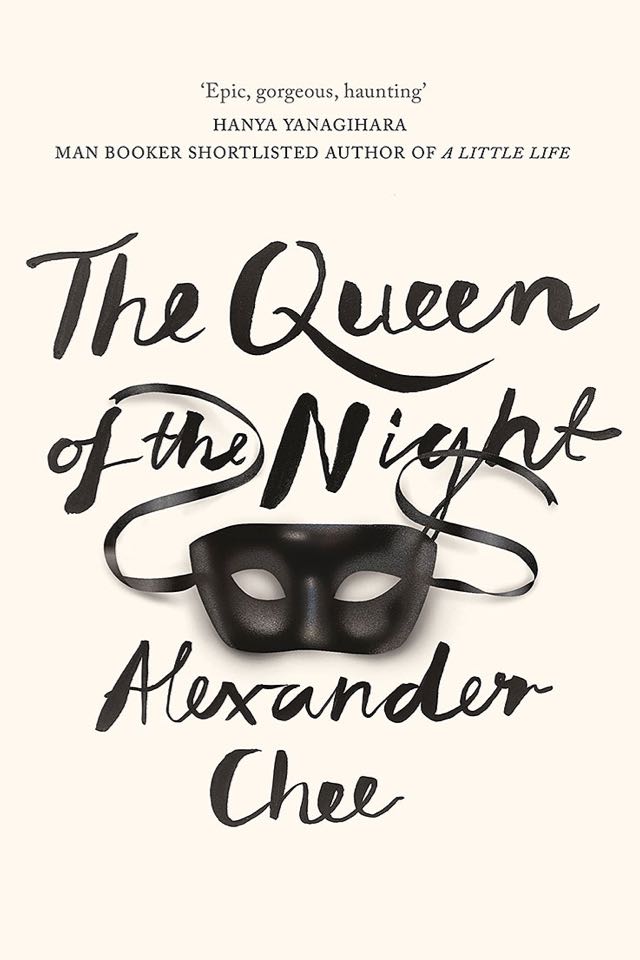

The Queen of the Night

— Alexandra d’Abbadie

The Queen of the Night is a masterpiece. It is exceptional in its genre, immaculately weaving history and narrative until they are of the same thread. Not for a single moment does the voice of Lilliet Berne stray, not once does it seem out of character, context or time. Her ‘I’ pulls you in and never lets go; she is a triumph, a woman the reader will look for each time they visit Paris—I know I will.

Genre is important, since the historical novel is truly a difficult beast. It demands relentless amounts of research, and then asks that this research be somehow brought to life. The novel should be accurate but not dull, meticulous but not overburdened, true to its epoch yet accessible. In the midst of these near impossible, tightrope walker constraints, you’ve also got the novelist’s concern with form: how does action unfold, when history holds no surprises? All this, and in the best instances, the roman should possess the reader so utterly that they never want to leave the book. I’ve found myself delving back into French history, learning more about the opera and its famous sopranos. And so, the novel lives on.

Alexander Chee has produced a triumph, a story as dramatic and exuberant as the operas in which Lilliet sings, a novel that soars. Set in France’s Second Empire and its aftermath, we feverishly read the story of a girl whose life unfolds in extraordinary circumstances. Extraordinary, but never for a second illogical: this is a period of great changes and migrations, where heady, rich life courts scarlet death on every corner. A period where one’s dresses carry enormous import; where lives are toyed with as in a gigantic, whimsical game of chess; where an Emperor’s mistress can stop and start wars as she pleases. It is difficult for me to write a review and not give anything away—I want every reader who picks this up to be as swept away as I was.

The Queen of the Night demanded 15 years of research and writing; the novel shows this, of course, but it is so fluent that you are taken in without a second thought. Just look at the opening line, for instance—look at how graceful it is, and how strong:

When it began, it began as an opera would begin, in a palace, at a ball, in an encounter with a stranger who, you discover, has your fate in his hands.

Never once is the novel bogged down in detail: many, many dresses are described, all of them a pleasure to read. Take the first, for instance:

The dress was a Worth creation of pink taffeta and gold silk, three pink flounces that belled out from a bodice embroidered in a pattern of gold wings. A net of gold-ribbon bows covered the skirt and held the flounces up at the hem. The fichu seemed to clasp me from behind as if alive – how had I not noticed?

I was particularly impressed by the novel’s intricate plot: you think you’re somehow caught up in Lilliet Berne’s underclothes, as it were, since this is of course her story. Gradually, you become aware of the tulle, the stitches, the darts and the lining, until you’re staring at her and history in the face. It is grandiose.