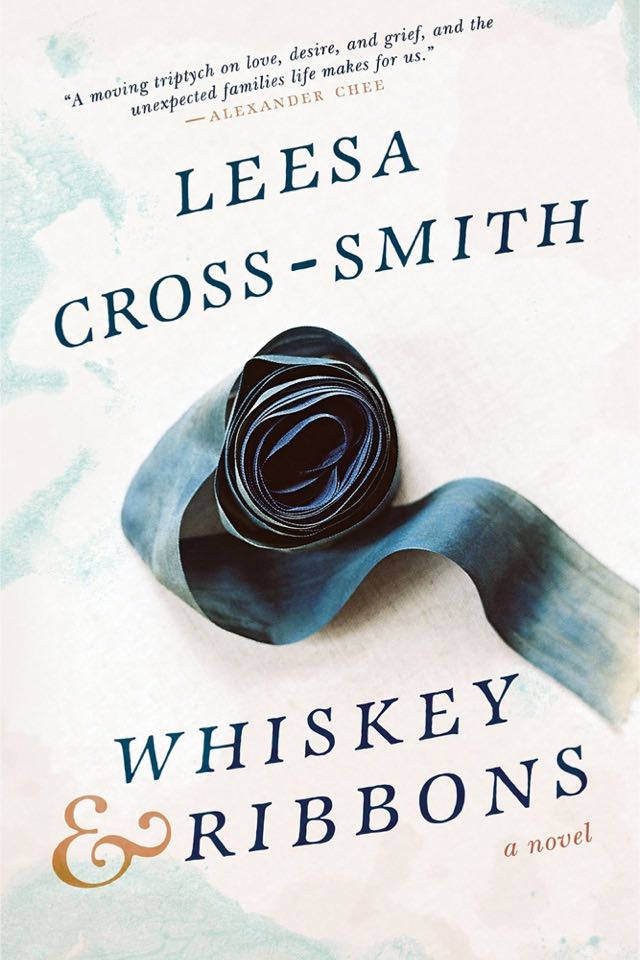

Whiskey & Ribbons

— Yael van der Wouden

It’s been a while since I read a novel that was so fully and entirely about people. I’m not sure how that happened, but thinking back to the stories I’ve lost myself in over the past twelve months they’ve all been—in one way or another—about people being defiantly unlike people. A lot of absurdity, a lot of magical realism. A lot of getting to close the book, put it on the table and say, Well that was strange and will never happen to me. What a relief.

Reading Leesa Cross-Smith’s Whiskey & Ribbons in contrast to that was like being sat in front of a mirror after not having seen your own reflection in years: wondrous and confrontational and sad all at once. First of all, let me say there’s also no such thing as closing the book and putting it on the table

with this novel—it will not allow it. I believe I read it in three sittings: on the train, then on the couch, and after a quick lunch break I returned to that couch and that is where I finished it. As I’m writing this I’m still in that strange limbo world that I know all of you are familiar with: where you’ve reluctantly continued on with your life but keep thinking, Oh I can’t wait to go back to the book before remembering you can’t, the story has reached a close.

Whiskey & Ribbons is about grief as a form of love, and how love in its own right can often be a grieving thing. The story starts like this: Eamon, a police officer, is killed while on duty. His wife, Evangeline, is nine-months pregnant when it happens and is still coming out of the delirium of grief when giving birth to their son, Noah. And into this mix of loss and life hurtling onwards steps Dalton, Eamon’s brother, grieving himself and working through that by becoming Evi’s lifeline.

The story is told in triptychs, each chapter taking turns in delving into the three characters’ narrative arc. The consistent and repetitive nature of whose voices we as readers get to hear—Evi, Eamon, Dalton, Evi, Eamon, Dalton—works in brilliant contrast with how non-linear and meandering the story actually is. We know what character is going to speak when, but we never know where they will take us: to their childhood, to their present, to a memory they have of something that has nothing to do with the main plot. In a clever way, this format seems to reflect how each of them experience much of their lives—an arbitrary structure holding together the overwhelming multiplicity of histories, all of them woven together.

But what I liked best about reading this novel, this people novel, is how genuine and true it was to each character it allowed to come forward—to have their say. Evangeline is a dancer and so her sections read like a dance at times, in particular the scenes where she and Dalton move through the house after getting snowed in: they sit, they stand, they walk, they talk—there’s a musical element to it that reads like how a dancer might see the world in 8-counts. In contrast, Eamon’s internal world is also much like him: bright and honest and aching with love for Evi. He feels everything in exclamation, is unabashed about it, which only shows more beautifully when read side-by-side with Dalton’s voice. Dalton, who is quieter and solid at times, scattered at others, is sure and unsure of his own love – of the love others have for him.

And by making these characters so genuine and full, their desires—their losses and their grief—all become magnified as the story continues. Reading of Evi’s want on the first page is a wholly different experience when you read of that very same desire, in the last chapter. In a similar way, the ache of Eamon’s death is a different thing by the end—you, as a reader, are welcomed into the midst of that grief. Are allowed to experience it as the numbing, loving, all-encompassing thing it can often be. That, too, is another element of Cross-Smith’s writing that rings so very true: the way grief tilts a world, one’s understanding of what’s there, what isn’t. The way the brain needs to catch up to a great loss, how you end up asking yourself: wait, why aren’t they here?, truly forgetting for a moment what death is, what it means.

When I was halfway through the story a friend asked me what I was reading, and I was too busy reading—too enamored by reading—to reply properly. But I did end up babbling something that I still stand by: that the way this book reflects on love found in grief surprises in the way a tree grown into a fence is surprising—that the movement was not away from but rather toward, rather to intertwine.

Best read: without putting it down, or putting it down only when absolutely necessary; when warm, perhaps in bed or near the heater; when a season is changing; when you want to be reminded that loss is never the lonely thing it is made out to be.