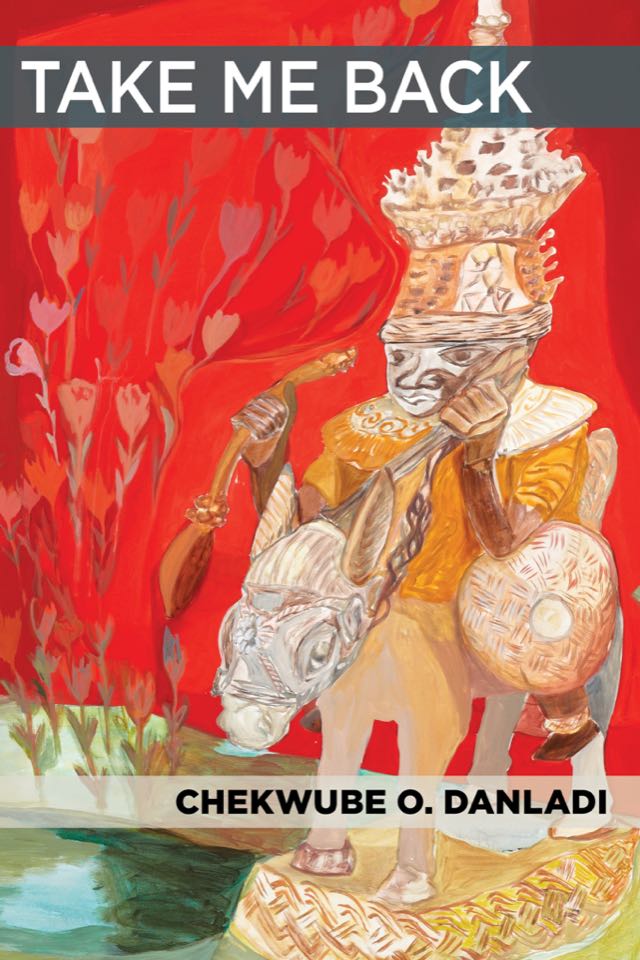

Take Me Back

— Xandria Phillips

Chekwube Danladi’s debut collection of poetry is full of anthems; poems tolling selfhood with unwavering honesty. In their poem, ‘Phenomenology of Excess,’ language fronts for no one while wading through catalogs of essence.

I have three shades of lipstick.

All plum. Fog swirled me on the

way here. And I still smell like wet leaves.

Beyoncé, who I only tolerate,

careens overhead. Liquor has

been tender with me. This night in Chicago,

unrelenting queers do battle. I am

too dark for the studs. Too

femme for the femmes. Only the white

people want to take everything from me.

Chekwube is unwilling to sidestep the margins they inhabit. Idiosyncrasies exist for the speaker alongside a sexual reality haunted by colonial ghosts. Here we see how choice unfolds when there is a deficit of agency.

Some of Chekwube’s colonial ghosts speak. In ‘Leopold II Defends his Philanthropy Under Le Association International Africaine’ the voice of the Congo’s crowned butcher takes the stage.

How can I explain this meat as a blessing?

A tracheal cutting. Minced sacrifice.

I am a giver of cauterized nubs.

Compatriots, feel free to call me a hero.

And the rubber is nothing. Rite. Good feeling.

Wealth. I give the earth new limbs to knead

sacrifice. Collagenous tissue percolated in muck.

Weak carcasses a dark cutter.

Atop his podium made of blood and gristle, Leopold confesses his imperial triumphs. The soil beneath his feet is red. Chekwube marks an inescapable truth by refusing to divorce the human being from the mythology built around him. Chekwube’s work is relentlessly layered in that everyone I encounter in the book feels linked to the past and simultaneously consumed by the present. Everyone, even the long-dead, feel simultaneously close enough to touch, and expansive enough to never fully know.

In their poem ‘I Used to be Called Olivia,’ Chekwube excavates an old comfort.

I dug my own unbecoming, as much as you:

Thirst became ritual, the wallop of

water soaking into the earth, myself wafting off as dust—

an openness invited inward—blue and, enough.

I imagine childhood a swamp,

wet, my small self, nappy hair

doubled with cockleburs,

easy name lilting—spineless and clean—

much suckling the shame quickly,

new abode forming, holding.

What could be more brave that entrenching oneself in the filthy mire of comfort? The landscape of the former self is a treacherous one, and Chekwube tends to it with the spirit of someone who can no longer compromise, even for the sake of their own emotional safety. This is not a self-drag, but a parsing and pulling of poison from sustenance.

The poems in Take Me Back urge me to rid myself of the colonial masters that smile back at me when I look in the mirror.