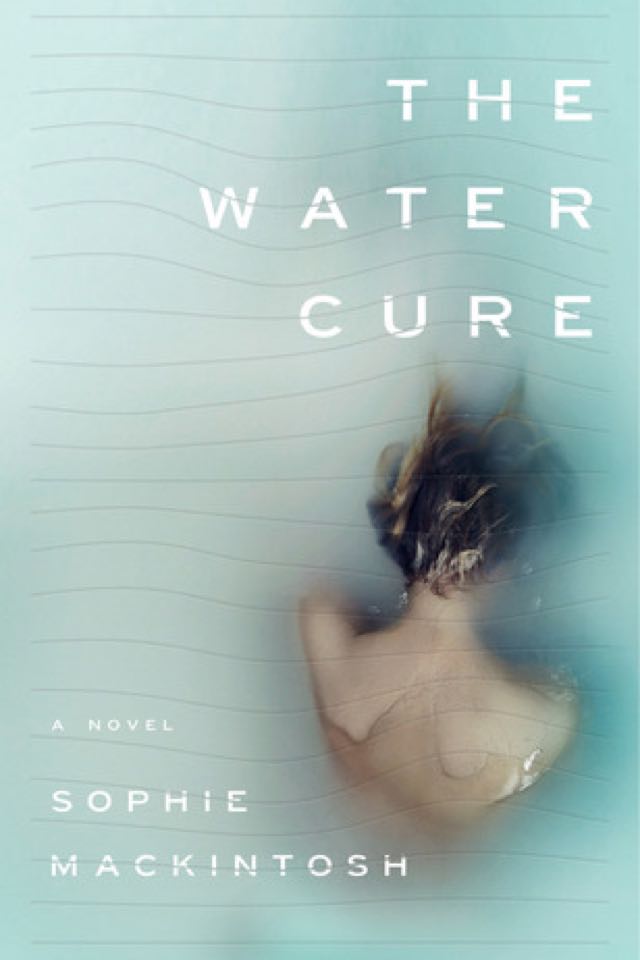

The Water Cure

— Ariel Saramandi

There it was, on the Man Booker longlist—the novel that I had to stop reading several times, so excruciating it was in its affect.

Quite a few people, I believe, can whisk through G.R.R Martin’s grotesque depictions of beheadings, flayings and so forth—their number alone makes these acts almost ridiculous, a death on every page. Skilful depictions of pain—the kind that will leave you ill, haunted—are another matter entirely. I like to think that I’m somewhat hardier than the average reader, specialising, to an extent, in the literature of agony. 4,000 words or so devoted to torture, silence and apartheid in J.M Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians. 15,000 words on German Enlightenment and Romanticism, twin schools of thought that (perhaps) shaped Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow—a dissertation on the novel’s portrayal of the Holocaust. The wielding of pain in fiction is a difficult art; offer a deluge of pain without hope and your narrative is branded as ‘torture porn’ (such as the second season of The Handmaid’s Tale, for instance). Offer too much pain for the sake of it and your narrative seems trite. There is no correct formula, of course—what is ‘too much’ pain, anyway?—but extreme pain is particularly difficult to get right, in fiction (and don’t even get me started on those who appropriate other culture’s pain to exoticize their narrative). You recognize its masterful deployment almost immediately. This is only Mackintosh’s first novel, but her talent’s already fully-formed; a debut that places her among literature’s most exciting new voices.

Waiting for the Barbarians is perhaps a good place to start when thinking of The Water Cure. Both novels take place in unnamed places, unspecified times, though they are imbued with the trauma of real history: apartheid and imperialism in the former, the overwhelming cornucopia of patriarchy’s control and torture of women’s bodies throughout history in the latter. Their surreal-familiar setting, their measured, precise prose exacerbate the characters’ pain and desire, their struggle for redemption and freedom. It goes without saying that they are both exquisitely well-written. I mean:

My body, King said, was the sort that would attract harm, the sort that wouldn’t last long elsewhere. But he really meant my feelings, spiralling out from my chest like the fronds of a sea creature in toxic waters, defiantly, uselessly alive.

The story is narrated by Grace, Lia and Sky, three sisters who live on an island with King and Mother, their parents. The latter have indoctrinated their children to believe that the air is full of toxins that would kill them; they torture the girls, telling them that such ‘exercises’ will exorcise them of all emotions that could make them weak (besides familial love, of course). They are sewn into fainting sacks, made to kill the animals they love. King disappears; Mother continues King’s rule until one day she too goes missing, upon the arrival of strange men on the island’s shores.

The story has the spirit of a lucid fever dream, a timeless fable, though its concerns are deeply anchored in the real world. King and Mother are metaphors for patriarchy, but they operate beyond metaphor too, as characters in themselves. “The family unit twisted into something awful but still recognisable”, Sophie tells me in an e-mail. Similarly, though you can read the sisters through mythology—the Greek moirai, for instance—they are not elevated into myth; they are painfully, all-too-recognizably human, and they find their salvation in each other.

Water as renewal, birth, suffocation, death, isolation, struggle, healing. Multitudinous, like the way a woman moves through the world, the way the reader enters the text: a body submerged in freshwater, in lead-heavy liquid that erases all sound beside your own heartbeat.