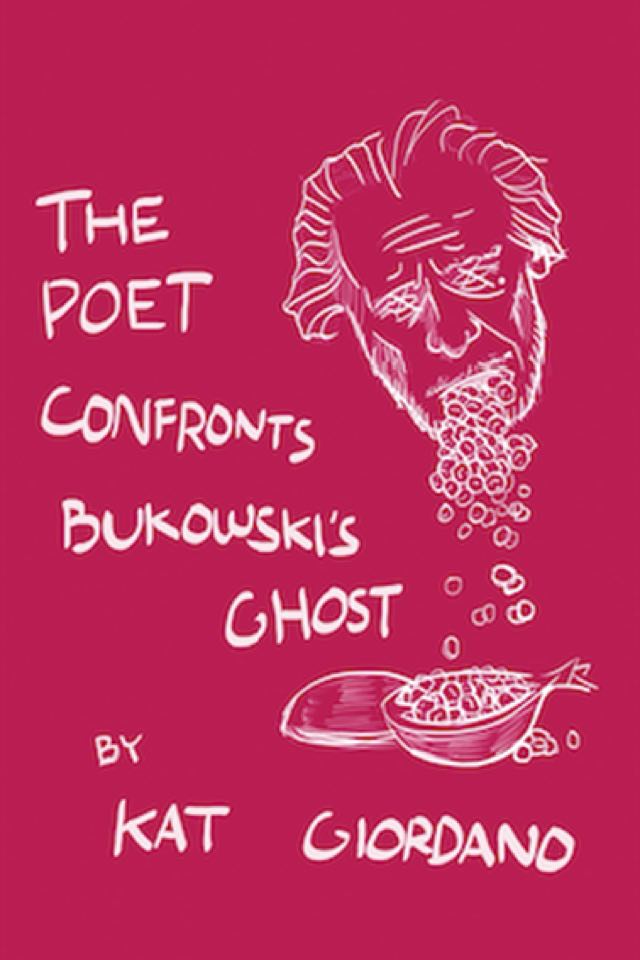

The Poet Confronts Bukowski’s Ghost

— Yael van der Wouden

POETRY IS NOT SELF-EXPRESSION

i mostly write poems because stripping naked and having

you all stand in my bedroom and watch me scream at the ceiling seems like too much of a logistical nightmare.

So I got to read this collection sat on the rocky shore of the Vilnia river: with two feet in the water, while someone’s child was banging on an old piano that had been left on the shallows further down the stream—as an art instillation. And there you have it: on one hand the gorgeous calm of the stream ahead of you, and on the other—a totally absurd and definitely annoying situation distracting you throughout the entire ordeal.

Kat Giordano’s The Poet Confronts Bukowski’s Ghost is woven around a very similar contrast: the one between the heartbreak that comes from words that feel like truth, and words that shape truth unintentionally. The first poem of the collection, titled ‘Style’, prefaces the collection in a way that can only be appreciated in retrospect. it’s true what Bukowski said about style –,

is the opening line, it really is the answer to everything.

Then, a little later:

life may be precious and short and singular

but style is holy, a smoke bomb in my boat

to be set off only when the time is right,

something symbolic, or maybe televised.

That way, it’ll count.

Style is holy, a secret weapon—a distraction mechanism, a smoke bomb, something that operates with fanfare and deserves every ounce of attention it garners. And that’s where Giordano’s work is incredibly clever and delightful and honest: this ode to style with which the collection opens is then upended, questioned, pulled apart and put back together. The moment that truth is organized it becomes a lie,

is the title of another poem, which opens like this:

- I’m worried this isn’t even a poem.

- Fuck it.

- Writing a poem like this feels a lot like taking one of those online personality quizzes. Whenever I lock in an answer I can’t help but predict exactly what the quiz means by its question, leading me to pick the answers that represent the result I want, rather than the Right Answers, which in turn defeats the entire purpose of taking the quiz in the first place.

And with all the charm and wit and seeming effortlessness, the reader is pulled into a nest of question marks: style that goes off like a smoke bomb, a title that negates the truth of it all, and then the content itself—truthfulness embodied, anxiety and internal dialogue and a confession, all in one. What is the reader to believe? Who is the reader to follow? Bukowski’s dedication to style, Giordano’s trickster-like use of it, or the truthfulness in words woven through it all?

The poem titled ‘Relatable Memes’ starts with, when you wake up every morning in a glue trap that you laid yourself.

Another one, ‘Love Doesn’t Exist, Change My View,’ opens with—because i’m still writing about you.

In another one, the narrator imagines a brief love affair with Owen Wilson—whom they ran into on the street—and features earth-shattering lines such as:

and we’re sighing into each other’s mouths to drown out her voice – me, a jammed-up printer; him, a Dyson vacuum.

Or:

I fiddle with the brass knob of his jeans but then his phone goes off. He lets it vibrate in his pocket against my forearm a few times and then answers, and mostly nods a lot, and then hangs up. Pixar, I say, knowing somehow. Pixar, he says. They’re thinking about Cars 4, he says, and they want to meet with me now. I say I understand and he drives me home but by then it’s too late to call you, so I just sigh myself to sleep.

I belly-laughed at this one. The child that was still banging on the broken piano stopped for a brief moment, that’s how hard I laughed. And yet—and yet, more than just momentary laughter, something underlining this poem stayed put.

It sat with me, I couldn’t shake it off. For days I’ve been going over this, this idea of how specific cultural references edge their way into reflections on truth. What Giordano does is invite us, readers, into a very intimate world of a deeply intimate experience—an experience that is contrarily often shaped by the collective, by the media we share, the videos that we make go viral. What this makes is a curious and personal little room that is painted with open spaces, with public spaces—bus-stops, memes, Owen Wilson, Jesus at a bar whispering that He can turn water into wine, His one-off gimmick bar trick / that He thinks will let Him take me home.

Truth is presented as a beating heart with the one poem, and with the next as something that couldn’t ever be portrayed through poetry. Something illusive and perhaps not even real, something that can bend or be used as a tool for the sake of form—of style. That smoke-bomb, that magic-trick.

You’ll laugh at the joke of it, but when the smoke settles, what’s left behind—I can promise—will not leave you alone. It’ll walk with you for days.

Best read: with two feet in the water, with someone else’s idea of music playing in the background. While walking and then stopping because you have to take it in. Out loud at a bar to your best friend, who will laugh, guaranteed.