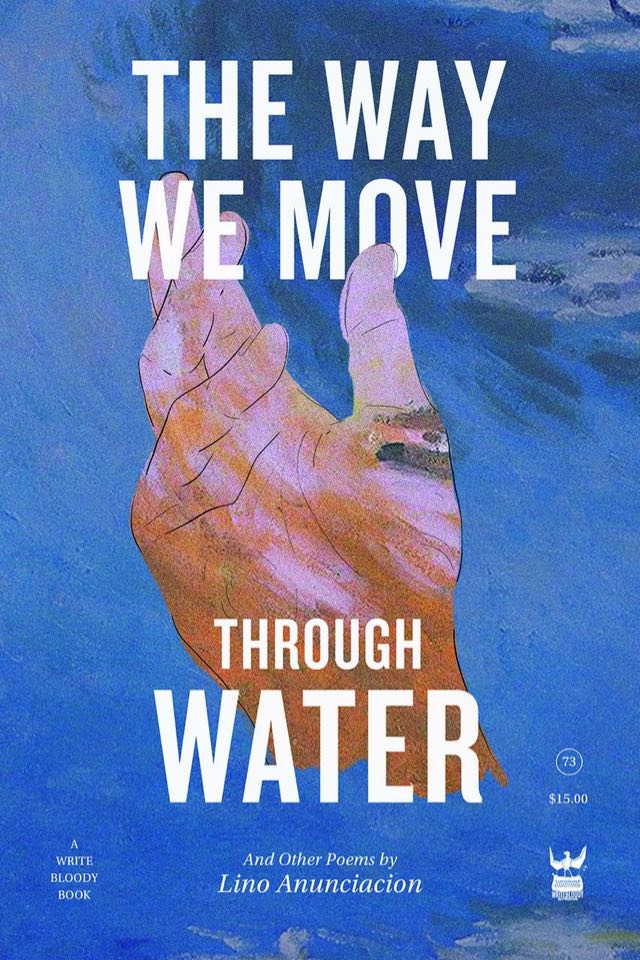

The Way We Move through Water

— Nicholas Nichols

I’m a sucker for black boys and flowers—the way they are both soft yet relentless. Lino Anunciacion’s debut collection, The Way We Move Through Water, is just that, a budding flower. In it, Anunciacion balances the violence inflicted on the black body with the interiority of that body. The collection’s epigraph is a quote by Hanif Abdurraqib—“I, like so many of you, am now looking to get my Joy back, after it ran away to a more deserving land than this.”—introducing us to our first desire, joy. Can a black person find joy in this life? Will the tree ever be just a tree to the black imagination? Will the splendor of God ever make up for this life? These were some of the questions I couldn’t help but ask myself when reading this collection.

Black Nature, an anthology compiled to showcase the the deep tradition of nature poems in the African-American literary cannon, provided a looking glass into the sometimes fraught relationship the African-American poet has to nature. Anunciacion writes:

I too | have sent my love in the form of silence | but never in the form of floods | if crying is the ritual | water is the prayer | but I don’t feel clean | and neither should you | | amen |

Anunciacion utilizes nature as a bridge to God’s attention and, sometimes, neglect. Either the black body is hung on a tree, drowned by a flood, or immortalized by a bouquet of flowers—the body returning from which it came (as Ecclesiastes 3:20). The first third of the collection is named Navy which orientates the black body in a history of violence and offers the idea that, perhaps, we do have to free ourselves of our earthly vessels to find real and lasting joy. Their voice is strong throughout and doesn’t hold back on the violence enacted upon the shared black body, while also establishing that the same abuse is committed upon nature all the time. How can we see ourselves free if we still subjugate the earth?

In the next section, Violet, grief is explored through the relationship between POC and America, but, perhaps more provocatively, we’re introduced to the idea of survivor’s guilt. In ‘How Do You Grow up Older Than Someone Who Died’ the narrator is in a position to justify the life of a young poet who is questioning why they get to live while someone else doesn’t. The poet explores the conceit that to not push on is the only option, that the fate of the oppressed and oppressor are intertwined. At this point in the collection, my attention is drawn to the symbiotic relationship we have with nature. Is America doomed to repeat its destruction of POC in the same way it destroys the Earth?

The final section, Gold, reintroduces us to the narrator we caught a glimpse of towards the end of Violet. What do I mean by, reintroduce the narrator? Hasn’t the narrator been present this entire time? Yes and no, we have seen throughout a talented narrator, but we lacked a vulnerable narrator until ‘Yolanda’:

I turned my grandmother into a bundle of lavender

I keep her at the foot of my bed I toss and turn and we do not share space well

and most mornings I wake up early enough to put her

back together before leaving for the day I am almost certain

that if I grow something with her

name in mind then she can never die

I’m wholly invested in navigating black pain, but believe to survive we also need to explore joy. Anunciacion, in my opinion, believes this as well and continues to wrestle with the idea of what joy is to them. How can I slow down and smell the roses if I also acknowledge that my kin died for the flower to live? The Way We Move Through Water is Anunciacion’s debut collection, and, if this is where they start, I can’t wait to see where they go.