Sound of Snow Falling

— Terry Abrahams

I dedicate this book to the Great Horned Owl couples whose lives taught me what it means to be an owl[.]

So ends Maggie Umber’s wordless look at the world of great-horned owls. Charged with careful realism, this book—published by independent press 2dcloud, which specializes in comics—is beautiful. The quiet is palpable, the pacing is perfect, and the glimpse at the life of a pair of owls is all too brief. It is difficult to give a genre to this book—textless, except for the introduction and a brief personal essay from Umber that frame it, Sound of Snow Falling is an experience.

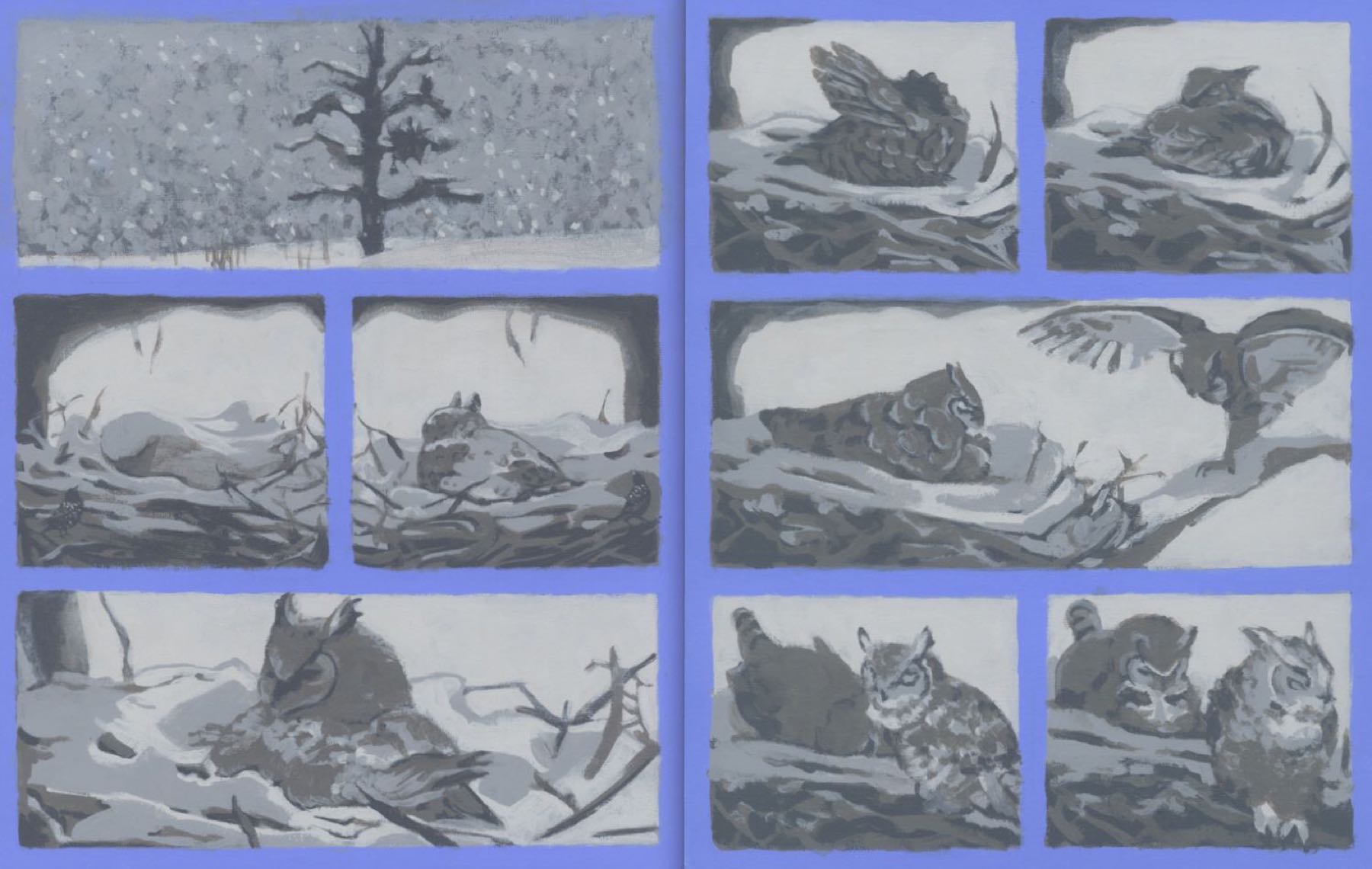

Visual poetry is familiar to many – but what happens when visual poetry loses text altogether? Is it still poetry? I’d like to think so, as poetry is less about content and more about intent. However, poetry comics are still few and far between. As a subgenre of comics, most are self-published, some put out by independent publishers, fewer still formed into being by big-name publishing entities. I don’t believe it as a genre has gained any kind of traction as of yet, but these books do exist. Again, it is difficult to characterize them, but to me, anything poetic takes its time. It’s about images, the slowing down of a moment, of using complex ideas to describe something otherwise simple. Poetry, in an effort to create an image, uses evocative language—or uses familiar language in a surprising way. The series of images, paneled like a traditional comic, create a narrative that would be impossible to depict with just one picture—despite that all-to familiar saying.

