeps with an inarguable originality while never shying away from the integral nature of that which inspired it. Berggrun isn’t afraid to confront their source text—and neither should we. I haven’t read Dracula in full, ever, due to the fact that a) it’s very dense, b) it’s very disturbing and c) through cultural osmosis, I’ve absorbed as much as I need to know about Dracula in order to understand and fully enjoy works such as R E D.

So, yes, we’re aware Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a heavy book in more ways than one. Those thick lines of prose are pared down here, but the meat isn’t made any less satisfying—in fact, Berggrun’s work has made the original, at its most base form, even richer. The language is made anew, and with it, a new story unfolds. This story has no mention of any vampire at all. What exists when Dracula is stripped down, then, is a man—a monstrous man who mirrors in action, word, and being what all vampires are capable of, despite remaining, in this narrative, human. That, of course, is what makes him all the more terrifying.

But caught between the terror, the suspense, and amidst the narrator’s movement against her abuser are moments of striking clarity in observation, notes formulated from thought on other thought:

We never refer to sadness

as something that looks

like secrecy

but it does

To eke out such honesty through subtraction without addition is as riveting in form as it is subject. This being only one of many of its kind, such pieces only show how skilled Berggrun is at their chosen craft. Beautiful, poignant, inspiring, and, despite it all, optimistic in its narrators defiance and will to live, R E D is as assured of itself as it is assuring to read.