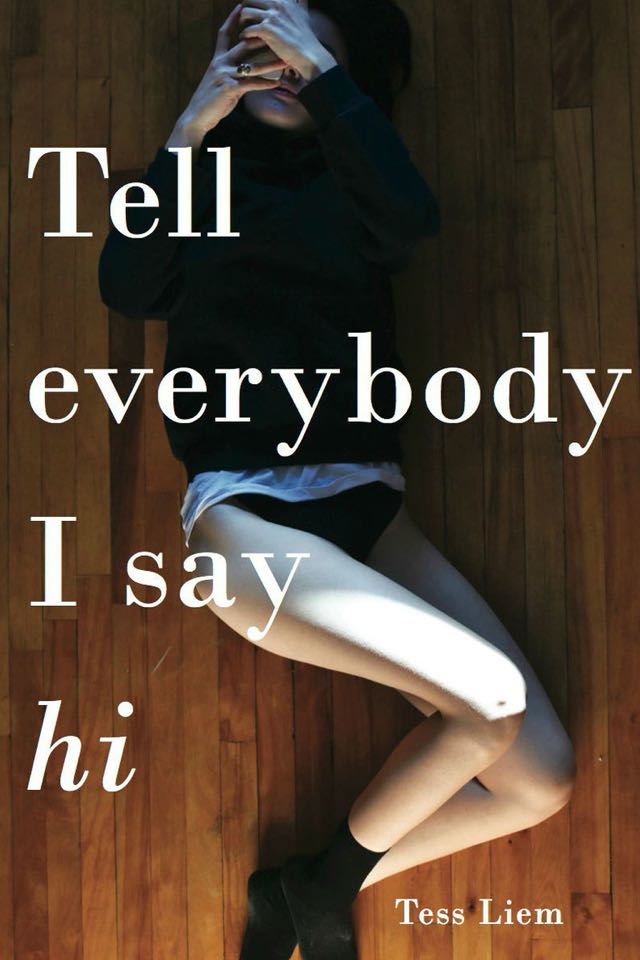

Tell Everybody I Say Hi

— Terry Abrahams

Tess Liem’s writing isn’t so much an answer as it is an unstated question. These poems dare readers to question themselves on a level they haven’t really ever done so before. In short, if you relate to Liem’s narrator, you might have some thinking to do. While drawing from the deeply personal, the feelings Liem pinpoints are, in many ways, universal—but it’s the specifics within that caught my eye. In this all-too brief chapbook, Liem turns the focus inward: here, the intrapersonal abounds. From quiet contemplation to loud internal proclamations, Liem’s writing is intensely human.

And to be human is, in part, to make note. List poems accomplish this by breaking away from free verse, working to read less like poems and more like thought processes (though the two are already remarkably close). In ‘New Superstitions,’ Liem writes reminders, quick and a little sad, but the most striking is the final one listed:

write a note to yourself

I, too, am capable of being unkind

like a wasp

There’s something haunting and important, I think, about realizing that you yourself can be the cause of hurt, of harm—and it takes a more striking tone when included in an otherwise innocuous (but nonetheless touching) list poem.

That being said, let me make it clear: Liem’s narrator isn’t afraid to address themselves, to be open to their own interpretations, reactions, thoughts, wants, actions, emotions, everything. Unafraid and unabashed, the narrator recounts moments with clarity. In ‘Handful,’ the narrative takes us on the same journey as its characters, feeling as though we are getting caught in the rain after going to a friend’s apartment to water their plants, too. But Liem makes us pause as the narrator turns inward: The gap between expectation & what the rain felt like on my face / was hysterical.

This is a feeling only Liem’s narrator can completely understand: it doesn’t need to be explored here. It will live on only in memory, one that the reader was privy too, but didn’t entirely share. Like a good friend telling you a story, some part of it will always be just out of reach.

There’s a domesticity to the poems, too, a yearning for the simple that’s so often out of reach in our lives; in ‘Everything I do is political, especially when I stay home,’ Liem’s narrator brings our attention to the situation of being a body, queer, woman, or otherwise politicized:

& so when I stay home

everything I do is political

because I’ve been reading

about the ethics of space & because

sometimes I lie on the floor

until you text me asking me why I’m not out

& because sometimes we have sex

with most of our clothes on.

The return to the domestic scene of shared intimacy is a reminder that the politicized body is still just that: a body, and sometimes, a body needs to lie on the floor instead of facing a world where it might not be welcome. Liem’s poetry is a welcome reminder that sometimes it’s fine to take some time to yourself. Lie on all the floors, ignore all the texts, question all the facets of your life, and revel in the day-to-day act of being a being.