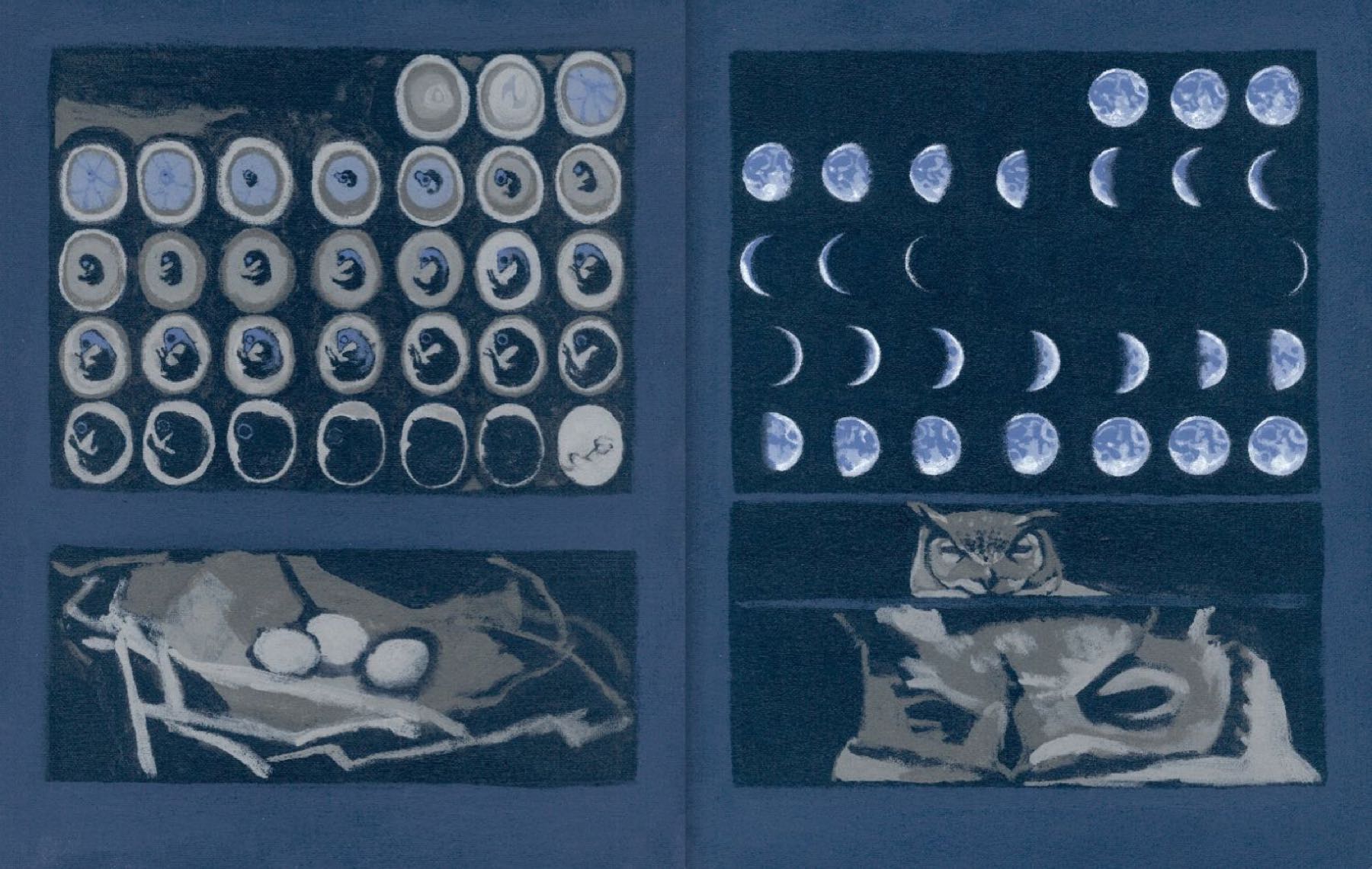

Umber’s careful look at the life of a pair of owls attempting to survive and raise their chicks is akin to a nature documentary, but without the scientific jargon and attempt to educate. This comic allows the owls to just exist. By not offering any explanation for their behaviour, the reader is left with nothing but their own prior knowledge. Perhaps you knew a lot about owls; perhaps you knew nothing. Either way, your perspective on the bird has changed. Most stunning is the page that depicts the waning and waxing of the moon in time with the development of an owl chick still in-shell. The transition of the moon, mirrored by the growth of the chick, highlights the harmony that exists in nature despite all its violence and confusion. But even dubbing the natural world violent

and confused

comes from a uniquely human bias—these words go beyond what most animals, including owls, can comprehend. It is the human that interprets, that creates the story.

Unlike Mary Oliver, an American poet whose idyllic look at nature (including the owl) is an oft-romanticized, very human perspective, Umber’s realism invites the reader to become part of the scenery. Somehow, Umber doesn’t allow room for the human gaze, the biased interpretation of animal life and livelihood: instead, readers are presented with the owls as they are. This way, a reader can be amazed, frightened, moved; they may find beauty or ugliness in the owl’s misshapen nest, or their startling eyes; or perhaps there are even some readers who feel more for the raccoon or the rabbit that are so unlucky as to come in contact with these birds of prey.

A great horn owl growing in an egg as the moon keeps time,Maggie Umber (in a Medium post)

What can’t be denied—no matter your experience of Umber’s careful reflection of the world—is how beautiful the book is overall. Unlike the crystal-clear shots of an animal documentary, Umber’s art is stylized with heavy, often rough brush strokes, and the dark colours cause the scenery and the subjects—the owl pair—to blend together. The effect is immediate—you truly no longer feel like a viewer so much as you do a participant. It’s easy to pretend you are a part of the scenery, easy to be as akin to the owls as you are to the trees, the ponds, the rabbit they catch and eat. The title—Sound of Snow Falling—ultimately ties it back to poetry for me. Umber’s depiction of the silence and grace these birds embody is expressed in this lyrical phrase, something you can only understand after watching the lives of the owls unfold.