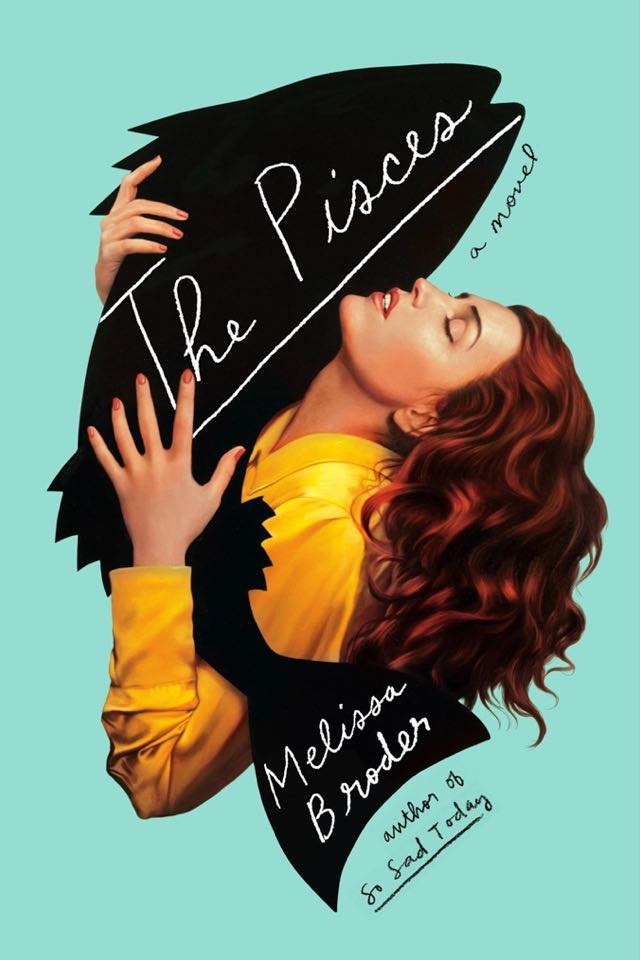

The Pisces

— Ilana Masad

Melissa Broder is well-known to many from her Twitter account @sosadtoday as well as her books of poetry. She is perhaps one of the most relatable writers out there, in that she’s put her depression and anxiety on display for the world to see, and for many of us to relate to with our own experiences. With her debut novel, The Pisces, Broder manages to do something even more impressive: showing us the deep, dark, almost evil side of mental illness as well as the poignant, painful, and relatable side.

Narrator Lucy has just broken up with her long-term boyfriend, Jamie, when the book starts. It was a spur of the moment decision, an almost accidental breakup, except that it really wasn’t, as she was feeling off about him for years. But after the breakup, she begins to feel her depression and anxiety far more acutely than she had before, and the results are intense and scary.

Lucy travels to LA to dog-and-house-sit for her big sister, Annika, and begins attending group therapy sessions for women with sex and love addictions. She’s judgmental of the other women, harshly so; she calls one of them Chickenhorse, because her head was long and horse-shaped but she had a beaky nose and big, pink gums that resembled a chicken’s comb and wattles.

(30) Another woman, Sara, was not only sensitive to men, but also to light, cleaning products, mold, pollen, gluten, dairy, and sugar. She had fibromyalgia, chronic migraines, and, as a result of her hypoglycemia, was given special permission to eat during group. She says that made the room more of a ‘safe space’ for her.

(31) Lucy’s judginess, her derisive tone, is grating at first, but it’s also the way the inside of so many minds work, and is painfully honest. Later in the book, Lucy clearly states several times that her judgments are a way to feel better about where she’s at and who she is, even though really, she has no idea if she’s better than any of these people.

While Lucy is trying to recover from her breakup, she also attempts to sleep around—it isn’t a satisfying experience—and work on her PhD dissertation about the spaces in Sappho’s poetry. Using these spaces as a kind of metaphor for the existential void, Broder deliciously examines the way critical thinking can sometimes be a great comfort for depression, a way to understand it: That was the sad part of Sappho’s spaces,

Lucy narrates. Where there had been something beautiful there before, now they were blank. Time erased all. That was the part nobody could handle… Everything dissolved. No one really wanted satiety. It was the prospect of satiety—the excitement around the notion that we could never be satisfied—that kept us going. But if you were ever actually satisfied it wouldn’t be satisfaction. You would just get hungry for something else. The only way to maybe have satisfaction would be to accept the nothingness and try not to put anyone else in it.

(106)

There’s another central element to the book, a strange, supernatural romance—but, amazingly, it doesn’t take over. The novel is about the isolation of depression and anxiety, really. About how no matter who or what loves you, it doesn’t feel like enough. It doesn’t fill that void, though you wish it would. It’s a powerful work, one full of extreme #feels, and will surely hit home for a great many of us.