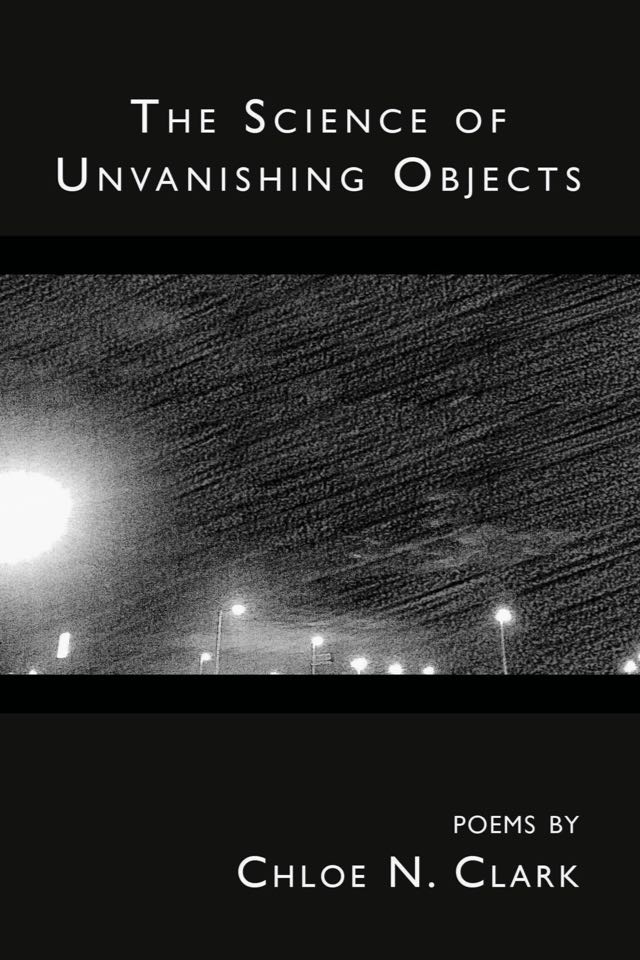

The Science of Unvanishing Objects

— Yael van der Wouden

I have a handful of people in my life that I speak to on a weekly, if not daily basis. People that I update on what I’ve had for dinner, the bird I saw that day—and in turn they do the same, keep me posted the dog they almost pet. And though these people are the closest in many ways, there’s a lot that gets lost in that proximity: you don’t have that let’s-catch-up-on-the-last-5-years moment, that big reveal moment about who you are. And then, once in a good while, something aligns: you go for a walk together, or get drunk or have a nice dinner, and this person that you thought you knew inside out suddenly opens up in a whole new way, adds another layer of intricacy to themselves. And you fall in love all over.

And my apologies for this lengthy introduction, typed out only in service of saying: reading Chloe N. Clark’s collection of work was, for me, much like that. With every new poem I thought I had understood her full capacity as a poet, as a storyteller, and with every new little world she’d crafted I had to go back—revise what I thought I knew, and fall in love with the artistry all over again.

In The Science of Unvanishing Things, Clark has collected the torn edges of genres and sewn them together. One poem delves into the lore of missing girls and the next plays with error messages and memories; one is a conversation overheard on the bus, the other investigates notions of loss and basketball. Ghosts and oranges and devils dot the collection, leitmotifs, making the reader page back and forth to make sure—did they get the reference? Where did they see this word before, this sentence, this thought? One of my favourite poems of this chapbook, ‘Google Search History, Tell Me Who I Am,’ was brilliant on first read—funny, clever in a way that caught me by surprise – but only showed its full depth retrospectively. It starts,

sheed coach

Why isn’t Sheed a coach?

Stats for Rasheed Wallace’s time as Assistant Coach

Andrew Lincoln Abraham Lincoln

When I was a child I thought

What color are cubras?

What color are cobras?

myself foolish for believing

Can I feed my sour sugar?

What will happen if I feed my sour sugar?

What will happen if I feed my sour dough starter sugar?

that someone lived inside the mirror, waiting

How many people have broken their teeth testing gold?

to get out

On face value alone, this poem already does a lot: it uses humor to peek behind the scenes of the writing process, the googling, the googling, the distraction within the googling—the random thought that comes and pulls you into a rabbit hole of information. But beyond that, it’s also a reflection on fear and self fragmentation (sometimes the mirror flickers / […] sometimes I think I’m the one / […] I’m the one looking out

), and how that, too, is also wrapped up in that process of writing. The poem continues,

Fibonacci sequence illustrated in nature

I’m scared

Sounds under water

I’m scared

Of darkness

Where does the word darkness come from?

Words for shadows

that this is all we are

Pictures underwater viewing the sky

But as you make your way through Clark’s collection, titles and fragments jump out at you: a poem about Rasheed Wallace, the image of a mirror again and again, a character explaining the Fibonacci sequence to another. The search keys that broke up the poem in the first place, end up tying the whole work together. The missing girls from the opening poem remain missing throughout the work, only to be found, in one way or another, at the close. The ghost from the one poem is haunting another poem. And that’s how Clark’s poems work: brilliantly on their own, and ingenious in orbit.

Best read: on weekend mornings, with the window open. Out loud, to your best friend with whom you haven’t had a good talk for a while now. In order and then out of order, paging to and fro as you go.